Desalination: The Miracle and The Wall

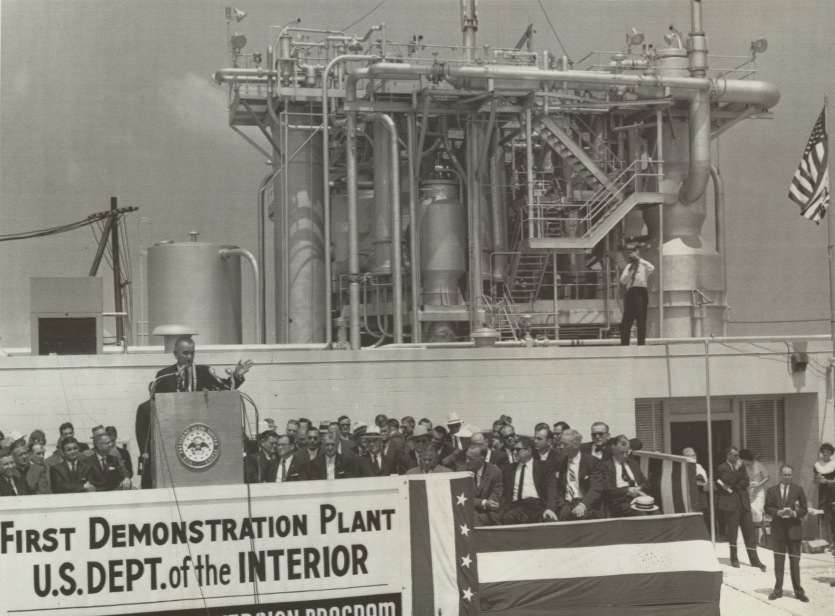

On June 21, 1961, in a dusty small town in Texas, about 60 miles south of Houston, President John F. Kennedy stepped up to the podium to make a speech before the assembled throngs of people below. Or rather, his aides did. The ongoing fallout from the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and tensions in Berlin demanded his presence in Washington, so he instead gave the speech through a telephone call. The event, however, was deemed of sufficient importance that Vice-President Lyndon Johnson was in attendance.

Behind the stage was a dense, tangled maze of stainless steel piping, tanks, and stairways—the fruits of labor of countless scientists, engineers, and government officials who had been toiling relentlessly for years. And thanks to their efforts, the project had been completed at breakneck speed. Kennedy’s speech was to commemorate the opening of the facility, and the geopolitical situation did not temper his enthusiasm or his grandiloquence.

“Today,” he said, “was an important step towards securing one of man’s oldest dreams.” He went on to declare that he could not think of a cause that was more important “to people around the globe”, and that this was “a work that in many ways is more important than any other scientific enterprise in which this country is now engaged.”

With this effusive praise, Kennedy was not talking about space exploration, the Apollo program or the goal of landing a man on the moon, which he had announced a month earlier in an address to Congress. He was talking about the opening of a desalination plant in Freeport, Texas—the first of its kind. Fed by belching coal boilers, it was capable of producing one million gallons of freshwater per day, providing relief to the drought-ravaged town of Freeport, as well as a nearby chemical plant owned by the Dow Chemical Company.

The practical implications were overshadowed by the symbolic ones. The 1950s were an era of unbridled optimism and the belief in the ability of science and technology to deal the finishing blow in mankind’s eternal war against poverty, disease, famine and drought. Medical advances and improved sanitation increased the average American lifespan from 53 years in 1920 to 70 years in 1960. Nuclear power promised clean, abundant electricity, with prices eventually being “too cheap to meter”. The Green Revolution made crop yields explode, cementing America’s food security. Now, it seemed that the final enemy left to overcome was drought.

In a sense, this plant represented the ultimate triumph of human ingenuity over the vicissitudes of the weather and climate. Finally, mankind would meet its basic needs in “areas in which Nature was not generous.” The deserts would literally bloom, and men and women in dry climates everywhere would be lifted into prosperity.

The starry-eyed enthusiasm didn’t last. The high spirits of the age were met with crushing economic—and political—reality. The mercurial nature of weather goes both ways, and a few years later, the rains came back to South Texas. It cost the government \$1.25— \$14.87 in 2024 dollars—to produce one thousand gallons of water, which it sold to the town of Freeport for $0.30, the going price of naturally-sourced water. Once the funds dedicated to the project ran out, Congress had no inclination to keep producing a now-abundant commodity at a loss. The plant shut down in 1969. The 1970s energy crisis, which nearly tripled the cost of oil, subsequently curtailed any incentive to build these fuel-hungry facilities.

One of Earth’s greatest ironies is that although 70% of the world’s surface is covered in water, the IPCC estimates that half of the world’s population faces serious water scarcity risks. Like the Greek mythological figure Tantalus, there’s a promise of plentiful water that frustratingly forever lies just-so-slightly out of reach.

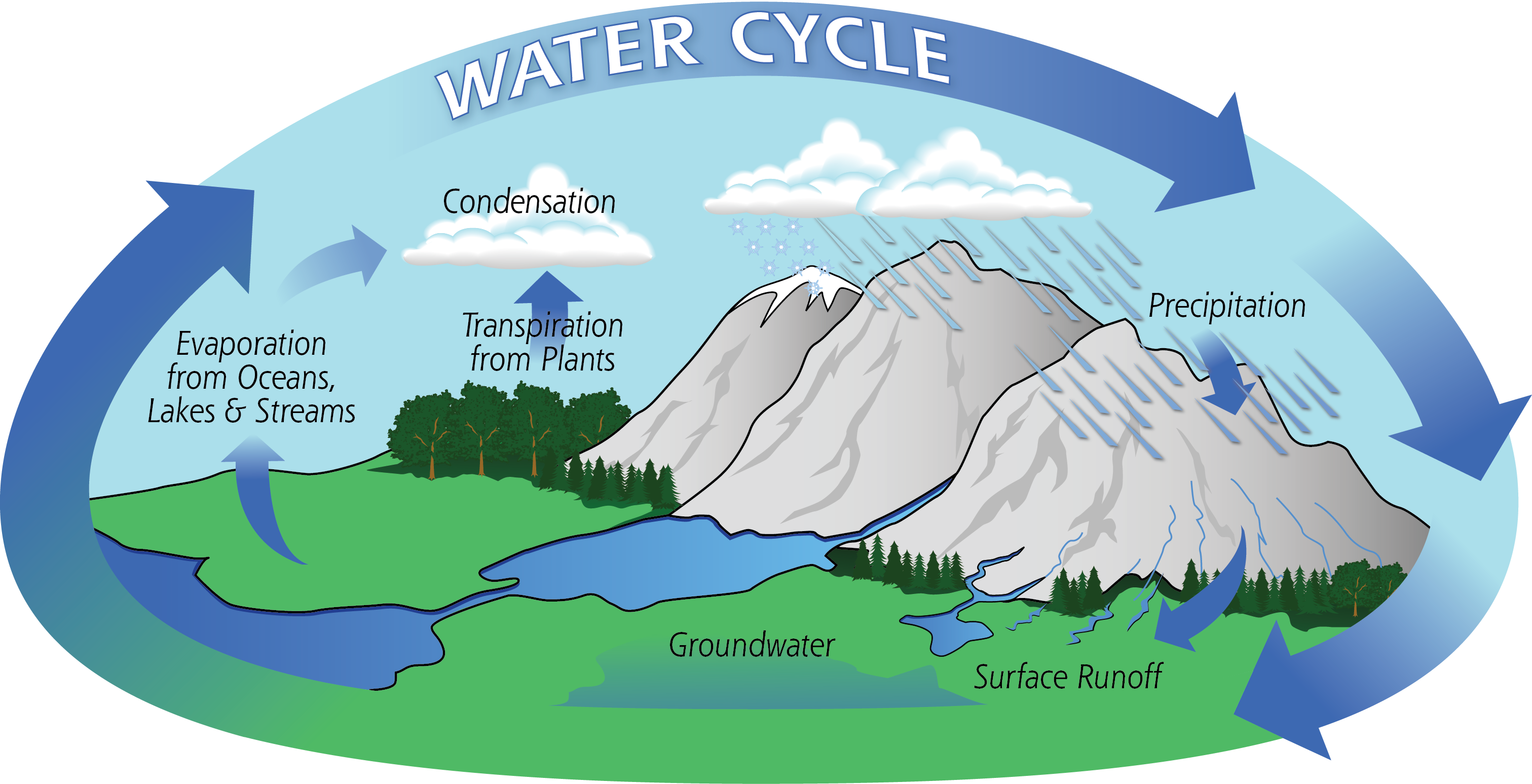

Most water used by humans comes from the hydrological cycle. In the warm ocean regions, water evaporates and thanks to atmospheric circulation, moves around the globe. Eventually, it condenses into clouds and falls out of the sky as precipitation. Depending on where it lands, the water can accumulate in ice caps or glaciers, flow back into the oceans through rivers, or be stored in lakes or aquifers. Although the water eventually makes its way back to the oceans, all these serve as sources of fresh water for humans, plants, and animals.

But the availability of these resources varies greatly with geographic region. There’s no guarantee that your land will be pocked by lakes, that rivers will run free, or that the aquifer will provide useful quantities of water. If—or when—the need arises, there are only two ways to increase the available water supply: water reuse and desalination. If you didn’t have water to begin with, the first option is not very helpful!

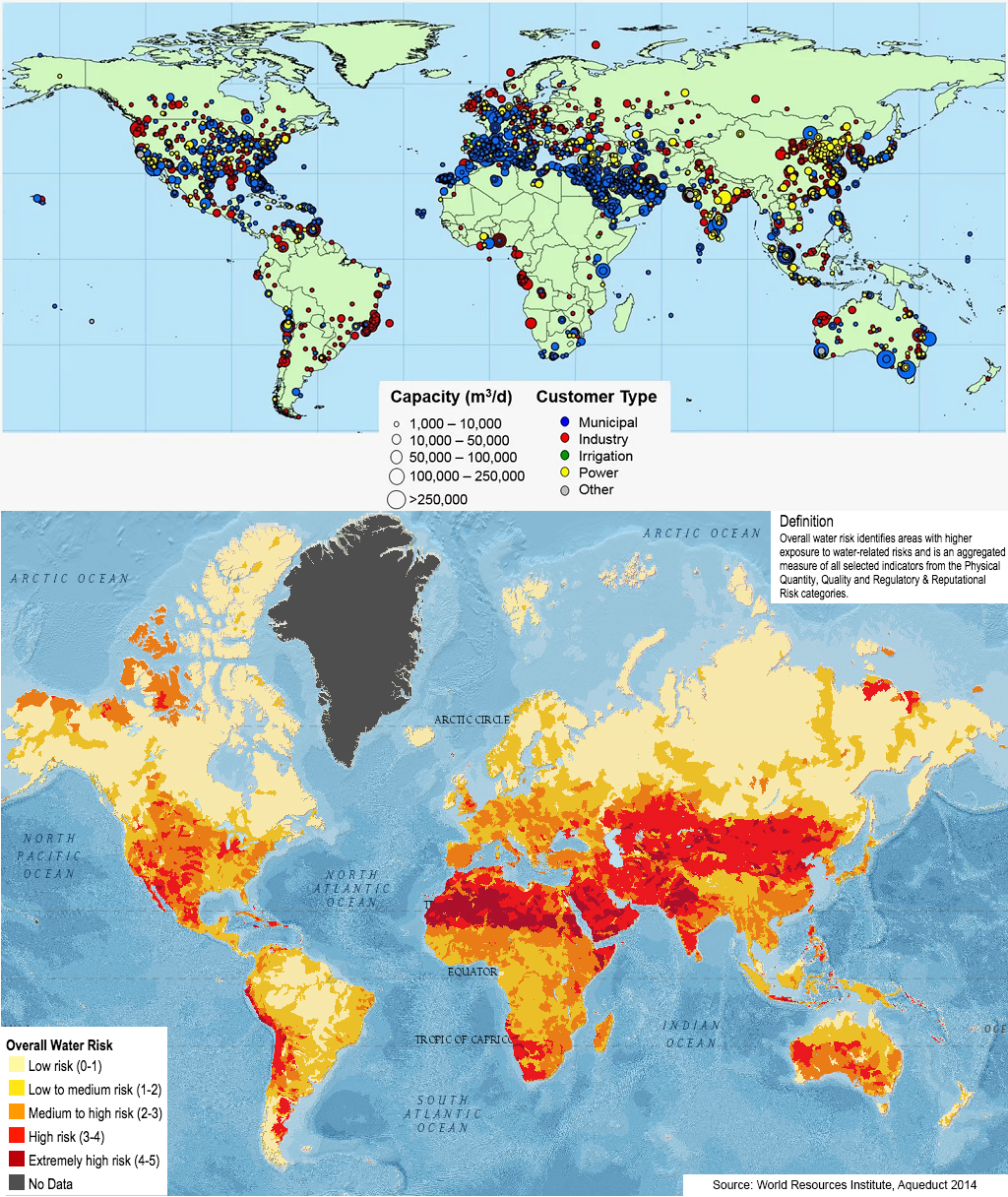

That’s why access to water has historically been the key determinant of the evolution of human settlements. Today, 40% of the world’s population lives within 100 km of a coast, and 50% live within 3 km of a freshwater source (only 10% live more than 10 km away from one).

It’s not just a question of having enough to drink and eat, either. A reliable supply of water is crucial to economic development. Water, as part of the water-energy nexus, plays a crucial role in energy production—thermal power plants require large amounts of freshwater to use as a coolant1, and large amounts of water are needed in the production of solar panels and wind turbines. Nearly all industrial activity uses water in some way as a solvent, reactant, and/or heat transfer fluid. Even beyond the humanitarian angle of crop failures and drought, a nation that struggles to meet its water needs is a nation doomed to economic stagnation.

Climate change will make all these issues worse. While the total amount of precipitation won’t meaningfully change, the distribution of rainfall, snowmelt and river flows will shift. Weather events will become more extreme, variable and less predictable. As the soil dries up, it becomes less capable of absorbing water, making the less-frequent-but-more intense periods of rain unable to replenish aquifers. Droughts will increase in frequency and severity. When combined with other issues, such as pollution and eutrophication, potentially billions of people could experience water shortages by the 2050s.

Seawater desalination could potentially help alleviate these issues. Historically, it’s been an incredibly energy-intensive process, resulting in high costs as well as a high environmental impact, limiting its potential usefulness. But could that be improved? How much better could it get, and would more R&D efforts get us there?

A brief history of desalination

The largest, most expensive and complex part of a chemical plant is typically not, as is popularly believed, the reactors that combine chemicals to produce new, more valuable ones, but rather the steps that split a mixture of chemicals into distinct streams of a specified purity. The techniques for “de-mixing” are cumulatively known as separation processes. In many respects, this is chemical engineering’s most fundamental discipline.

Fortunately, desalination—the art of separating salt and water—is a relatively simple process. Humans have done it for millennia—Aristotle noted that “salt water, when it turns into vapor, becomes sweet and the vapor does not form salt water again when it condenses”. But this approach requires enormous amounts of heat, and as such desalination was never feasible on a large scale prior to the Industrial Revolution and the concomitant availability of coal and other fossil fuels.

The idea was revisited at that time, mostly in military contexts. Armies were not as concerned about efficiency and economic viability as they were with the logistical convenience of being able to produce fresh water for their troops in-situ.

Research into economic desalination accelerated after WWII, particularly in the United States. In the 1950s, the southern US underwent a severe drought—the worst in the nation’s history—and there was significant political pressure to find a solution. This is when some began to consider the possibility of large-scale, economic distillation of seawater as a source of water security and a bulwark against the fitful caprices of rain. Congress passed the Saline Water Conversion Act in 1952, which led to the creation of the Office of Saline Water in 1955 and its eventual merging with the Office of Water Resources Research in 1974.

The first desalination plants, like the one in Freeport, used multi-stage flash distillation (MSF) to distill the water. The idea is quite simple: boil the water and collect it, leaving the salt behind. A series of heat exchangers captures the heat from the condensing vapor to boil a subsequent batch of water, minimizing energy waste.

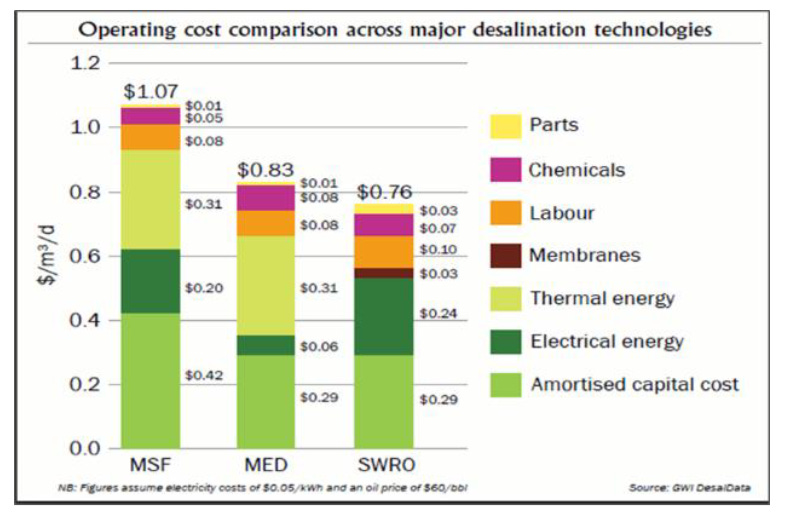

This approach is effective at producing drinkable water in large quantities, but there’s a big downside. It is horrifically energy intensive. No matter how you slice it, boiling water takes a lot of energy, and not all of it can be recuperated. A typical MSF plant achieves a Specific Energy Consumption (SEC) of 23-27 kWh per cubic meter of water. At an electricity price of 8 cents per kWh, roughly the average in the US for industrial customers, it would cost over $2.00 to produce a cubic meter (1000 L) of water. But in comparison, the average price of water in the USA is only $0.40 per cubic meter (although it is strongly location-dependent). And that’s before labor, maintenance, distribution, capital amortization and taxes are factored in, which would, in general, double or triple the cost.

Paying over 10x the average price for your water is quite literally a tough sell. In many cases, it’s cheaper to simply ship the water in from elsewhere. It’s unsurprising, then, that MSF desalination never saw the widespread adoption that Kennedy and Johnson would have liked. And in the 1970s, funding for desalination dried up—pun unintended2. Desalination was a niche technology of last resort, only used in locations that had access to abundant energy but for whatever reason had no other options for sourcing water.

Enter reverse osmosis

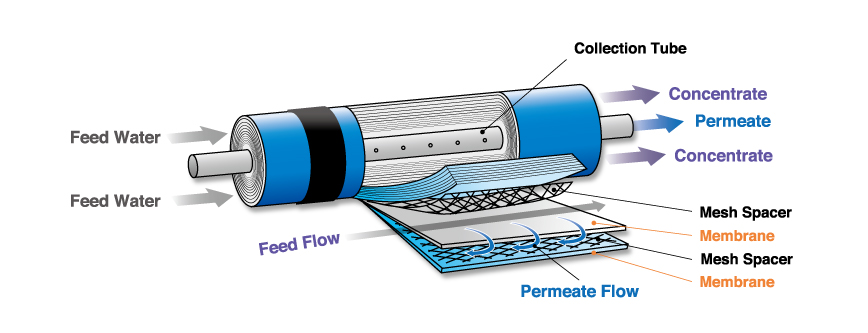

The ultimate success of desalination can be credited to Sidney Loeb and Srinivasa Sourirajan, who co-invented the first practical reverse-osmosis membrane, a much more energy efficient technology. While the concept of a salt-removing filter was not novel, their membrane was the first that was relatively inexpensive, durable, and had a sufficiently high water throughput to be economically viable. The trick was using a two-layer approach: a thin, tightly-woven layer on top provided the salt filtering capability, while a thicker but more porous layer on the bottom provided the strength needed to withstand the required pressures. Today, practically all commercial reverse osmosis membranes still employ the same concept.

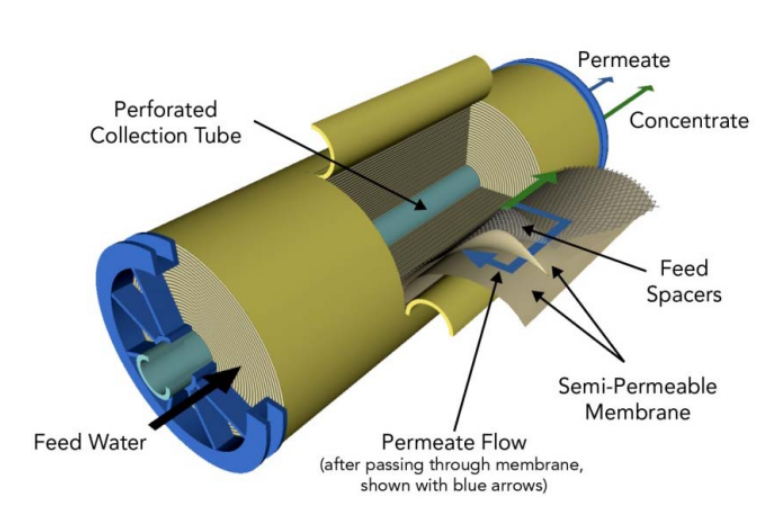

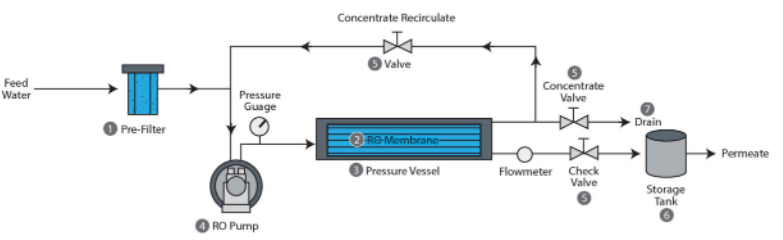

Reverse osmosis is achieved by pushing the water across a semi-permeable membrane using a difference in pressure. In a typical setup, the water, once filtered for large debris like branches, rocks, and algae, is fed through a pump and through a spiral-wound tube. The walls of this tube are made of a membrane with tiny pores that allow water molecules to pass through but block larger salt molecules.

At first glance, this just seems to be like any other kind of filtering process. What’s the big deal? I use a “semi-permeable membrane” to separate the coffee grounds from my morning brew every day. Why does this have a fancy name attached to it?

The key distinction between reverse osmosis and a filtering system is the spontaneity of the process. A fluid filled with undesirable particles will naturally flow through a sieve in the absence of a minimal driving force. Increasing the pressure will increase the flow rate through the filter, but it’s not a requirement. Using my coffee as an example, if I was fine with waiting forever, eventually all of the coffee would trickle down through the filter—except a small amount retained due to surface tension—resulting in almost no energy expenditure.

Reverse osmosis, on the other hand, is not spontaneous. If you passively place a concentrated salt solution next to a reverse osmosis membrane without applying a driving force, nothing will happen. The water will never migrate across the membrane on its own. To do so, it needs to fight against the osmotic pressure generated by the difference in salt concentration across the membrane—hence the term “reverse osmosis”. The amount of pressure needed depends on the membrane permeability as well as the concentration of salt in the seawater.

There are many advantages to a pressure-driven process over a temperature-driven one. Pressure is a lot less leaky than temperature, leading to better energy efficiencies, and corrosion is much more manageable at lower temperatures. Phase changes (boiling or condensing) require large amounts of energy to be transferred to and from the water, requiring the use of a myriad of heat exchangers, boilers and utility lines, all plumbed together in a complex manner to achieve acceptable efficiencies. Pressurizing a liquid is very easy: just pump it. Not only are reverse osmosis plants more energy-efficient, they are more capital-efficient as well as they are simpler to design and build.

The pressure requirements are where the bulk of the energy consumption for desalination come from. But how much of that is actually needed? Using advanced physics and material science, would it be possible to invent some kind of magical filter that would let water pass through really easily, but keep the salt out, or to invent some new technique that would be able to sidestep the need for high pressure? Wouldn’t that allow us to have cheap and easy freshwater anywhere in the world, and thus eliminate the threat of thirst for humankind once and for all?

The theoretical energy of unmixing

So how much energy is actually needed to separate a mixture’s components from one another? What is, so to speak, the theoretical minimum, and why does it exist?

First, let’s start by defining what we mean by “mixture”. We are referring to a fluid consisting of multiple components (e.g. water, salt, sugar, ethanol) but which has homogenous physical properties throughout the fluid. By contrast, a fluid with heterogeneous physical properties (e.g. water with sand and sticks in it) is called a suspension. This is an informal definition—a more rigorous one would have to address some additional subtleties3—but it is good enough for our purposes.

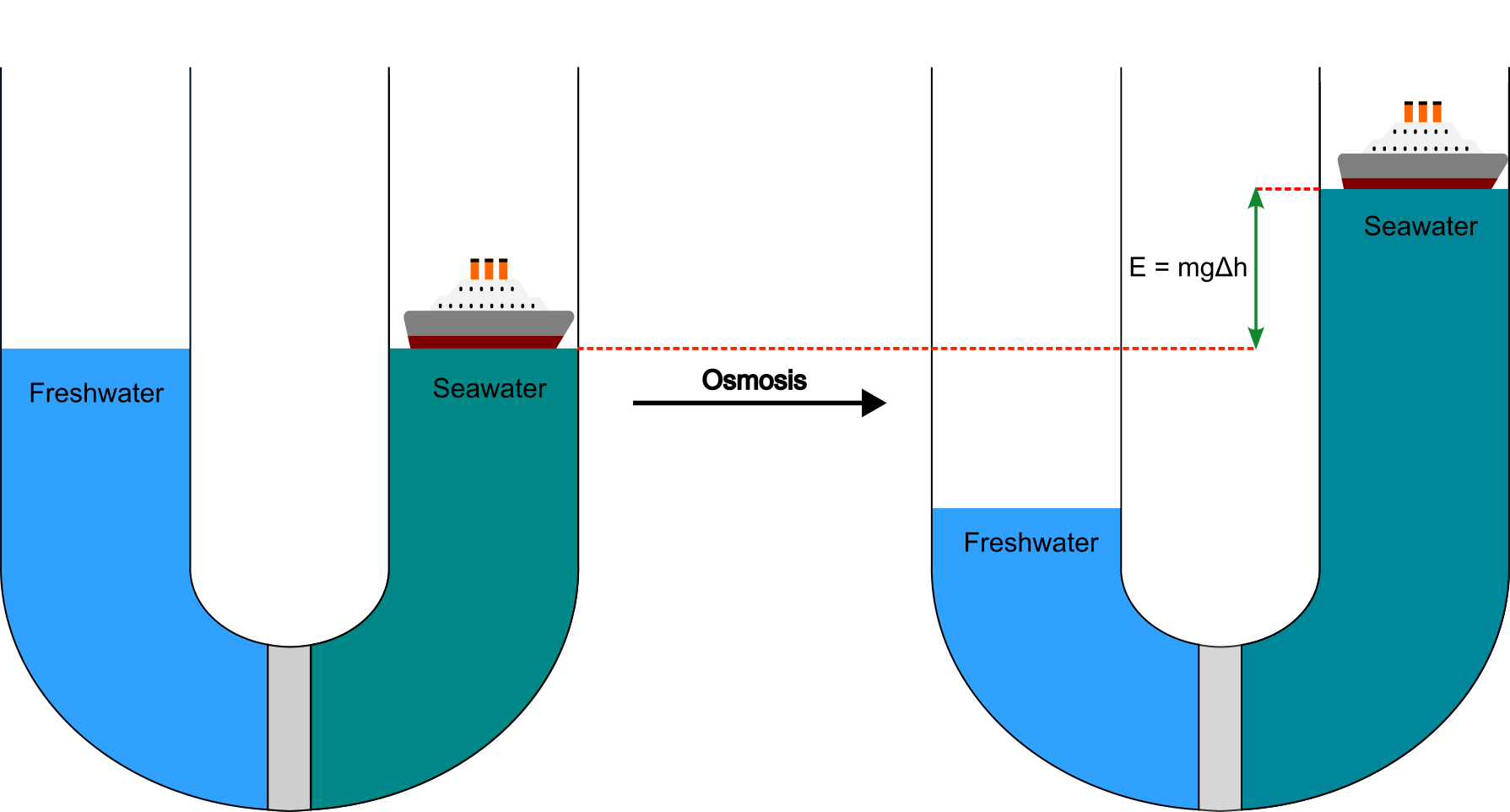

Let’s imagine we have a very large U-shaped tube with a semi-permeable membrane separating two compartments, with freshwater on one side and seawater on the other. Initially, the water is at the same level on both sides. The difference in osmotic pressure draws the water from the freshwater side to dilute the salt. This is a common high school experiment, but it often overlooks an important observation: a simple difference in solute concentration between two solutions can result in the bulk movement of a weight—in other words, performing work! If there was a ship in the seawater compartment, we could thus exploit the concentration difference to lift the ship up against the force of gravity.

Where does this energy come from? Unfortunately, the complete answer—involving the concept of chemical potential—is somewhat abstract4, but the gist is that there is potential energy inherent in a difference in concentration, much like how a difference in height or a difference in temperature can be exploited to produce usable energy.

It follows that since reducing a concentration difference can produce energy, returning to the initial concentrations (via e.g. some purification process) must, at a minimum, require the same amount of energy. How much energy? The exact amount is known as the Gibbs free energy of mixing (or separation, when considering the opposite process).

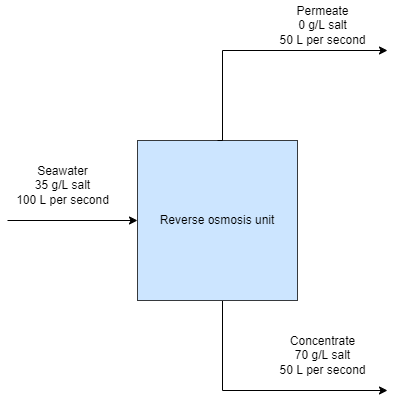

Next, let’s examine a hypothetical water desalination system, without any reference to a specific technology or approach. At a high level, any such system would have to look like the block diagram below:

Although the goal is to extract the water from the incoming stream, we can’t extract all of the water, or there would be nothing to carry the salt out of the system. Therefore we have one stream—the seawater—going into the unit and two streams exiting it: a stream of desalinated water called the permeate, and a stream of concentrated saltwater called the concentrate, or brine. The ratio of the flow rate of the fresh water stream to the inlet stream is called the recovery ratio, and it is the fraction of seawater intake that is converted into freshwater. $$ R_w = \frac{\text{freshwater flow rate}}{\text{feed flow rate}} $$ The recovery ratio roughly captures an important tradeoff between capital expenditures and operating expenditures. A higher recovery rate means a smaller feed flow rate is needed to achieve a given freshwater production rate, resulting in smaller pipes and equipment, but also means more energy consumption, as we will see shortly. Desalination plants commonly use a recovery ratio of 50%, but the exact value at a specific facility depends on the particularities of its operation.

A high recovery ratio results in a more concentrated brine. Intuitively, this should result in more energy required to extract the water since a more concentrated brine will have a higher osmotic pressure.

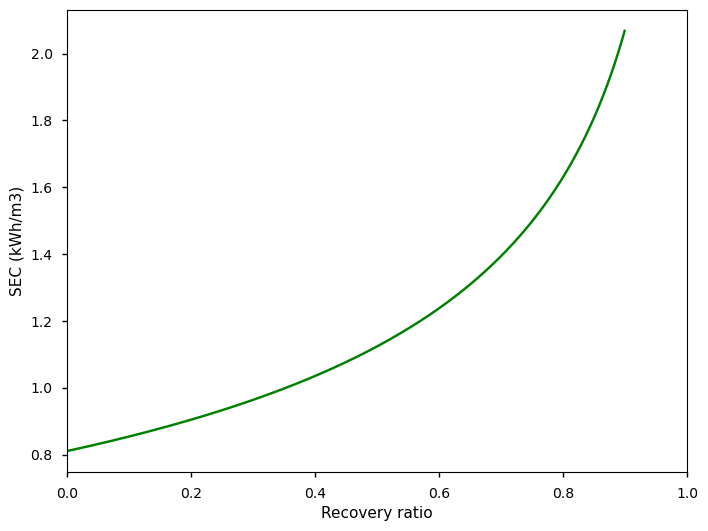

When we convert the Gibbs free energy of separation to a per-unit-volume-of-water basis, we obtain what’s known as the Specific Energy Consumption (SEC): $$ SEC = \frac{\Delta G_{sep}}{\text{Volume of water produced}} $$ It turns out that for seawater, due to the fundamental thermodynamic and physical principles, the SEC only depends on the recovery ratio5.

For a typical seawater salt concentration of 35 g/L, and assuming a recovery ratio of 50%, we get a SEC of ~1.1 kWh/m3 of water. No matter the separation technique, it is thermodynamically impossible to desalinate seawater using less energy6.

As the water gets transferred across the membrane, the brine side becomes more concentrated with salt, which leads to a corresponding increase in the osmotic pressure. This leads to a sharp increase in the SEC above a recovery ratio of ~0.8.

As an illustrative example, think of wringing a wet towel: when the towel is soaked, a gentle twist is enough to have the water come gushing out. As the towel dries out, however, it becomes progressively harder and harder to extract more water out of it, requiring more and more force to be applied until eventually no more will come out.

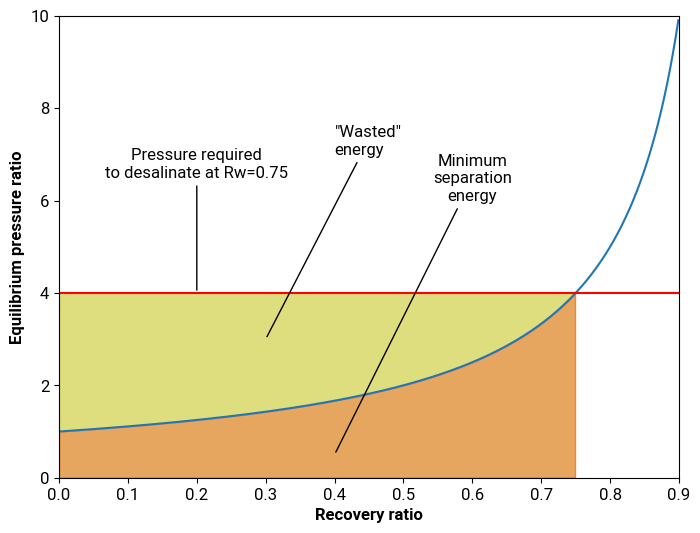

Now, imagine if you could only apply one level of torque to wring the towel, instead of gradually ramping up the torque. (Perhaps you are programming a robot to do it, and the actuators only have an on/off setting.) In that case, you would have to apply a force that would get the towel to the level of “dryness” that you want to achieve, even if this amount of force is initially overkill when the towel is very wet.

The same reasoning applies to RO membranes. To achieve perfect efficiency we would need to continuously increase the pressure along the membrane flow path proportionately to the increase in salt concentration. This is, to say the least, an impractical proposition. The best we could do would be to maintain the pressure constant over the length of the membrane. In order to achieve a desired recovery ratio, the pressure applied to the membrane needs to be at least equal to the final osmotic pressure of the brine.

Plotting the pressure vs. water recovery on a graph, we get a relative sense of the “wasted” energy vs. the “required” energy.

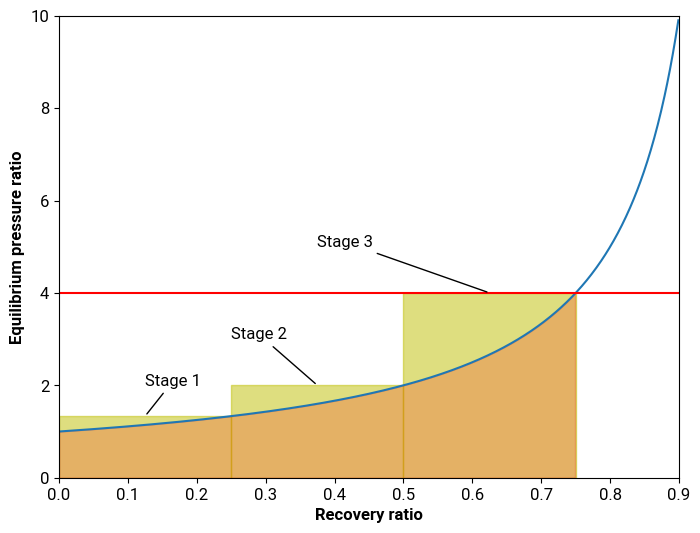

This relationship is, in a sense, the “rocket equation” of desalination, because there’s very few ways to actually improve it. The equilibrium curve is a fundamental property of the fluid, and so there’s no technological solution that can change it. There’s only two things we can do: change the target recovery ratio, or, just like with rockets, add staging by changing the number of “steps” we take to reach the final recovery fraction.

Instead of having a single large reverse osmosis unit, we can place multiple smaller units in series, with pumps in between each unit to boost the pressure to the new equilibrium pressure. However, this increases design complexity and capital and maintenance costs, so there’s no free lunch: at some point the additional expenses will exceed any savings from efficiency gains.

The miracle…

The energy intensity of desalination has been one of the primary reasons why it hasn’t seen more widespread adoption. (Other issues such as the environmental consequences of brine discharge also dampen the prospects for widespread deployment but are not quite as salient.)

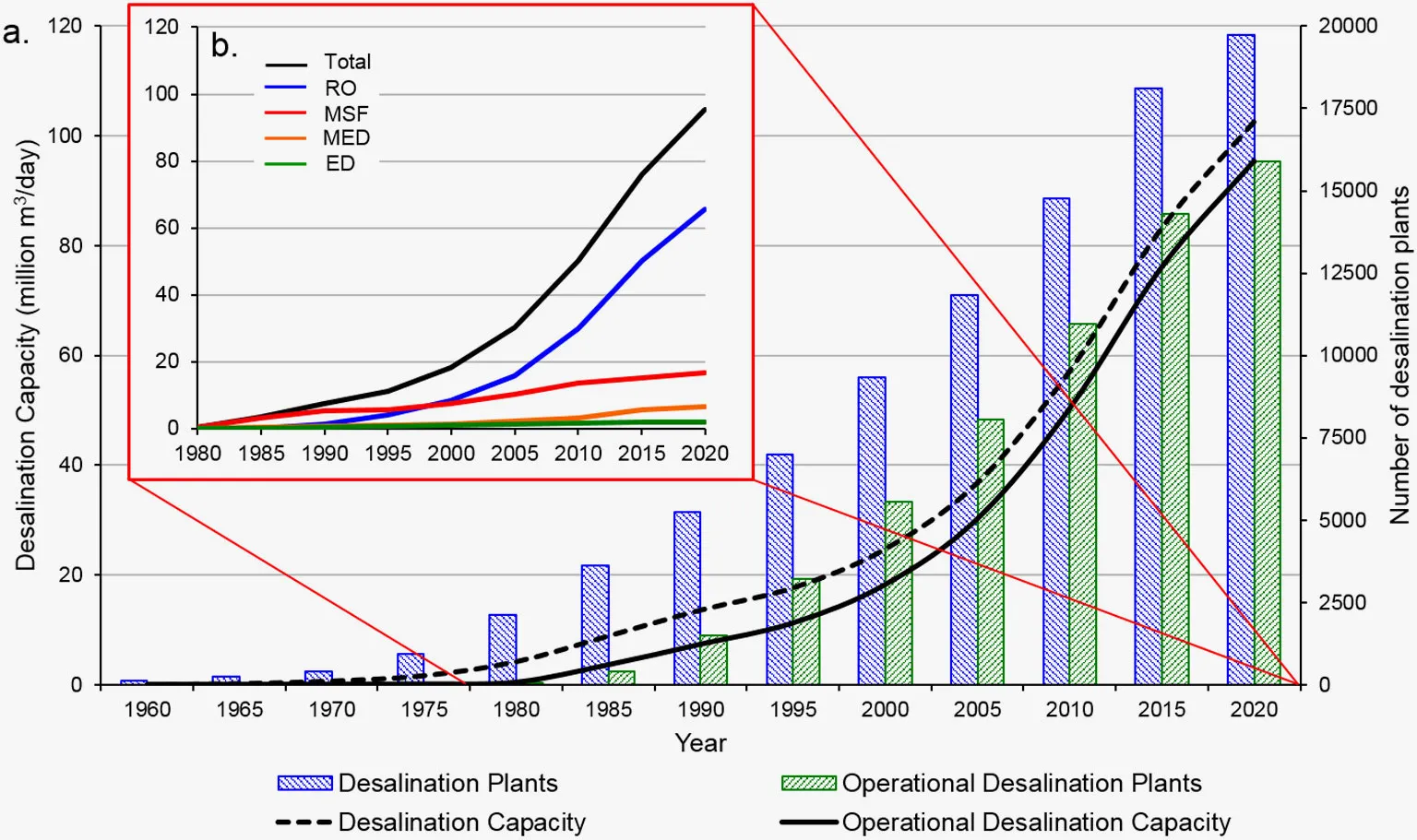

Returning to Loeb and Sourirajan, their invention kicked off a flurry of innovation and continued improvements that persisted for decades. Modern membranes have since come a very long way, with an almost 90% reduction in energy consumption since the first commercial versions. Today, reverse osmosis membrane technology has virtually completely displaced MSF and become the standard for desalination plants around the world.

Putting the prior numbers into context, membranes today can now consistently achieve a thermodynamic efficiency of 80-90%, which means they only require about 25% more energy than what’s physically possible. A single-stage RO process with 50% recovery requires ~1.6 kWh/m3 of energy in theory, and the best single-stage commercial RO systems available today use about 2 kWh/m3. The total energy consumption is now consistently less than 5 kWh/m3 and is approaching 3 kWh/m3 for the most efficient plants.

What does that number actually mean? As an illustrative example, Canada consumed about 4.86 billion cubic meters of potable water in 2019. If all of that water came from desalination, it would represent an additional 9.7 TWh of electricity per year. Canada’s annual electricity production is about 632 TWh, so desalination would roughly represent 1.5% of total energy consumption. By comparison, if MSF desalination was used instead, it would require over 120 TWh to supply all of Canada’s water, or nearly 20% of all energy consumption just to produce water! Keep in mind that Canada is one of the most energy intensive countries per capita as well as one of the world’s most developed economies.

Of course, the reverse osmosis step is but one of several needed to obtain drinkable water, but it is the most energy-intensive by far. And modern, large-scale, state-of-the-art facilities are extremely efficient. The Sorek 1 plant in Israel, which opened in 2013, consumes about 740 GWh annually and has a capacity of 640,000 m3/day, enough water for 1.5 million people. This corresponds to a total energy consumption of 3.3 kWh/m3. So on top of the ~2.0 kWh/m3 needed for reverse osmosis, they only need an additional 1.3 kWh/m3 for pre-filtration, post-treatment, intake, discharge, pressure losses, and the works. It is, frankly, incredible that we’re able to get it this low.

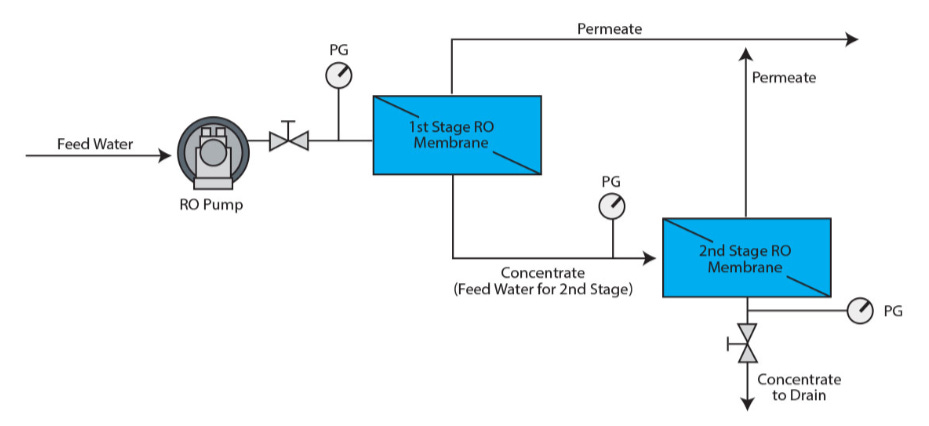

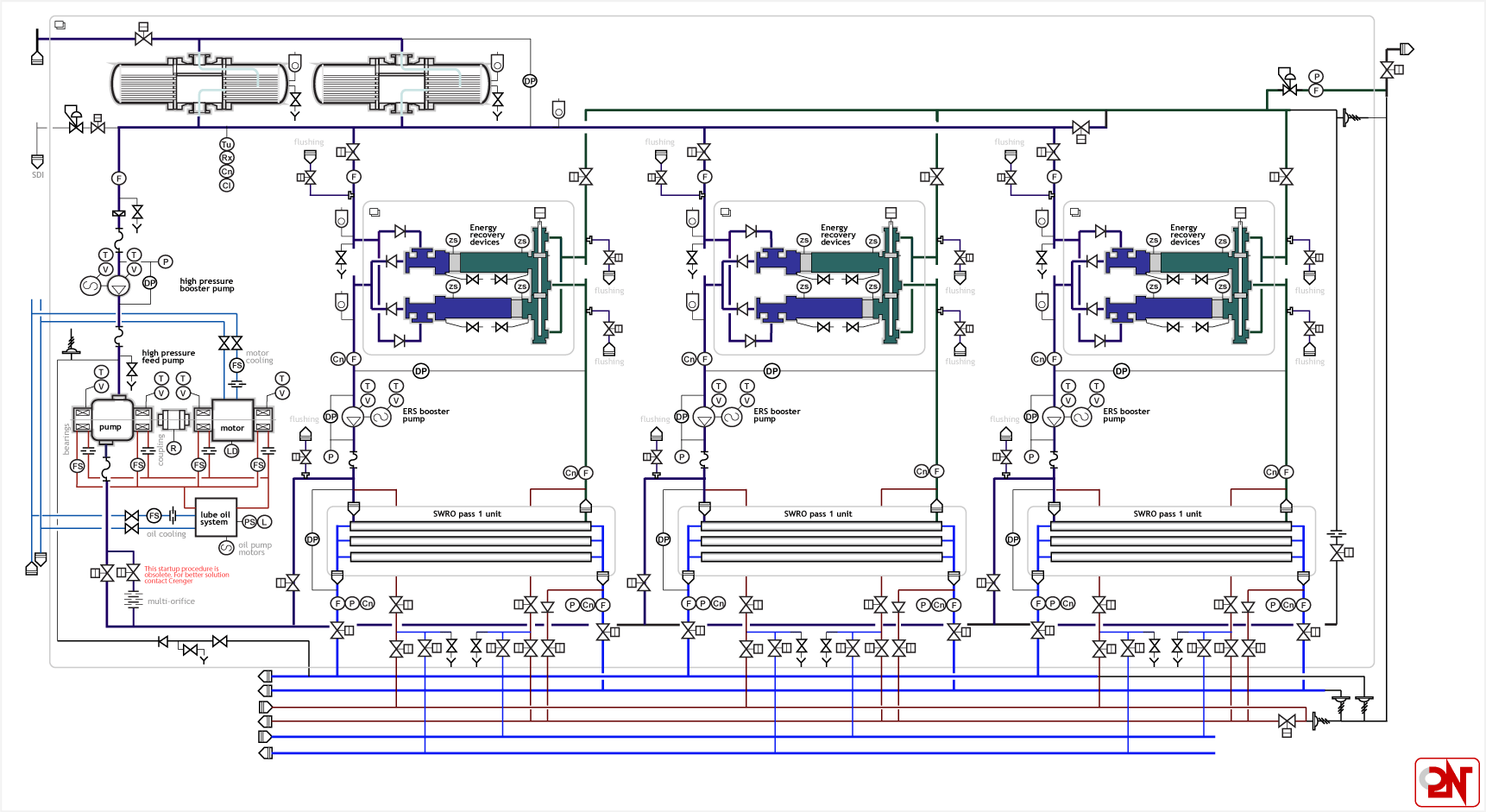

These high-efficiency systems are unsurprisingly much more complex than the simple diagrams previously shown, with parallelized pipelines, circulation loops, heat exchangers, cleaning systems, and energy recovery devices. A typical piping and instrumentation diagram for a reverse osmosis system will look like a dense and inscrutable maze of symbols and lines.

One common technique to improve the energy efficiency is to reuse as much of the pressure energy from the brine as possible, since it exits at a high pressure but no longer has any need to be pressurized. Pressure exchangers are nifty devices that can do this with very high efficiency.

All of this is only a fraction of the plant’s functionality! Depending on the quality of the membrane and permeate, sometimes an additional pass is needed, called Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis (BWRO). In addition, the plant requires systems for pre-filtering the water and handling all the sludge that gets separated out, a post-treatment system that adds minerals, disinfects and adjusts the pH, anti-scaling systems that flush out mineral deposits from the RO membranes to prevent fouling, and more.

Today, about 1% of the world’s drinking water is provided through desalination. This is likely going to rise as water security issues become more pressing, particularly in the Middle-East. The amount of desalination plants being built is rising, thanks to the dropping costs, and has now reached over 100,000,000 cubic meters per day.

The tender for the Sorek 2 plant, which will be even larger and more cost-effective than Sorek 1, is priced at $0.45/m3. This is a very impressively low number. It’s low enough to affordable to all but the most impoverished households for their daily needs, year-round. This is the miracle of desalination.

…And the wall

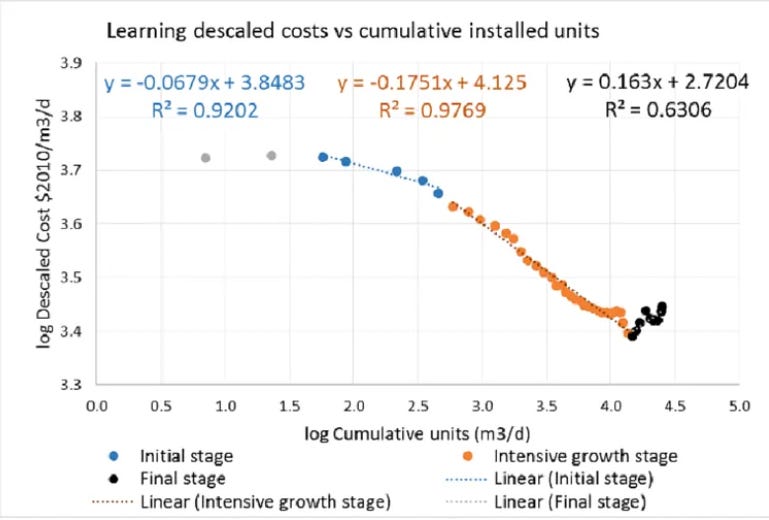

Despite this astonishing progress, at the same time, there’s little evidence of an “exponential” adoption curve—if anything, growth is slowing down slightly, as the lowest-hanging fruits get picked. Why?

There’s a common misconception that droughts are acute, short periods of no rainfall. While this can be the case, in reality they are often prolonged periods of reduced rainfall that can last years. And while a plant can be built, commissioned, and run profitably for a few years over the duration of a long drought, these plants are typically planned and designed to operate over timescales of 20+ years. And just like what happened with Freeport, this makes the economic projections of these ventures fraught with uncertainty. Desalination is a long-term solution, and thus the political and economic incentives also need to be long-term ones.

$0.45/m3 is very cheap, but it’s still significantly more expensive than what’s typically paid by agriculture, which is by far the largest consumer of freshwater. For comparison, a recent Berkeley study estimated the median value of irrigation water for wheat to be $0.05 per m3. In many cases, farmers don’t even pay the costs for distribution or delivery!

Let’s put this into perspective. Growing wheat requires approximately an acre-foot of water per acre of wheat. Data from the USDA indicates that an acre yields on average 45 bushels of wheat and that the total selling price is approximately \$350. If the water was purchased from Sorek 2, then it would cost at least \$550 per acre to water the crops, more than doubling the minimum production cost of wheat.

To truly usher in an era of abundance and unlock affordable water and water-based economic activities for everyone, we need to eventually reduce desalination costs even further, ideally by 75% or more. Can it be done?

Electricity costs account for a majority of the operating costs of a typical desalination facility. But the thermodynamic limit places a fundamental restriction on future cost savings. Desalination is not just at a local maximum, it’s approaching the global maximum: energy consumption can only improve by 25% with a physically perfect separation technology. This is the wall.

Diminishing returns are already starting to kick in: new R&D initiatives are met with disappointing results while membrane performance stagnates. As this sobering 2020 review notes, research efforts have been stunted by a “universal insignificance of novel materials in further enhancing the energy efficiency of desalination”.

Other cost drivers are much smaller. Reducing costs elsewhere will be a multifaceted, arduous, and mostly incremental effort—for instance, completely eliminating maintenance would only result in a 7% overall reduction in OPEX.

As a result, despite a historical learning rate of 12% that’s led to dramatic cost reductions, desalination learning rates have sputtered out to near-zero in the past decade:

…a trend break observed over the last 10 years mirrors an exhaustion of the potential for technical improvements, as well as an increasing complexity and nonlinearity of the factors influencing the [desalination] systems’ cost.

Recent price reductions have predominantly come from economies of scale: building larger and larger facilities which can take advantage of scaling laws and shared infrastructure. The scale of the aforementioned Sorek 2 plant, for example, is staggering: 672,000 cubic meters of tap water per day. That’s a torrent large enough to fill a standard 20-foot shipping container every 5 seconds, nonstop, every single minute of the year.

But this, too, has its limits. With larger scales comes larger capital requirements, making project finance more difficult, especially for countries with limited access to credit. The other issue is one of logistics: for its weight, water isn’t very valuable, meaning that distribution costs are a significant portion of the final price paid by the consumer. This works against excessive centralization of freshwater production: when demand from nearby population centers is met and the water must be piped further away, the additional distribution costs will eventually exceed the cost savings from the larger production scales. For this reason, water treatment infrastructure has a large degree of decentralization.

When all of this is taken into account, this means that desalination has reached its endgame. While there are still small improvements to be made here and there, there’s no silver bullet to making it dramatically cheaper, and likely no path to ever reducing costs to make it viable for large-scale agriculture of thirsty crops. The dreams of making deserts bloom remain just that—literal pipe dreams.

Where do we go from here?

All this isn’t a reason to doom and gloom. Just because desalination isn’t becoming more energy efficient doesn’t mean that it can’t become more economic.

Instead of focusing on the process itself, we can look for ways to reduce the cost of the inputs: either the cost of electricity or the capital costs.

For example, with an average levelized cost of electricity from solar at 3 cents per kWh in the US, and projected to drop even more in the coming years, there’s a case to be made that desalination facilities coupled with solar power could be a cost-effective way of using excess power output. The product, water, doesn’t spoil and is relatively easy to store and transport. In fact, there have been proposals to do just that at the US-Mexico border.

Membranes that are more resistant to scaling and fouling, or are more resilient to chemical treatment would also drive costs down—the pretreatment and cleaning systems can account for over 30% of a desalination plant’s capital costs while membrane replacement and treatment chemicals account for about 25% of the operating costs.

Perhaps most importantly, even unfruitful membrane research isn’t for naught. The findings and techniques of desalination will continue to spill over into adjacent disciplines, such as wastewater treatment, mineral recovery systems, and nanomaterials7.

In many ways, desalination is one of the most striking case studies of the engineer’s method: displaying its greatest strengths, but also its biggest limitations.

First, it’s a strong testament to the power of first principles reasoning and a scientifically-minded analysis. Starting from a simple thermodynamic thought experiment, something so abstract and naively simplistic that we would think it only good for ivory-tower theoreticians, we can infer a whole bunch of the design tradeoffs and limitations of desalination plants.

Second, it demonstrates how engineering can be used to improve the human condition. Stable access to water is a fundamental building block of civilization. It is necessary for life itself and feeds crops and carries away diseases like cholera and typhoid fever. It is the difference between an uninhabitable wasteland and a hotbed of human activity. Millions of people rely on desalination to ensure that they have enough water to drink, cook, clean, bathe, grow crops, and run their businesses.

Third, it shows how continuous, compounding iterative improvement can lead to astonishing advances over long periods. In the history of desalination research, there have been very few specific points that could be considered “breakthroughs”. Instead, it’s been a dogged, persistent, multi-decadal effort by many scientists and engineers to bring the cost down to the point where—under specific circumstances—desalination is now a viable, cost-effective solution to water supply issues rather than a niche, uneconomic venture wholly reliant on government subsidies.

But on the other side of the coin, the same scientific principles that have led to these tremendous improvements also show that they’re likely not going to keep up. Better designs and better technology will help—to a point. But desalination will never become the technological silver bullet some might hope for. Instead, it will remain a tool in the arsenal of policymakers and governments around the world—a very useful tool, to be sure, but one with specific strengths and weaknesses.

Historically, desalination’s fate has been intertwined with politics and economics. In the 1950s and 60s, research was reliably championed by Senator—and eventually President—Lyndon Johnson, who had grown up in the Texas Hill Country and had lived through the punishing consequences of drought firsthand. But despite this, many plants in the 1970s and 1980s were shut down, unable to justify their costs. And in 1982, the Reagan administration shuttered the Office of Water Resources Research, as part of his agenda to defund most (non-military) government science programs.

When confronted with a large, complex, and multifaceted problem without straightforward solutions, politicians have a tendency to punt the issue to “innovation”. Eventually, someone will invent a better technology with no downsides and then we can just use it!

But that playbook won’t work here. There is no big fix coming. The technology we have is what we can and must make do with. Even Israel, the poster child of what large-scale desalination can achieve, doesn’t depend on it for the majority of its water. Its success with achieving water self-sufficiency can be ascribed to a sophisticated, multi-faceted approach to water conservation, in which desalination plays only one part.

This achievement was built up over decades of trial and error, with a patient, even-handed, long-term strategy that was able to survive the ebbs and flows of electoral politics. The small wins compounded over time into stunning results, but without the spectacle of glamourous ribbon-cutting events and glitzy big expenditures, and without the psychological certainty of salvation that a big gleaming steel plant might bring.

Solutions to water insecurity exist. Desalination can poke at the boundaries and make them more tractable. But ultimately, it will require courage, political will, and constituents who won’t punish politicians who are willing to take a gamble on a long-term vision of economic and social development.

The engineering method won’t solve this for us. And it never will.

Directly using seawater as a coolant is possible, but it is not a trivial affair, and brings with it a whole host of other challenges. ↩︎

Actually, that’s not true. ↩︎

For example, what do we mean by two mixture components being “different”? This is actually an incredibly subtle argument with implications on the definition of entropy, and is known as the Gibbs paradox. ↩︎

The actual physical mechanism of osmosis is also surprisingly obscure and difficult to put into simple physical terms. ↩︎

A full derivation of this result, starting from the Gibbs free energy of mixing, can be found in Wang et al., 2020. ↩︎

Interestingly, the energy consumption doesn’t depend on the properties of water or salt at all! That’s because osmotic pressure is a colligative property. In fact, this equation would be equally valid if we replaced water and salt with two completely different compounds. ↩︎

There’s a good case to be made that membrane technologies are still in their infancy, with a plethora of potential applications awaiting now that membrane manufacturing has made its way down the learning curve. But that’s a topic for another time. ↩︎