Reflections on my time as a design team leader

During my time in undergrad, I spent a year as a design team captain. Specifically, running a team that builds and flies rockets. I also spent several years trying (and failing) to get another design team off the ground1.

I think this was quite possibly one of the most valuable experiences I could have had as a nerdy, young, somewhat immature soon-to-be-professional with questionable social skills and very little idea of what it’s like to be on the managerial side of things. It’s a big reason why I am the person I am today.

This kind of gig is pretty rare even amongst student leadership positions. The first reason is just the sheer size of the group you’re managing. The team at the time was very large—we were one of the most popular engineering clubs on campus—with over 200 members, although in practice only about 80 or so were actively contributing to one of the team’s projects. And due to the team’s flat hierarchy, I had between one to two dozen direct reports, depending on the time of year. In industry, by the time you end up managing a team of that size, you’re most likely a mid-to-late career professional with “Director” or even “VP” in your job title. It’s probably going to be many years before I end up leading that many people again, if ever.

Within my mandate, I technically had a lot of power. We did have a few stakeholders you had to occasionally answer to—university admin to make sure we weren’t blowing yourselves up, the student society to ensure we weren’t spending your money on trips to Disneyland, our sponsors to ensure you were promoting their stuff—but aside from that we had very little oversight and full authority to run the team however we wanted. I had full control of the team’s budget (around CAD60,000 in cash and over CAD200,000 if you included in-kind sponsorships) and the final word on approving purchases.

Finally, it was a position that had a balance of technical as well as non-technical work, and more importantly, it had a long-term, concrete goal that had to be delivered by the end of the year: flying a high-power sounding rocket. There was an objective metric with which to evaluate your performance: placement in a high-power rocketry competition. This made it different from other student leadership positions where success and failure were much more open-ended, and different from other academic projects whose timeframes were at most a single semester. There were also longer-term projects that would take several years to come to fruition, which needed to be juggled alongside the shorter-term concerns.

Despite how educational this experience was for me, due to the nature of the position, only a handful of people will ever get to go through it. Given that, I want to share some of my thoughts about it, a few years after the fact. Some of this is specific to the particularities of running an engineering student design team, and some of it applies more broadly to managing large teams.

Some of these takeaways will likely come off as sounding melodramatic or self-important, but if it helps someone out there, I’m happy to look like a blowhard in the process. A lot of this is a bit of a “brain dump”, so it may seem a little scattered and disorganized. I should note that some of these things were actually not huge issues for me, but they could have been under different circumstances.

Being a good leader is hard

I’m going to be completely honest. I don’t think I was a very good captain. In fact, I think I was a pretty mediocre captain. If I had to go back in time and do it again, I would’ve done a lot of things differently. I kept the lights on, the team made progress on the initiatives we set out to work on, and we delivered a product in the end, but at the same time, we didn’t make as much progress as I would’ve liked and the product had flaws that we overlooked.

Here are the things that we did well during my tenure:

- In general, we built an open, friendly and professional leadership culture. The team was going through growing pains that year, and we instituted changes to make participation less intimidating to new members.

- We greatly improved our relationship with the university administration as well as with relevant external groups.

- We secured a record amount of funding and sponsorship, and ran a budget surplus which came in handy during the pandemic when funding dried up.

On the other hand:

- Under my watch, the organization became more bureaucratic and sclerotic, less nimble and in some cases unable to achieve things that groups with a fraction of the resources were able to.

- The final product we pushed out in the end was flawed from a systems/operational level, which led to a mediocre performance at the competition.

- I did not do a good job of keeping an eye on some sub-teams, and I did a very poor job resolving some major interpersonal conflicts that arose.

There are a couple of reasons why I think I didn’t do a great job. The main reason is simply immaturity: I didn’t have the life experiences or temperament to handle certain social situations gracefully. But there’s also reasons beyond the individual person that explain why it’s a tricky situation to be in.

Nobody really knows what they’re doing, yourself included

Being on a design team is a learning experience for everyone, the leads included. That’s, erm, by design. It’s a relatively low-stakes environment, but with relatively high technical sophistication, which means that the work is challenging, but failure has no real consequences (aside from the disappointment of your teammates, perhaps). For most people, it’s the first time ever that they’ll have been put in a situation like this, just like you.

The subteam and project leads are going to be learning how to manage people, set goals and expectations, work towards a long-term project, advance and improve their technical skills, and manage their time.

You can provide rough guidelines and philosophies on how to manage, but my opinion is that any granularity beyond that won’t take you very far at all. Management is so context-driven that you really just have to strike it out on your own. And at least at MRT, we hadn’t put much in place to ensure a smooth transition of leadership, partly because the team was so young (only having been ~3 years old at that point) and partly because documentation had been a bit of an afterthought up until that point.

There is very little authentic feedback on your own performance

There’s a common belief that most managers are bad. While I can’t directly comment on how true this is, I think it’s at least plausible, and not due to some universal indictment of managers. There are structural reasons at play—chief among them is that management occurs in a constantly changing context, with inherently low amounts of feedback.

If you want to rapidly improve and become good at something, it doesn’t suffice to simply do the thing a lot. Many people in North America spend a fair bit of time driving, yet the vast majority of drivers are mediocre. You also need rapid feedback on your performance in the thing you’re trying to improve at.

But herein lies the problem: it’s difficult to solicit genuine feedback on your management skills. People are not generally inclined to give negative feedback to someone who ostensibly has more power than them, and when they are, it’s often less precise and actionable than feedback that’s given to someone’s technical skills. Think of the classic trope of the artist trying to please their client, only to be told that the design doesn’t “pop”, whatever that means. People will often bring up specific instances where you did something they didn’t like, but without being able to link that to a higher pattern of behavior or decision making, it’s difficult to draw any conclusions. It can also be more difficult to swallow: the feedback also tends to be more personal, because management is fundamentally a social role and any faults and foibles you may have may reflect on your personality traits and quirks.

Given this, it’s no surprise that most managers will roughly stay at the same level of competence, and why the Peter Principle is so prevalent! Every jump in job responsibilities comes with increased expectations and scope of work, and places you in unfamiliar territory. It all comes down to whether you can pick things up fast enough to meet the new expectations, and in a management role, this self-improvement becomes much harder.

The work is surprisingly draining

Nobody becomes the captain of an engineering club with the impression that it’s a light workload. Even so, it’s still easy to underestimate how much work goes into everything. When I became captain, I told myself that I was going to set aside time for technical projects, but in the end only about 10% of my time was on technical work. My co-captain admitted that he basically didn’t get the chance to work on anything technical at all the entire year! You’d think that sending emails, doing paperwork and attending meetings would be relatively quick and simple tasks, but it adds up.

Paradoxically, managers think that they are working hard and that their position is stressful, but there’s a common perception from rank-and-file employees that managers are useless and don’t get very much work done at all. And I completely get it. If you viewed MRT from an outside lens, you wouldn’t think there was very much happening on the admin side: the captain just sends a couple of emails and slack messages, and attends meetings. It’s not like they’re working on any of the gnarly technical problems the leads have to deal with… I think the perceived output was far smaller than the input I gave the role.

Part of the reason is that since your work covers so many facets of the team, most people, on an individual basis, will see less than 20-30% of what you’re working on. But at the same time, this paradoxically makes you overestimate your relative contributions to the team compared to non-management roles, and how much work you actually have. I think this is part of the reason why Parkinson’s law is a thing. People involved in the bureaucracy see how much work they have, and they’re also the people tasked with resource allocation and hiring decisions, so naturally they will end up hiring more bureaucrats.

The present is all-consuming

The common adage is that good leaders need to set direction, be proactive, and provide vision. And that’s all true. But perhaps the more telling part is that these are not strict requirements to lead. That’s because leadership is an inherently reactive role. Your main job is to put out fires and deal with {CURRENT_EVENT} so that your subordinates, those tasked with actual technical execution, can focus on their duties. And boy, are there fires to put out!

Most of them are not a big deal. Just a small heap of smouldering cinders that could either die out on their own or be quickly stamped out. Others, however, can quickly devolve into 5-alarm infernoes that threaten to engulf the entire team. The problem is that the line between “important” and “urgent” is often hard to tell and you are ill-equipped to make the differentiation. Today, I don’t remember 90% of the things that kept me up at night back then, and they were probably ultimately inconsequential. I just remember that the urgency felt real. At the same time, I know that if the remaining 10% had gone unaddressed in time, we would have not launched a rocket that year.

Because of this, there is a sense of importance in everything you do. There is no such thing as a “typical month”, let alone a “typical year”. Each cycle brings with it new and unique challenges that each new generation of leadership has to tackle. All this running around leaves surprisingly little bandwidth for long-term thinking, and leaves you prone to falling into mimetic traps2.

As a warning: the constant urgency can make you feel like your actions have a disproportionate impact on the team, even when this isn’t the case. Things generally won’t fall apart overnight if you decided to take a day or even a week off. Make sure to keep a sense of perspective and that you’re not inflating your own importance, and set aside some time for yourself.

Most initiatives don’t work out

One of the recurring themes during my tenure was the question of space. Space to work. Space to store items. Space to perform tests. Due to external circumstances, we were in severely short supply, to the point where it wasn’t clear if we were going to have a place to even build our rocket. We ended up setting up a pretty good arrangement with the chemical engineering department, but the outcome was far from a sure thing at the beginning. Of course, that’s what people see, but they don’t see all the other possibilities that you explored and invested time into, that ultimately didn’t pan out.

A student engineering team is a big deal to the people within the team. In the grand scheme of things, it’s a nothingburger. You are still at the mercy of those who have the true power to decide whether your team thrives or dies: university administrators, funding providers, sponsors. And they’re at best, only tangentially invested in your success. At this level, there are very few “good” meetings with these people; at best, there are meetings that are “not bad”. Things only become “good” once you receive a signature and commitments in writing.

At the time, it was really frustrating to get these ambiguous and noncommital responses from people. Didn’t they care about the students?! Why aren’t they paying attention to my emails??? In hindsight, I realize that many of them, in particular administrators, were operating under the same constraints I was, just on a different level. They were taking a risk by trusting students—famously a demographic known for their good judgment and levelheadedness—to govern themselves, and they had very little to gain from doing so.

For every deal that works, there are often two or three that fell through, for various reasons. Most of them are outside of your control. And because of how open-ended everything seems to be, you’re constantly asking yourself if there’s something else you could be doing that could move the needle and turn a no into a yes.

You have only indirect control over the success of projects

A lot of people who end up in these kinds of roles have type A personalities and put a lot of pride into their work and into the success of projects that they’re tied to. But once the scope of work becomes large enough, it’s no longer possible to attribute success to any one person’s specific set of actions. You’re now two steps removed from the process of physically building the product.

This means that your actions no longer contribute to the product quality.

You can no longer have a handle on everything

Up until this point, the vast majority of group projects I had worked on had been in an academic or very small team setting, where the amount of people contributing to the project was never larger than ~8 people at most. At that scale, it’s indeed very possible to be familiar with every detail of the project.

The problem is similar to Brook’s law: the space complexity of large, collaborative programs grows superlinearly. Your ability to stay up to date with $n$ tasks and projects is $O(n)$, i.e. putting in 10% more time means you can stay up to date with 10% more projects. But for the people working under you, they also have $n$ projects and direct reports, so the amount of things to keep track of grows by $O(n^2)$. Some talented people are able to keep track of more things at once, but the scaling law will eventually win out: at some point the amount of stuff going on will exceed your ability to keep abreast of it.

When laid out, it all sounds completely self-evident, but what it subtly shifts the way you frame issues. The questions you should be asking yourself become “How should I be spending my time?” and “Does X need my intervention?” rather than “What am I going to work on next?” Your thinking becomes process-oriented as opposed to results-oriented.

Your information quality gets worse

In fiction, one of the most fundamental literary devices is the use of an unreliable narrator. It’s one of the first things that’s noted about a book, and it makes analysis much more challenging, because now the reader also has to determine truth based on the narrator’s supposed personality quirks, biases, mental state, etc.

In real life, everyone is an unreliable narrator, to varying degrees. Everyone has biases, and more specifically lens through which they analyze a problem or situation. And the more layers you have to go through, the worse it gets (at MRT though, it was at most 2 layers, so this wasn’t a huge issue). People often bring up the telephone game to illustrate how information gets distorted simply by passing through people. Now imagine when the people relaying the message are not necessarily incentivized to relay accurate information.

People on the front lines have the best idea of what the underlying reality actually looks like, but they are also likely to overestimate the relative importance of the issues that they are facing. Conversely, people who are a step removed from the actual day-to-day operations can be good at pointing out long-term structural issues, but they will have little insight on how to fix them as they won’t know which courses of action are realistic.

There’s another aspect to it, which is the power dynamic. People will not naturally interact with a manager the same way they interact with a peer. At MRT, it wasn’t particularly bad since I didn’t make hiring decisions (anyone who wanted to join the team was welcome to join) and I couldn’t unilaterally “fire” people. But it gets worse the larger an organization becomes.

Once you realize this, it becomes clear that one of your main duties is to figure out and tap into good sources of information, and then aggregate them. That’s going to be an inherently very personal judgement, based on your assessment of other people and their trustworthiness. Your ability to accurately understand what’s going on now becomes tied to your ability to judge people.

Cause and effect are difficult to discern

Rocketry is an extremely unforgiving hobby—in the words of Tom Mueller, SpaceX’s ex-CTO of propulsion: “There are a thousand things that could happen when you light a rocket engine, and only one of them is good.” Student teams will spend the better part of a year designing, building, and testing their rockets, with the cumulative time commitment in the thousands of hours, all while juggling their schoolwork, jobs and whatever other commitments they may have. Finally, they make their way down to the competition, install their rocket on the launch rail, press the small red button, and watch with anticipation, hoping that something doesn’t go horribly wrong.

There are three phases to the flight. The powered ascent phase, where the rocket engine is active and accelerating the vehicle upwards, is the most intense and typically lasts less than ten seconds. The coast phase continues until apogee is reached thirty seconds later, shortly after which a drogue chute is deployed to slow the descent. The controlled descent phase continues for 4-5 minutes, after which the main parachute deploys and the rocket lands a bit under a minute later. In total, the flight lasts about 6 minutes, but the majority of the potential failure points occur in the first minute.

Furthermore, since launching a rocket is both very expensive and very logistically complicated, most teams will only get to launch their rockets once or twice a year. The competition is often the first—and sometimes last—time a rocket is flown. That leaves very little room for failure. Even something as small as using the wrong screw thread tolerances in your parachute deployment assembly can doom a flight.

Engineers are familiar with root cause analysis and its use to identify and mitigate sources of failure. A common rule of thumb is the Five whys: any root cause is discovered by asking “why?” five times. Usually, the first couple of whys are purely technical in nature, but as they become higher and higher level, the human factor becomes involved. This is where things get more nebulous and messier. Was the seal not properly checked due to lax maintenance standards? Or were the maintenance standards fine, and instead there was a “culture of laxness”? How do you even define that? And what about the counterfactual: would a “culture of non-laxness” have prevented the incident? What could you even have done to prevent a culture of laxness? The solutions may seem obvious on paper, but things involving humans rarely have a way of working out the way you expect them to on paper…

Non-alignment is the default state

This one is a bit more specific to MRT, but I think there are also parallels to be drawn from elsewhere. Student engineering design teams demand a ton of unpaid time and commitment, often 10-20+ hours a week, from people that are already hard-pressed for time and energy. A lot of people join engineering design teams to pad their resumes, and MRT was no exception.

It turns out that there are much less intense (or better paid) activities that will be just as beneficial to helping you get a job. Design team participation is helpful for landing your first internship, but after that, prospective employers are overwhelmingly going to consider your professional experience over any extracurriculars. At that point, any further time investment into a design team will have diminishing returns, viewed from a pure employability perspective. Indeed, that’s what some people did: they joined the team, stuck around to make some minor contribution they can slap onto their CV, got a job, and then we never heard from them again.

At the same time, this wasn’t the case for many people. They stayed on even after they had “made it” because “rockets are cool” was a sufficient motivator. That’s a really awesome thing to see, but depending on passion to get the job done is also a fickle game. It means things that are more “interesting” will get disproportionate amounts of attention even if they’re less essential to the group’s core goals.

In this narrow sense, most of them won’t be as invested as you. You are the central locus, in a position that selects for investment in the team: not any particular project, but the team as a whole. Just like how business owners and event organizers often express discontentment with the initiative or drive of their employees, because they expect their employees/volunteers to work with the same gusto and passion that they do—they’re projecting their own passions and interests onto other people who don’t have the same motivations or investment into the enterprise.

Sometimes, it would frustrate me that people would be unwilling to put in the legwork to do something, or to see a project stagnate. But this is completely normal! If anything, this should be the expectation! Of course, expecting it doesn’t make it any easier. Sometimes it will feel like herding cats to get an initiative off the ground.

Decision-making becomes harder

So far, I’ve mostly discussed the social elements of being the head honcho. And they’re all relevant, but they paint an incomplete picture without talking about the main function of the captain role: being the chief executive. You are there to make decisions, and to solve problems.

This, in turn, makes the experience qualitatively different from just being a technical lead or project manager, because you have the de facto last say. If you are a stubborn person who likes doing things your way, then this can be a good place to be. But it also means that the decisions you have to make are generally going to be trickier, more open-ended, and more ambiguous than lower down the chain. This is simply because if a problem has a clear-cut, unambiguous solution, then it will never reach you because someone lower down the chain would have already solved it.

Furthermore, if a problem reaches you, then you have to address it, because if you don’t, no one else will. Saying “this isn’t my problem” is not an option. Not only will your decisions become tougher, you’ll have to make more of them. The decisions are not harder in the sense of being able to “grasp the issues”, but in more subtle ways that I will outline in the next few sections.

You can no longer please everyone

Nicholas Taleb often expounds on the importance of having “skin in the game”, and while I was able to appreciate his argument in an academic, sterile sense, it was only after my tenure as a captain that I really got what he meant.

It’s easy to be considerate and virtuous in the eyes of your peers when the choice is simply between being an asshole and not being an asshole. And most of the time, people will choose not to be assholes, barring momentary lapses in judgment or whatever character flaws that everyone possesses to different degrees. But what will you do when there will always be someone unhappy with your decision? What do you value more, and what do you value less?

Most people have never made and will never have to make these kinds of calls. Everyone can see the results of these decisions, even if they don’t see what went into it. And everyone can assess for themselves whether you made the right decision or not. This assymmetry means that you will be judged in ways that will feel unfair, while at the same time very few people will be able to empathize with your situation.

Below a certain level of scope, compromise is possible. Above this, you are often dealing with resource allocation problems, and you are the final person responsible for the outcomes. At a middle management level, sometimes you have to screw over your team, but that’s often because some higher-up has forced your hand, and you regretfully have little say in the matter. But at the top, there’s no hiding behind someone else or deflecting responsibility. When you get down to it, sometimes you will necessarily be screwing someone over no matter which side you pick.

You can alleviate this by having a committee make executive decisions, but this is far from a silver bullet. The tradeoff is that your organization becomes slower moving and less responsive, since you now have to build consensus to spur action, and the overall vision gets diluted. After all, the term ‘design by committee’ is a pejorative: a sign of a mediocre product focused on pleasing everyone rather than making difficult tradeoffs.

The environment is fraught with uncertainty

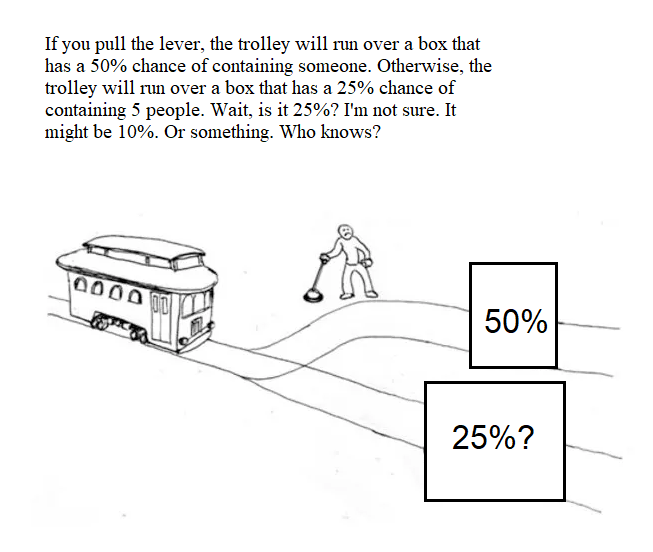

When most people think of moral or ethical tradeoffs, the trolley problem is usually one of the first things that comes to mind. It’s a situation where the person has to choose to make a difficult moral tradeoff between intervening and killing one person vs. standing by and letting 5 people die instead. Anyone who’s spent slightly more time online will be familiar with various trolley memes, where the scenarios become increasingly absurd and humorous.

I enjoy trolley problem memes, and as for the thought experiment itself, I appreciate how it illustrates that the lack of an action (i.e. not pulling the lever) is in of itself a decision. When the buck stops with you, you will end up making a lot of trolley problem decisions, in the sense that sitting on it and hoping the problem goes away is in of itself a decision. But if I had to make a trolley problem meme that was more representative of what real decisions look like, it would be something like this:

Obviously, it’s even more ambiguous than that because these percentages aren’t handed to you on a silver platter! You could attempt to collect quantitative information instead to make an “objective” decision, but life usually doesn’t readily provide you with easy-to-measure data. That takes time, and effort. Trying to quantify the choices is in of itself a decision. It’s not a foolproof one either; it can easily lead to bickering over methodologies and quantities and ultimately analysis paralysis.

This is why there are so many different decision-making systems for managers: decision matrices, the Cynefin framework, Rumsfeld matrices, and much, much more. They help people contextualize their information and the choices they have to make, and they bring some semblance of order into the messy, messy chaos of reality.

The other side of this is that it’s easy to deflect criticism: some people have a different mental model/probability assessment—maybe they’re standing next to one of the boxes on the track and they know for sure that it’s safe to deflect the trolley in this direction—and indeed for this specific decision they would be in a better position to make the correct choice, but that doesn’t mean that they would a priori have a better mental model for all decisions. Furthermore, their message is probably being relayed to you imperfectly. It’s pretty rare that you’ll actually have a situation where someone is screaming: “HEY, I AM NEXT TO THIS BOX AND I AM PRETTY SURE THERE IS NO ONE IN HERE”. And sometimes you’ll also have someone standing near the other box, yelling “I’M PRETTY SURE THERE IS NO ONE IN HERE EITHER”. Who do you trust, and why?

Smart people are not necessarily better at making “correct” decisions, but they are better at coming up with post-hoc rationalizations of why their decision was correct, even in the face of evidence suggesting otherwise. It takes some genuine introspection and humility to admit to yourself that your reasoning was flawed, and to adjust your mental model and beliefs accordingly.

The decision space is huge

A lot of what I’ve described, while challenging, could still be applied to technical problems as well. After all, many purely technical decisions have uncertain outcomes. It’s not like the tradeoffs between using a single-separation, dual deployment or double separation system are immediately obvious either. I would argue, however, that technical decisions are still qualitatively much easier.

In a nutshell, technical problems tend to be much self-contained. Oftentimes, any particular technical problem will boil down to two or three practical choices once it’s sufficiently studied. In contrast, for something like implementing a new team policy, there’s an almost infinite number of possible solutions. Each decision carries with it a bajillion micro-decisions: implementation details that can make or break a solution.

It’s much more likely for you to overlook an idea than if you were tasked with designing (for example) an engine ignition system, since that possibility space is constrained by physical laws. Not uncommonly, you’ll spend a lot of time thinking about a problem, brainstorm ideas, painstakingly debate which route to take… and then someone will just suggest a far better idea the instant you announce your solution. It’s like attempting to find something via Google, failing to do so, and then having someone else punch it the exact right combination of keywords and finding it within 5 minutes.

When this happens, you’ll probably either end up looking dumb, or stubborn and recalcitrant, regardless of however you choose to respond. Nobody wants to look dumb, but being unresponsive and unwilling to listen to feedback is worse. You might just have to swallow your pride and backtrack.

What does this mean?

If you’ve gotten this far, you might think that this all seems like vague whining about how upper management is hard. That’s not completely off, if reductionist. The common theme among all of these points is that the higher you go, the less your decisionmaking is based on ground truths, i.e., “facts”. There’s just simply too much information, too many moving parts, too many uncertainties, too many feedback loops for any single person to make sense of it all. Abstractions become a necessity—it’s your worldview and mental model of a situation that let you assign probabilities and weights to each of the corresponding choices. More often than not, decisions need to be made based on a “gut feeling”. Your choices become more-or-less a reflection of your specific personality traits and your mental model of the world—ironically, making the person with the most influence in the organization the worst person to make completely rational decisions.

But rationality is not a prerequisite to success or correctness, and in many cases there’s not enough information to make a well-informed decision anyway. It seems to me that people who do succeed in corporate leadership and entrepreneurship have tapped into an accurate mental map of the underlying reality for any number of reasons. Those reasons almost never originate from a “rational” set of inferences. Their reasoning is often fluid, intuitive, and almost instinctual. Steve Jobs didn’t get his opinions on, for example, industrial design, from doing a thorough literature review of the psychology of aesthetics.

Elon Musk’s “first principles” approach has often been touted by the corporate media, but anyone who’s actually tried to put it into practice will realize how trivially unhelpful it is. It may be based on physical first principles, but starting a computer chip business on the premise that we’re not close to Bremmerman’s limit is probably not a recipe for success. Where do you stop? Any application of first principles reasoning that isn’t totally trite requires some pretty significant assumptions to be made. What is a “useful” first principle to keep in mind, and what isn’t? Musk works well within that framework because he has an intuitive ability to determine where that line should be drawn (most of the time). This doesn’t say anything about the usefulness of a “first principles” approach for other people!

It’s easy to dissect with the benefit of hindsight why the iPhone succeeded but the Segway did not. To make that assessment ahead of time, though, at the right time, no amount of “market research” will get you there. By the time it does, you’ll have been scooped by someone who was able to make the same inferences in the absence of complete information.

Recently, there was some discussion about texts from prominent tech entrepreneurs and investors that were released as a part of the Twitter/Elon Musk case. A lot of people have expressed shock at how “dumb” these Silicon Valley elites sound and how they just seem to be throwing ideas at the wall without any real analysis or solid reasoning behind them. But I don’t think this is particularly surprising. Their real-world success came about because their instincts were on the money for a bunch of major bets with real stakes. At least in their eyes, they have reason to believe that their instincts are generally correct, even if the result will only become evident much later down the road.

That explains why they tend to double down when challenged on their assertions, why egotistical behavior goes unpunished, and most notably why their failures occur the way that they do. They mistake the map for the territory because they mistakenly think their mental model accurately covers more realities than it actually does. One example is Jim Clark, who after a successful innovative stint in Silicon Valley with SGI and NetScape, moved into healthcare to try to apply the same ideas. Unfortunately, most of the ideas flopped due to their naive understanding of the industry. It’s important to keep this in mind even as your successes pile up: it may mean that your mental model is particularly well calibrated for certain realities, but it doesn’t say anything about how well the model can be extrapolated.

Advice

The challenge with giving leadership advice is that everything is so context-dependent that usually specific advice (or “overfitted”, in statistical terms) is not helpful. At the same time, trying to generalize advice results in vague, wishy-washy soundbites that wouldn’t seem out of place on a motivational poster.

With that said, here are some points I think are particularly salient.

- Understand yourself and your own strengths and weaknesses. If leadership inherently requires a personal touch, then you need to have a high level of self-awareness to have any hope of being able to draw lessons out and improve your skills. Try to be introspective and understand why you feel compelled to act a certain way, even if you don’t like the answer.

- Write down the reasons why you are making a decision a certain way. These reasons don’t have to be made public. But this will force you to explicitly list out all the considerations floating around in your head, and give you better insight into your own mental model and decision-making framework. Writing something out also generally requires you to fully understand the issue at hand. You will be in a better position to justify your reasoning later, if you ever need to revisit the decision.

- Don’t take bad decisions personally, but as an opportunity to adjust your mental model. Nobody starts out with having a perfect understanding of human social dynamics or project management or systems engineering. It would be absurd to expect anyone to have a perfectly representative mental model of reality. If someone criticizes your decisions, do not take it as an attack on you, but rather as a critique of your mental model and any potential blind spots you may have.

- Praise in public, criticize in private. This is nothing particularly groundbreaking, and is in fact an extremely common rule, yet I repeatedly failed to do it. It is one of my biggest regrets about how I went about things at MRT. Nobody enjoys being publicly humiliated. It’s an easy way to damage morale and build resentment.

- Be an example of the culture and beliefs you want to see. If there’s anything that could uniquely be attributable to the success or failure or a project, it’s culture. And culture flows from the top down. People will notice when you take things seriously vs. when you don’t. The people you interact with will feel incentivized to do things that they think you’ll react well to, and disincentivized from doing things that they think you’ll give them a hard time for. That’s why micromanagement, for example, creates a vicious cycle, as it kills initiative and prevents people from organically learning from their mistakes. This in turn reinforces the notion that you have to tell people “how to do their jobs right”.

- Respect, but don’t sweat the small stuff. Remember to keep some perspective. What’s the worst thing that could happen if you decline an event invitation, or fail to apply for some funding? At the end of the day, we’re all here to have a good time. Optimizing for fun is not the worst idea out there.

Building a community is awesome

There’s one more thing that I want to talk about.

There is the concept of the McGill Rocket Team as the legal entity. It exists in the databases and spreadsheets of McGill’s administration and the engineering student society, in the form of financial accounts and contact information. Then, there is the concept of MRT as an institution, which is nothing but a set of ideas instilled in its members, who then go on to perpetuate the institution through their actions and beliefs. It only exists because a core group of ~60 or so people believe in its existence.

MRT was a very young team when I joined, with only two years of experience under its belt. The team was still figuring out a lot of things, like how to structure its design process, how to recruit people, how to organize the team, and how to produce a high-quality product while providing an educational experience for its members. I got to witness these processes and ideas get built up around me, collectively morphing into what we call the McGill Rocket Team.

I don’t keep too up-to-date with their activities these days. And on the occasion where I do hear from them, MRT is still very much alive today. It’s become one of the more bigger, more well-funded, more established and more ambitious design teams at McGill, and it’s clear that the team is providing an awesome and enriching experience for its members.

People who were on the team during my tenure have graduated or moved on. There’s few people left who would remember me at all. Most of the practices and initiatives I implemented have been scrapped or reworked. At some point, my contributions will become entirely forgotten. The lessons learned from the past will still be incorporated into the team’s actions, but will no longer be traceable to any single individual. What remains in place is bigger and more significant than what anyone could hope to achieve on their own.

And beyond the cool projects, the career benefits, the networking events, the personal development and the unique memories, that’s why it was all worth it.

They’re doing quite well these days, but pretty much none of that comes from my efforts. ↩︎

The biggest example of this are sponsorship requests. Student engineering teams are perpetually strapped for cash, and funding is a constant struggle. You’re always looking for opportunities to get free parts and materials, or even a buck or two. At one point I was trying to find sponsors for candle wax. Then I realized that I had only a few months left on my tenure and that we were already running a budget surplus. So I eased off. A little. ↩︎