Making Industrial Electrosynthesis Viable

The hot word in the power grid these days is ‘dispatchability’. The ability to adjust power output, or on the other end, adjust power consumption on demand is vital to balancing the grid1. Dispatchable generation and dispatchable loads will become increasingly valuable with heavier penetration of non-dispatchable renewable generation, such as wind and solar.

The favorable economics of renewables and zero marginal cost of production mean that in many cases, it will make economic sense to overbuild generation capacity and simply curtail production when it isn’t needed. An even more economically sensible option is for large consumers with load flexibility to perform demand response, turning up their consumption when electricity is plentiful and turning down or even idling when generation is low.

The electrification of chemical synthesis is a great opportunity to simultaneously decarbonize heavy industry while building more demand response capability. While there are obvious and straightforward examples like replacing combustion boilers with electrical heaters or heat pumps, one of the biggest opportunities lies in electrifying the chemical reactions themselves. Many speculatively optimistic articles have been written on the potential of industrial electrochemistry. What are we to make of this?

What do we make with electrolysis?

We’ve been performing electrolysis at industrial scales for over a century. Notable examples include:

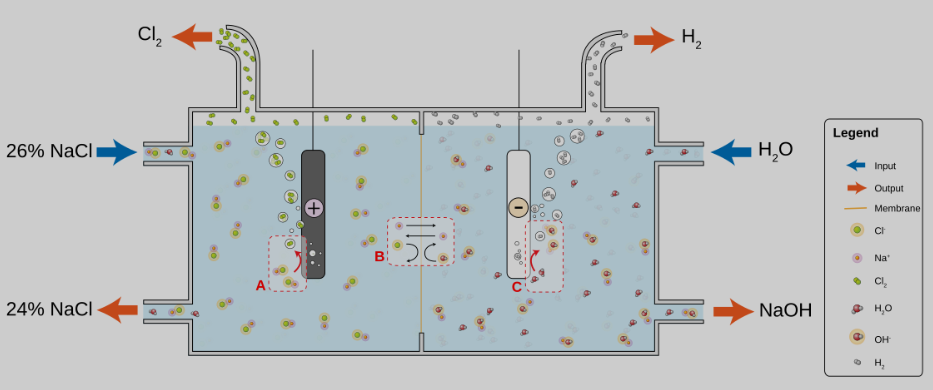

- Chlorine gas, and sodium hydroxide from the chloralkali process.

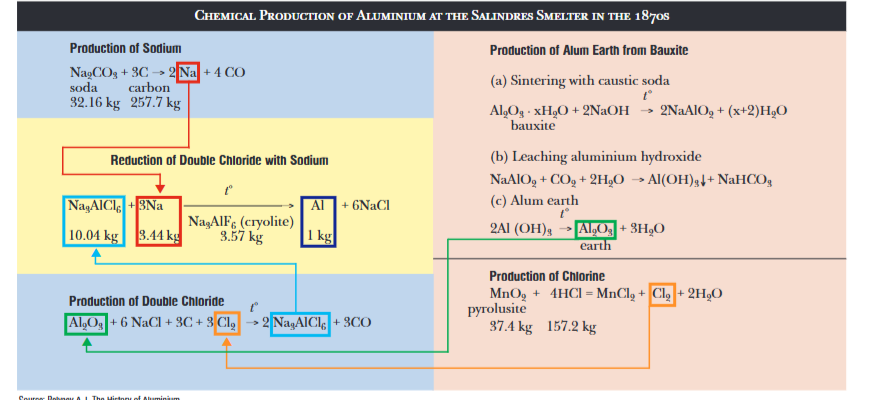

- Metal refining. The Hall-Héroult process for aluminum is the most well-known, but lithium, magnesium, potassium, sodium and calcium are also refined via electrolysis.

- Production of chlorates and perchlorates.

- Fluorination of carbon compounds.

These are important applications and most of them, particularly aluminum refining and chlorine production, are essential to the industrial supply chain. But compared to chemicals made via thermochemical synthesis, the list is quite small. In general, thermochemistry has a significant cost advantage for reasons I won’t get into in this essay (although I’ll probably write something at a later date).

There’s one missing notable example: hydrogen splitting via water electrolysis, a.k.a. ‘green’ hydrogen. Given its prominence in the decarbonization narrative, it deserves a section of its own.

Electrosynthesis should focus on industrial applications

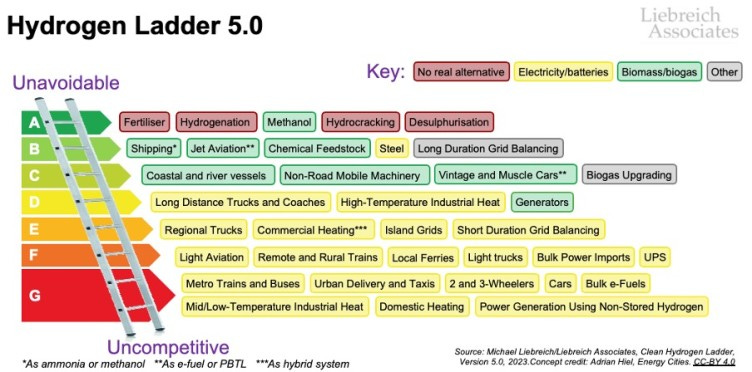

Hydrogen is an extremely useful molecule for industrial chemistry. It’s easy to make and is an excellent reducing agent. By my count, 8 out of 10 top use cases for hydrogen on Michael Liebreich’s celebrated “hydrogen ladder” involve chemical synthesis.

Hydrogen as a standalone energy carrier, such as for home heating or in vehicle fuel cells, is… less useful. There are many well-documented reasons for this across the entire value chain. A full exposition is beyond the scope of this post.

Chief among them, though, is that hydrogen distribution is an enormous, expensive pain. It’s much more cost-effective to keep most hydrogen production heavily centralized and co-located with the plants that need it. This is the main use case that should be planned around, rather than a consumer-level “hydrogen economy” that is unlikely to ever materialize.

The same applies to other potential chemicals. They’re mostly sold to industrial customers who use them to make finished products. (In fact, aside from water, gasoline and possibly natural gas, I can’t even think of any commodity chemicals that have a significant consumer market.)

Green hydrogen has been a boondoggle

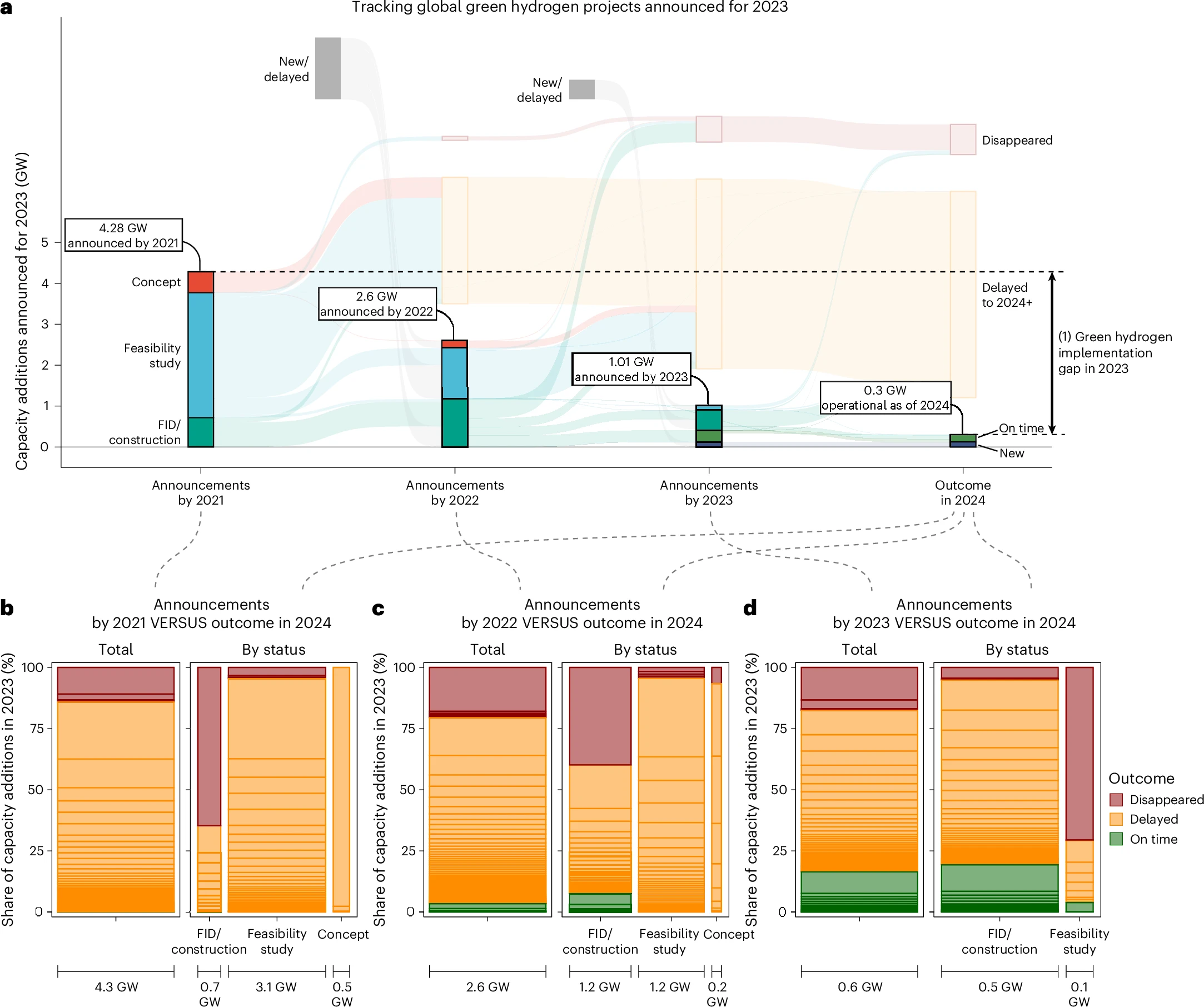

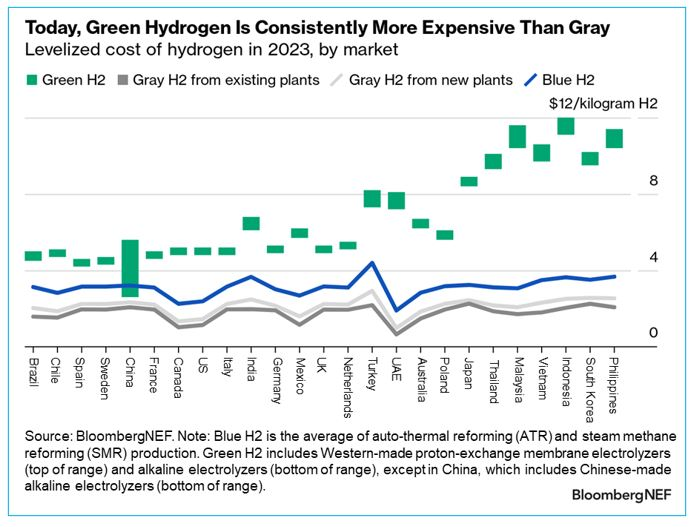

A particularly influential 2020 report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) predicted that costs could rapidly drop from economies of scale and that deployment of hydrogen electrolyzers could become widespread by 2030, allowing green hydrogen to reach parity with ‘gray’ hydrogen.

Those predictions haven’t borne out. The reality has been far more sobering—the majority of built projects have run into severe cost and schedule overruns and green hydrogen production costs aren’t anywhere near fossil-based alternatives.

The track record is dismal: globally, not a single green hydrogen project planned for 2021 is on schedule. Many planned projects are now in limbo, and will likely never reach Final Investment Decision (FID).

This brutal state of affairs belies a simple truth: electrifying the chemical industry is going to be very difficult. The technology is still in its relative infancy, and the economic case without subsidies isn’t there.

While green hydrogen is the poster child for industrial electrification, I think it’s in many ways a square peg being jammed into a round hole, and its problems can lead to lessons for the rest of the industry.

Green hydrogen is fundamentally a poor fit in commodity chemical production

Green hydrogen plants have commonly been conceptualized in the context of a massive expansion of the hydrogen economy, where hydrogen is ubiquitously distributed, consumed and traded. In this speculative light sci-fi telling, these plants are depicted as huge standalone facilities located in light industrial parks surrounded by shrubbery and trees, with their subsystems arranged in nice orderly arrays progressing in linear fashion from inputs to outputs.

These plants gulp up water and electricity, and only emit high purity hydrogen in a form intended for offtake, i.e. compressed to very high pressures (250+ bar) or liquified, ensuring they can slot into any process that uses hydrogen.

It’s an appealing vision for reaching massive scales: a simple high-level “universal interface” that—at least in theory—can slot into many different industrial applications. Just copy-and-paste the same plant over and over. Unfortunately, this sort of arrangement is in practice a terrible way to economically produce chemicals.

Hydrogen isn’t a good endpoint in the chemical supply chain

Hydrogen isn’t the most convenient or desirable molecule to keep around. The engineering and safety requirements are complex. Carbon steels—the most common materials of construction in chemical plants—can’t be used for high-pressure applications due to embrittlement. Leaks are hard to prevent. Storage is incredibly expensive.

Out of approximately 100 million tons of hydrogen produced annually, the vast majority—around 85-95%—is immediately consumed onsite in downstream applications such as methanol production.

What this means is that actual process interfaces for hydrogen have a great deal of variety. The pressures, temperatures, flow rates, and purities needed for hydroformylation are very different from those needed for hydrocracking.

Poor process integration results in inefficiencies

Ask any seasoned engineer who’s delivered big projects, and they’ll tell you that the easiest, most reliable and most effective way to reduce costs is to eliminate requirements you don’t need2. Figure out what the system actually needs to do, and then optimize for only those things. No more and no less.

By the same token, the easiest way to blow up the cost, complexity and schedule of an engineered system is to stipulate that it be “flexible”. A simple, modular and “universal” interface with the outside world can be elegant and versatile but can come with significant downsides.

Not knowing anything about the downstream application means a designer has to assume the most conservative scenario. They might need to plan for having high-pressure compression systems, which can be a significant cost contributor. Hydrogen is a particularly challenging gas to compress with turbomachinery due to its low molecular weight. Axial and centrifugal compressors, which are more cost-effective for high-capacity applications compared to diaphragm or reciprocal compressors, are still not widely available for pure hydrogen.

Other potential synergies are limited. PEM and alkaline electrolyzers operate at temperatures ranging between 25-80C. The heat they produce is very low-grade, and not very useful for anything. Dedicated cooling systems are required.

Meanwhile, process turndown capability will be limited by the weakest link. It doesn’t really matter if your hydrogen electrolyzers can turn down to 10% if the downstream reactor can only turn down to 50%. Heavily interdependent systems, generally speaking, are challenging to ramp up and down—oil refineries typically have a minimum of 60-70%.

Customers don’t need what they’re being provided

Unfortunately, there isn’t a straightforward way to “simplify” water electrolysis further or loosen its requirements, at least as a standalone process. They’re inherent to the process.

One feature of water electrolysis is that the produced hydrogen is very pure. The only other species in the product stream are water and oxygen (due to leakage in the stack). The subsequent drying and treatment steps are relatively straightforward. It’s not uncommon for electrolyzer manufacturers to advertise hydrogen purities of >99.999%.

Who actually needs this level of purity? Combustion engines and furnaces don’t really care what they’re fed as long as it burns in air. If the hydrogen is used to make chemicals, it’s just going to end up being mixed with other (probably fairly impure) ingredients such as carbon dioxide or nitrogen. It’s like preparing pasta water by buying deionized water and then adding salt to it.

In fact, the oft-quoted benchmark prices of \$1-2 per kg for “gray” hydrogen can be misleading in an industrial context. Even though they’re accurate, they’re referring to “merchant” hydrogen. This assumes that the buyer needs pure and compressed hydrogen and the cost of these steps is taken into account. When the hydrogen is “captive”, in other words, produced in a steam reformer, never isolated and immediately used, the “effective cost” can be difficult to determine but it can be significantly less than \$1/kg.

The other product hydrogen electrolyzers make is high purity oxygen (after removing water). They make a lot of it! By mass they make 8 tons of oxygen for every ton of hydrogen. But it’s usually just vented. Many vendors don’t even bother listing it as a product. While oxygen isn’t the most valuable industrial chemical, getting a high-purity stream with multi-ton-per-hour flow rates isn’t trivial.

In both cases, value is being thrown away because it isn’t wanted. That’s fine in some cases because the underlying product or service is inexpensive enough and there are other considerations at play. But “this product is really cheap so we don’t have to get our money’s worth” is quite obviously not the case for green hydrogen.

Production flexibility isn’t a silver bullet

Electricity is the largest cost component of producing green hydrogen. According to EIA data, \$50 per MWh would be among the lowest rates for industrial customers in North America. That wouldn’t be anywhere near low enough for cost parity: at an energy efficiency of 80%, the electricity alone would cost about \$2.50/kg H2. You’d be underwater even if the plant itself was completely free.

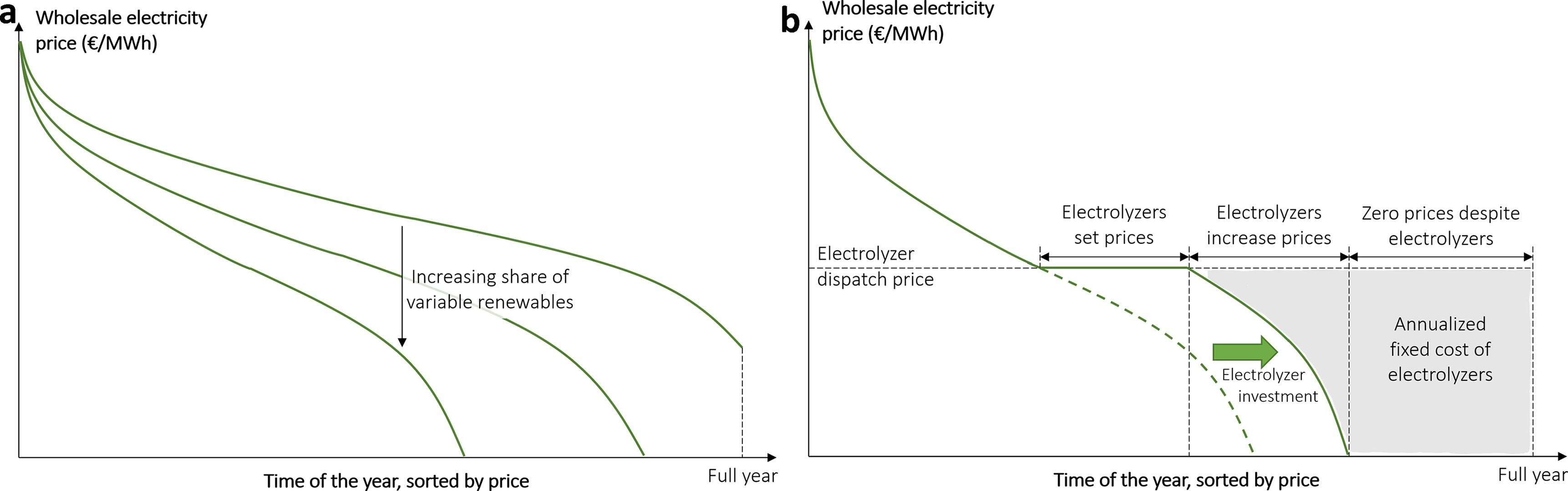

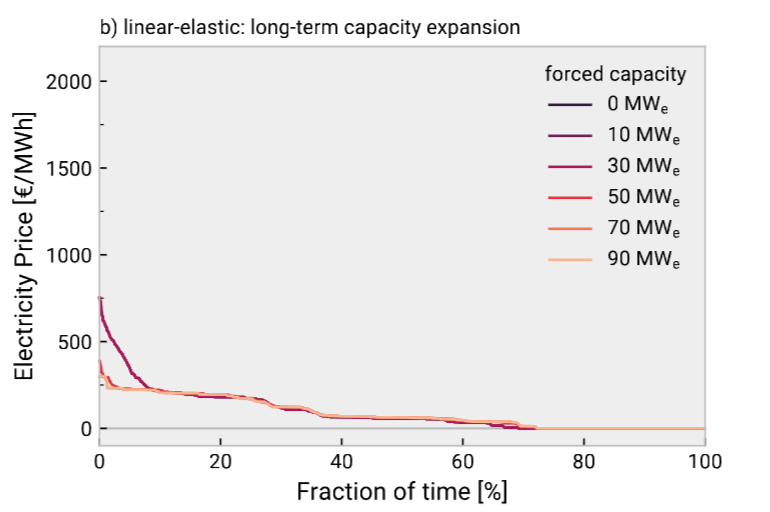

There is one possible solution. When renewable capacity gets overbuilt on grids with limited storage capacity, the price duration curve becomes heavily skewed, meaning that we have very low prices most of the time and very high prices for a small amount of the time. In theory, electrolyzers can exploit this by operating flexibly. The idea is pretty simple: you forgo signing a power purchase agreement (PPA) and instead opt for locational marginal pricing (LMP). You run your plant when electricity is cheap, possibly below a threshold value, and shut down when it’s expensive.

This will undoubtedly be beneficial, but how much will it help? The answer is complicated.

Any decrease in utilization is an economic trade-off. Residential demand-response schemes are win-win because opting to take a shower or do your laundry later has no real adverse consequences3. Industrial demand-response, in contrast, always presents an opportunity cost: turning down your electrolyzers doesn’t mean postponing production, it means reducing total production. Any potential savings from cheaper electricity prices must be weighed against the fact that capital expenditures must now be amortized over less units of production.

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that the duration curve is literally a Pareto distribution such that 80% of the cost comes from 20% of hours. If so, reducing uptime to 80% could get you an average electricity price of ~\$12/MWh. That’s a great deal! You can probably get a levelized production cost under \$2.00/kg H2 and even close to \$1.00/kg. But how long will it last? Such a huge imbalance in prices presents an arbitrage opportunity, not just for industrial electrochemistry, but for anyone who can consume lots of electricity. And you can make many business cases close at \$12/MWh.

Over time, as more flexible loads and more storage is installed to exploit this arbitrage opportunity, the price distribution will level out thanks to the elasticity of demand.

There is no reason to believe electrolysis, among all possible demand-response tools, will be the marginal price setter. Even if you think this is currently the case, will it continue to be the case in 5 years? 10? 20? Do you know? Does anyone know? Is this an acceptable risk for a project possibly requiring hundreds of millions in capital investment with a payback period of 5-10 years?

While load following can be a complimentary strategy, I’m skeptical that it alone can form a basis for a greenfield electrolysis project. There’s simply too much uncertainty, over too long of a time horizon for the potential returns.

Will massive modularity and scale get us over the hurdle?

To summarize so far, green hydrogen is a bad fit for existing industrial applications and will struggle to provide a compelling and cost-effective product. These challenges are structural and will be incredibly difficult to solve.

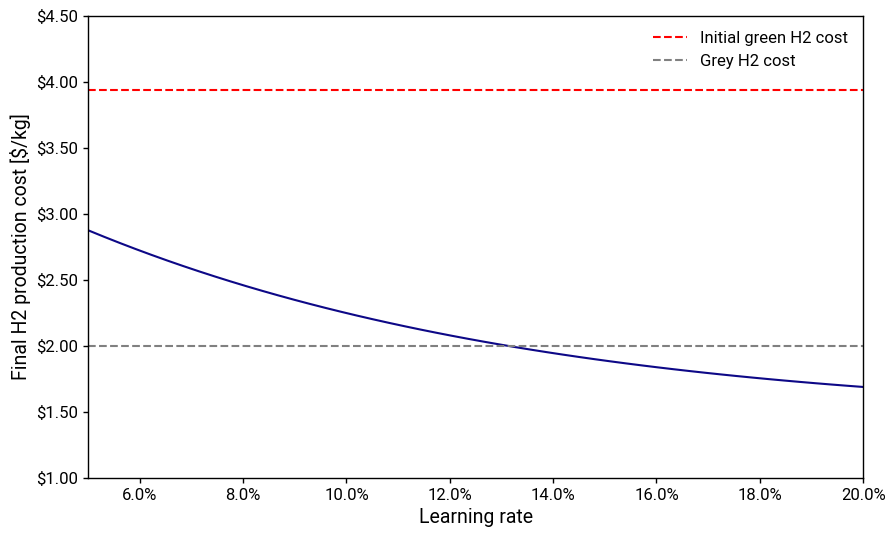

What can we do about it? The increasingly prevalent answer, it seems, is to double down and try to “brute force” the issue: invest into more R&D to eke out every last bit of performance, try to modularize everything, build huge electrolyzer factories, and hope that “learning curve magic” brings costs down to a competitive level. While I have some misgivings about this from a technical perspective, they don’t need to be litigated here4. Instead, let’s work through some back-of-the-envelope financial numbers.

Where it’s been tried at scale, green hydrogen has achieved production costs around \$5-8/kg. To compete with steam reforming, that needs to drop to at least \$2/kg, and more realistically less than \$1/kg. That’s a 60% cost reduction using the most generous numbers from these ranges.

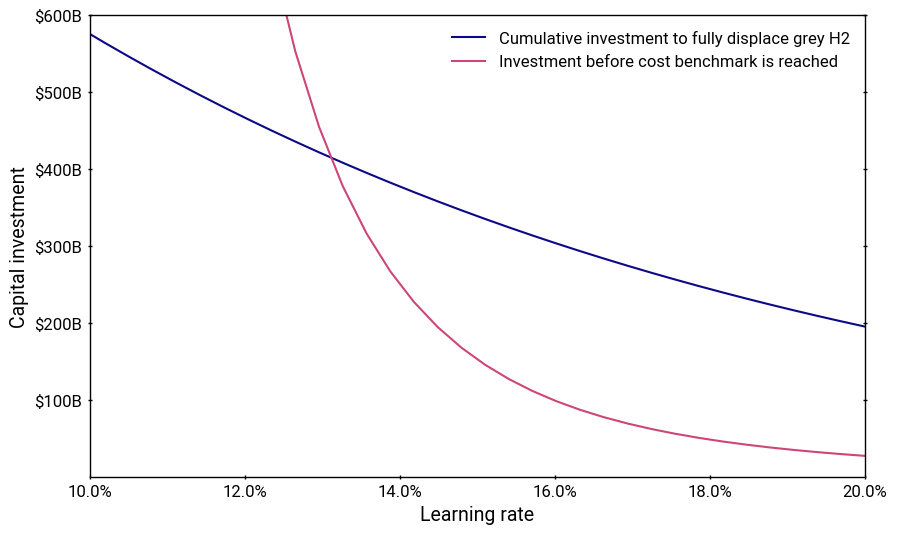

According to the IEA, there was about 300 MW of installed PEM electrolyzer capacity by the end of 2023. To completely electrify all current use cases of hydrogen—approximately 100 million tons per year—we’d need, depending on your assumptions, somewhere between 600-1000 GW of installed capacity worldwide.

If all of that is achieved with only PEM electrolyzers, that represents about 11 doublings of cumulative production. Then, if we very generously assume a 20% learning rate for the entire hydrogen plant, including balance of system, that gives us a plant capital cost of 8.5% relative to today’s \$2500/kW—roughly \$210/kW. If we again generously assume that these plants will have an average electricity price of \$30/MWh at a capacity factor of 90%, then gets us to a production cost of about \$1.70/kg with a rather pedestrian 10-12% cost of capital.

To get to this point would require a cumulative capital investment of 200-300 billion dollars for the plants and likely tens of billions more for the factories. This may not seem that high, but keep in mind this doesn’t account for the losses from the unprofitable plants over their depreciable lifetimes, which will cumulatively total in the hundreds of billions or even trillions. And the generous assumptions are piling up. What if the learning curve turned out to be 15% rather than 20%? That would nearly double the required capital investment, yet it too, is likely to be too optimistic.

Who’s going to be willing to pay for this? Extremely few investors will have access to the capital needed while being willing to stomach the risk. Government support needs to be generous and sustained, not vacillate with shifting political winds.

And all this is just to replace existing use cases. It assumes no growth in demand, no long-term storage, no “hydrogen economy” to speak of.

Is this really the most promising idea we have?

Where will the high-value applications for electrosynthesis be?

While the focus for much of this article has been on green hydrogen, many of the issues it’s facing are also emblematic of electrochemistry as a whole: mediocre unit economics and poor fit with existing processes.

Electrochemistry isn’t a drop-in replacement for thermochemistry. To succeed, it needs to find applications where it can leverage its unique strengths and thrive in places where thermochemistry cannot.

The key to making a compelling economic case for decarbonization lies in creative approaches that can find other ways to add value.

Broadly speaking, I think this will involve 3 strategies, which will be elaborated upon in the sections that follow. They aren’t mutually exclusive—a winning technology may incorporate elements of multiple or all of them.

Embrace co-production

Every electrochemical cell has two (and usually three) components:

- A cathode which donates electrons to perform reduction reactions.

- An anode which withdraws electrons to perform oxidation reactions.

- Optionally, a separator, which physically prevents products from reaching the ones from the other electrode. A separator is often a good idea because in many cases the reduction products and oxidation products can react with each other and undo the hard work you put in to produce them.5

These days, reduction reactions like hydrogen evolution get all the glory. But let’s not forget about the other reaction. If it has to happen anyway, why not do something useful with it? The chloralkali process produces both hydrogen and chlorine at the electrodes. The chlorine gas is the primary product, but the hydrogen can be used for downstream products like hydrochloric acid.

The most commonly used electro-oxidation reaction is the oxygen evolution reaction, as it occurs in water and produces a relatively benign gas. The oxygen is usually viewed as a byproduct of the more value reduction reaction that’s simply vented, but in the right context it can provide economic value.

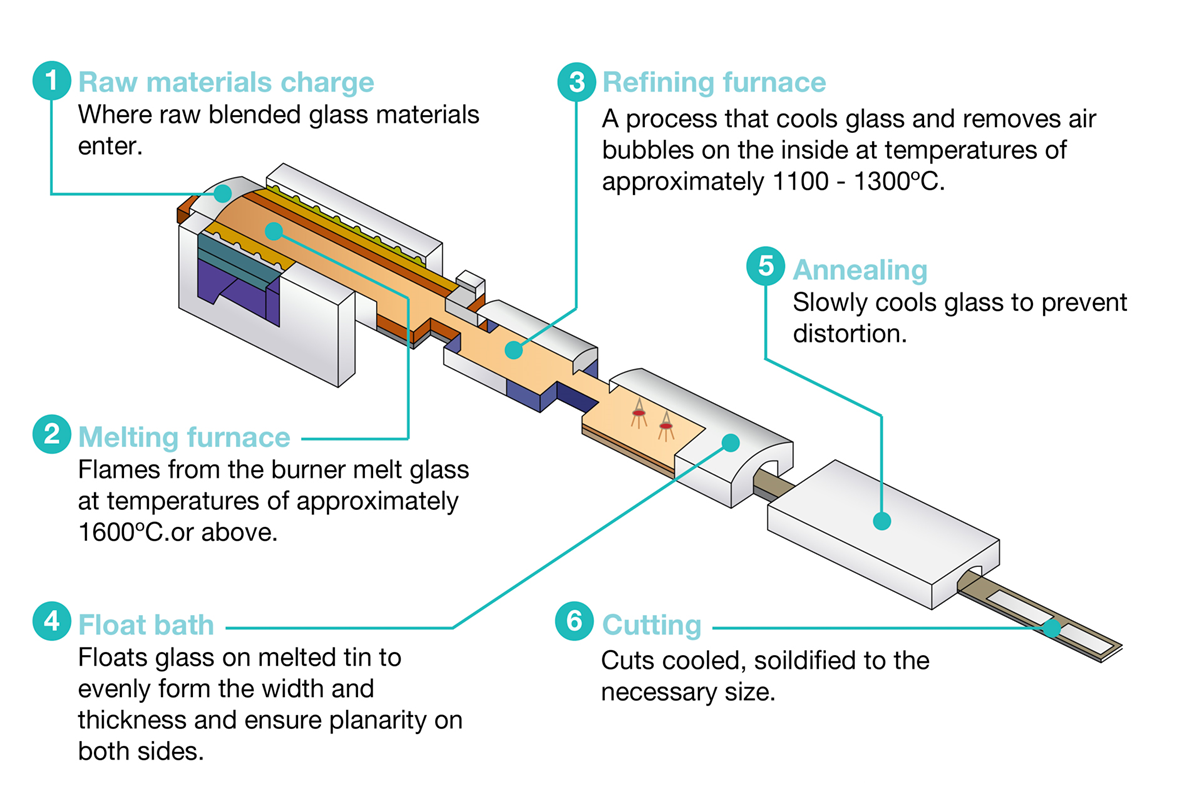

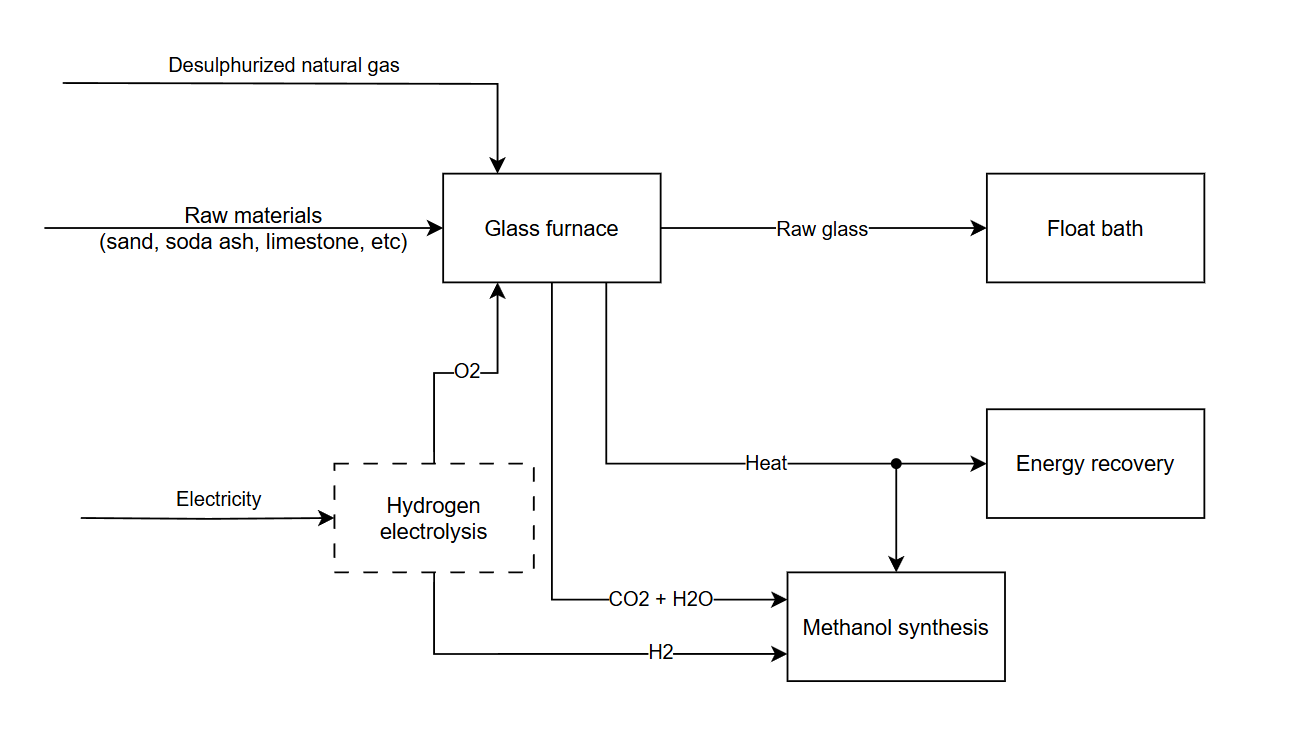

Consider the production of float glass. Glass melting furnaces require extremely high temperatures exceeding 1600°C which is challenging to achieve with air combustion. We could co-locate an electrolysis facility and feed the oxygen byproduct to an oxyfuel furnace, achieving much higher flame temperatures.

The furnace flue gas will be almost entirely water and CO2, which we can mix with the hydrogen to make methanol and subsequently plastics or resins. The furnace heat can be used, if required, to shift a water-gas equilibrium to achieve the optimal reactor feed composition.

This arrangement allows both processes to achieve better unit economics. It eliminates the oxygen generator on the glassmaking side, the compression train on the electrolysis side and the steam reformer on the methanol side. The natural gas desulphurization system and steam network are shared between glassmaking and methanol production. The furnace heat recovery system generates superheated steam which can be expanded through a turbine, significantly reducing grid electricity consumption.

I’m not claiming that the economics of this specific example will ultimately pencil out compared to e.g. simply electrifying the furnace. My point here is that even with the current disadvantages of water electrolysis, it isn’t immediately obvious—at least, to me—that this is a bad idea6. (At least, not any worse than using hydrogen for home heating.)

We also don’t need to limit ourselves to making oxygen. Many industrially useful reactions are oxidation reactions, such as VOC degradation in wastewater treatment, upcycling of waste plastics, aldehydes and ketones from alcohols, or olefins from alkanes. Oxygen evolution reaction (OER) alternatives remain a hugely understudied field and many of these reactions are poorly understood. There’s a lot of potentially low-hanging fruit here.

Radical process simplification

An interesting—if infrequently emphasized—property of electrochemistry is that the reduction and oxidation reactions are spatially7 and chemically separated. They occur on different catalysts and can use completely reactants and solvents, depending on the choice of separator.

This decoupling results in an inherent modularity: the reduction and oxidation reactions can, in principle, be mixed and matched to suit different needs. Electrolyzers, then, are actually 3 unit operations combined into one: a reduction step, an oxidation step and a separation step. Sometimes the electrolyte can even be selected so that the products phase separate from it!

This gives the designer a great deal of flexibility on the characteristics of their process: the inputs and outputs, power consumption, operating conditions and overall function.

This could potentially lead to cases where electrochemistry can delete steps—whether those are separations, reactions, or even simply heat exchanges. After all, an efficient process step is better than an inefficient process step. But even better than that is no process step.

Look for processes that have a large number of conditioning steps and/or reagents, and where side reactions, impurities, and limited single-pass yields have a significant impact on cost and complexity.

One prominent example is Boston Metal’s molten oxide electrolysis for refining iron ore. On top of replacing the blast furnace, it eliminates several other processing steps. The ore can directly be melted in the cell, so there’s no need for comminution (grinding). The impurities form a slag that doubles as the electrolyte in the cell, while the iron sinks to the bottom. There’s no coke added as a reducing agent, so a basic oxygen furnace treatment step isn’t required either.

Of course, ‘simple’ doesn’t mean easy—if anything, quite the opposite. Processes centered around electrochemistry will need to be redesigned from the ground up. A deep knowledge of the process they’re intended to replace will be needed. Scaling up will be tremendously challenging. There is an excruciating amount of detail that has to be nailed down for even ostensibly “simple” processes to work at large scales. In some respects, simple processes are even harder in this regard as there are less levers to pull when do problems inevitably arise. An exceptional amount of discipline will be needed to keep balance-of-system complexity under control.

The potential rewards, however, are enormous. A new, properly designed process might be able to fully take advantage of renewable electricity at bargain prices. A much simpler process could require significantly less capital despite the generally worse unit economics of electrochemistry. Such a process would be well-positioned to scale quickly and displace incumbents.

Make things that thermochemistry can’t

Before the Hall-Héroult process was invented, we had the Deville process for refining aluminum. This was a thermochemical process involving alumina (the oxide of aluminum), carbon dioxide, sodium metal and cryolite. It was significantly more expensive and complicated to operate:

- ~3.4 kilograms of sodium metal, a powerful but very expensive reducing agent, needed to be used for every kilogram of aluminum.

- It had to be done in a batched manner, making scaling up difficult.

- The reaction wasn’t self-sustaining, requiring complex external heating to maintain operation.

- The aluminum purity was generally worse than the Hall-Héroult process.

These factors made aluminum more expensive than gold despite being a relatively common element, effectively rendering it a non-factor for most applications. The now-ubiquitous electrolytic method was able to reduce the aluminum directly with electricity rather than sodium, used a simple reactor design, was self-heating, and could be operated in a continuous manner.

When you look around, you’ll find that the adoption of various materials and chemicals is closely tied to their ease of manufacturing and whether they are “good enough” for a specific application. The most commonly used plasticizer in PVC is diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), which is obtained from condensing phthalic anhydride with 2-ethylhexanol (2-EH).

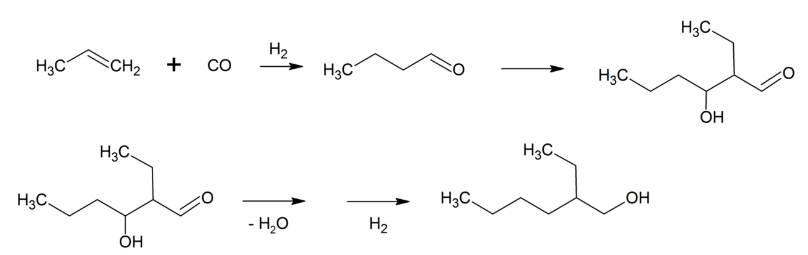

Why 2-ethylhexanol specifically? Over 2,500,000 tons are made per year. What’s so special about it? Why not 3-ethylhexanol, or 2-methylhexanol, or 2-ethylheptanol? It turns out that making 2-EH only requires propylene, carbon monoxide and hydrogen—all readily available from a crude oil feedstock—and can be done in just a few steps.

Some products are simply impossible or impractical to make at scale via thermochemical approaches for various reasons. Sometimes the required temperatures are too high, or the product yield is too low, or the molecular complexity is too high for elevated temperatures. Electrosynthesis, with its greater control over operating conditions and electron transfer, could make it feasible to synthesize better alternatives to the status quo.

Additional examples beyond aluminum include fluorinated compounds like PFOA and PFOS8, graphene nanosheets, specialty oxidants like perborates, and conductive polymers like polyaniline and polypyrrole9.

This is the most difficult approach. The nice thing about commodities is that finding a the product-market fit is trivial provided you can make something for the right price. This is different. It requires not only process development, but product & business development as well. Your product may be able do X better than product Y, but can you convince Y customers of this? There are many good reasons to stick to an existing solution with a proven supply chain rather than take a gamble on the hot new thing. Navigating this will require technical excellence, maintaining relationships and trust with commercial partners and considerable business acumen.

Success in electrosynthesis depends on eliminating the value gap

There’s a major line of thought that contends that carbon-neutral approaches are more expensive—because they can’t be anything else. Fossil fuel-based producers aren’t bearing the cost of their negative externalities. Decarbonization will inevitably result in some products and services becoming more expensive and that’s just something we’ll have to accept.

Believe me: I’m deeply sympathetic to this argument. It’s possible—even likely—that this will be the case.

But the truth is that nobody cares—least of all your customers. I wouldn’t be writing this article otherwise. Carbon pricing has been politically contentious almost everywhere it’s been implemented. Decarbonization efforts have become an ideological hot potato in the US largely for cultural reasons. The average person simply does not care that much about climate change. The median ‘green premium’ can be approximated as zero.

To make inroads, new technologies will have to compete in the most important arena: the balance sheet. Small incremental advances of current pathways are unlikely to get us there. To be clear, I do think modularization and mass production can help bring down costs. But to kick them off, we need to first reach the first “rungs” of product commercialization—we need to make sure we’re building the right thing. This is the key to initiating the virtuous cycle of learning-by-doing, further improvements and cost reductions, and more adoption.

To do so, we’ll need outside-of-the-box thinking to find promising-but-underinvestigated approaches. There’s no denying that this will be extremely difficult. But “extremely difficult” is infinitely more achievable then “impossible”.

Those are odds we’ll just have to take.

This goes both ways: an inability to decrease output can be just as problematic as an inability to increase it. While the latter is associated with renewables, the former includes many coal and nuclear plants. In both cases, inflexibility is a negative externality that must be compensated for elsewhere. ↩︎

This is one of those aphorisms that seems completely self-evident to the point of unhelpful banality. But in my experience, it’s horrifically true, and actually very difficult to consistently implement. ↩︎

Within reasonable limits. ↩︎

Modularization for complex industrial projects is a fascinating and very complex topic, and I hope to discuss it in detail in a separate post at some point. ↩︎

This can also lead to heat being generated in an uncontrolled manner, which is considered very bad for running a safe and reliable operation. ↩︎

And if you have a better idea, you should let them know. The glass industry is desperate for good solutions to decarbonize. ↩︎

And sometimes temporally as well. ↩︎

Admittedly, perhaps not the best example given what we know now… ↩︎

I have some more ideas, if anyone’s interested. Feel free to reach out. ↩︎