Do We Need Better Hydrogen Catalysts?

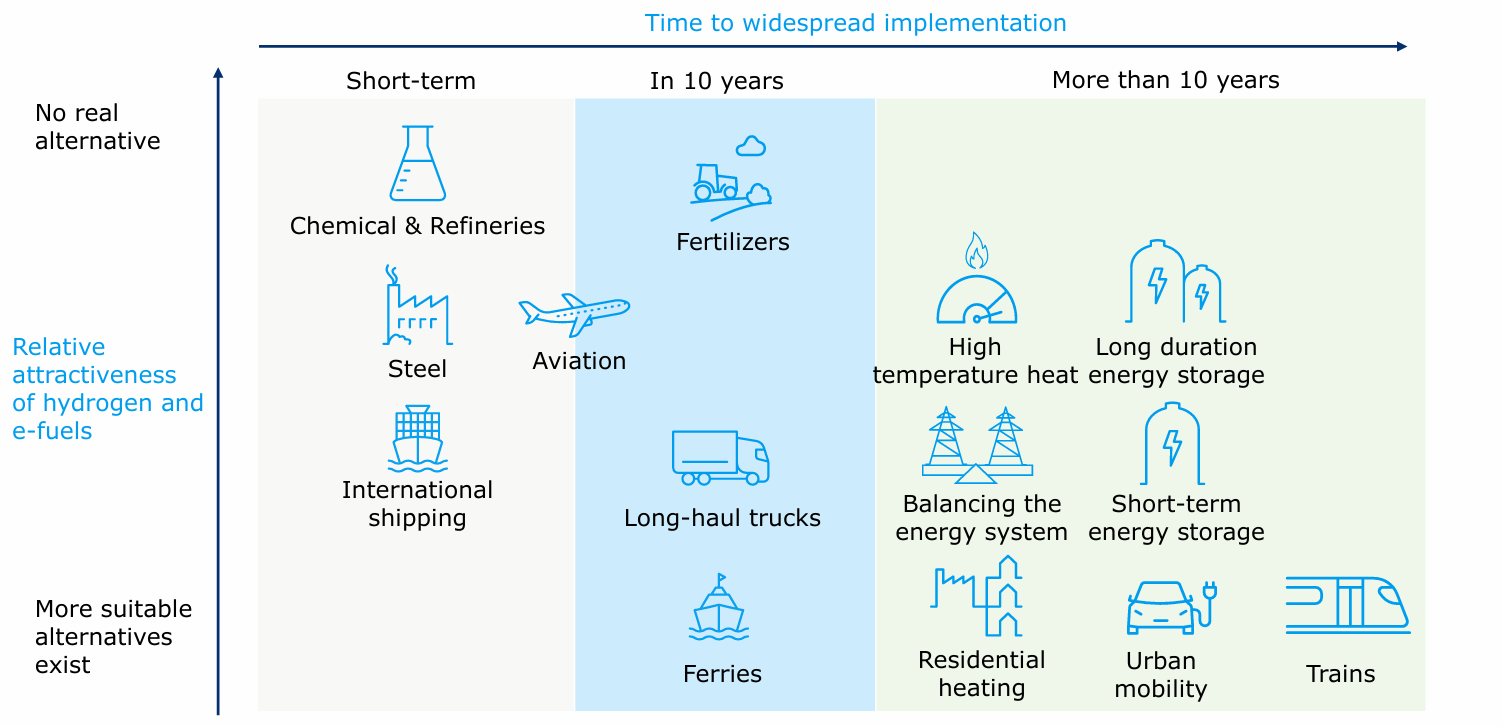

Renewable energy technology is a tale of two trajectories. Over the past decade, we’ve seen dramatic cost reductions for solar power, wind power, and batteries stemming from a mixture of technological improvements, economies of scale and learning effects. This is all great news for decarbonization, yet a few key pieces are still missing1. Critically, we need a form of cheap, scalable, long-term energy storage, a means of decarbonizing heavy industry and chemical synthesis, and a form of chemical energy for long-haul transportation where batteries will likely be impractical for the foreseeable future. Is green hydrogen the solution?

At least in principle, green hydrogen—hydrogen produced from renewable electricity—would be suitable for all three of these, killing multiple birds with one stone. There’s one problem: silver bullets are expensive, and so is green hydrogen.

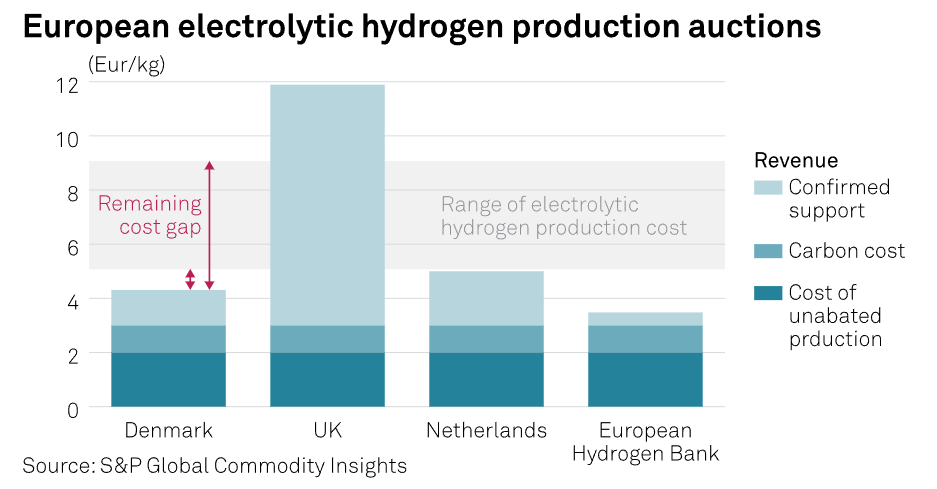

Recent green hydrogen auctions in Europe have attracted bids of \$4-12/kg, with firms are targeting an “eventual” price of \$2-3/kg. As I’ve previously noted, even this is still probably far higher than the effective prices paid for fossil-derived hydrogen which can be under \$1/kg.

In general, despite much investment and R&D, costs have not dropped as much was hoped. The most recent EU Hydrogen Bank auction attracted record low bids of \$3.50/kg, but many observers are skeptical about the feasibility of this price point.

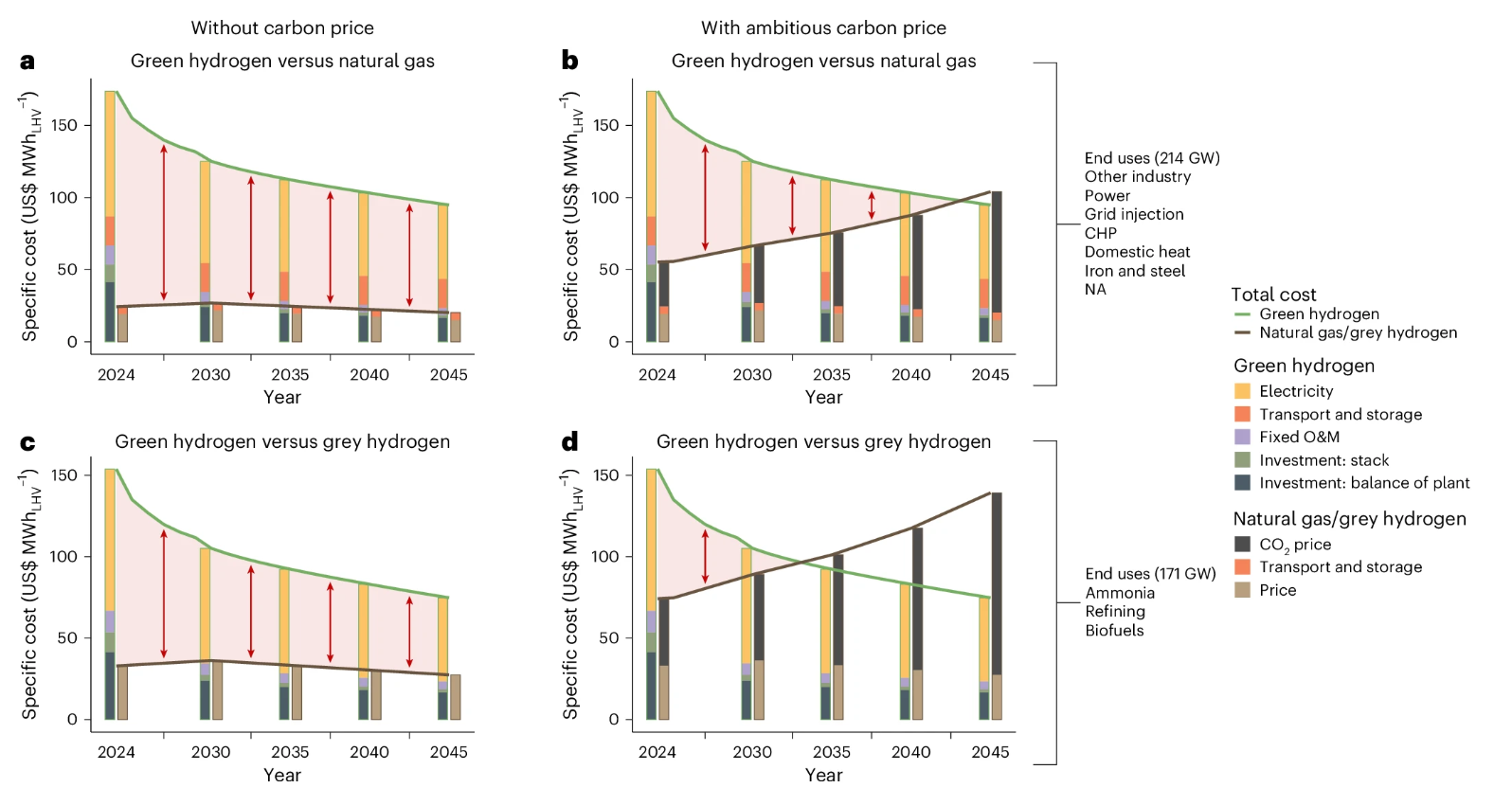

To make green hydrogen competitive with fossil fuels, one paper has to assume a scenario where carbon taxes rise to over \$400 per ton of CO2 by 2050! That’s a point where direct air capture starts to look economically appealing, which I think speaks for itself.

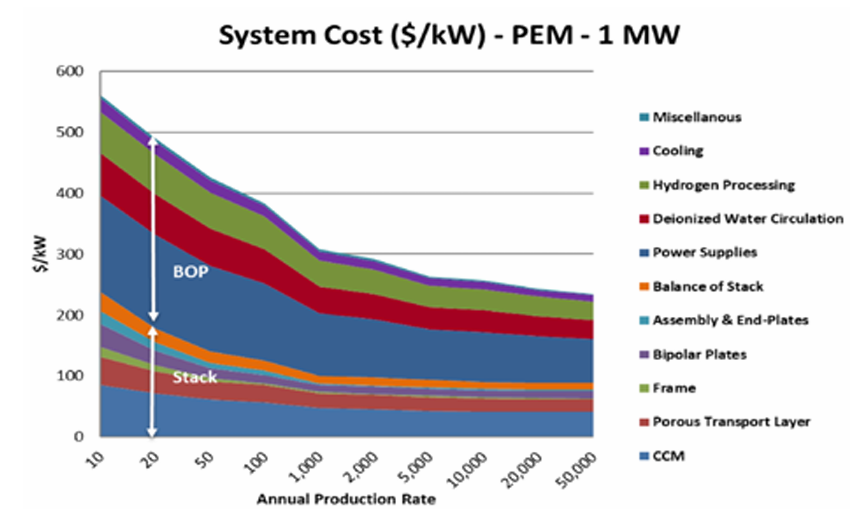

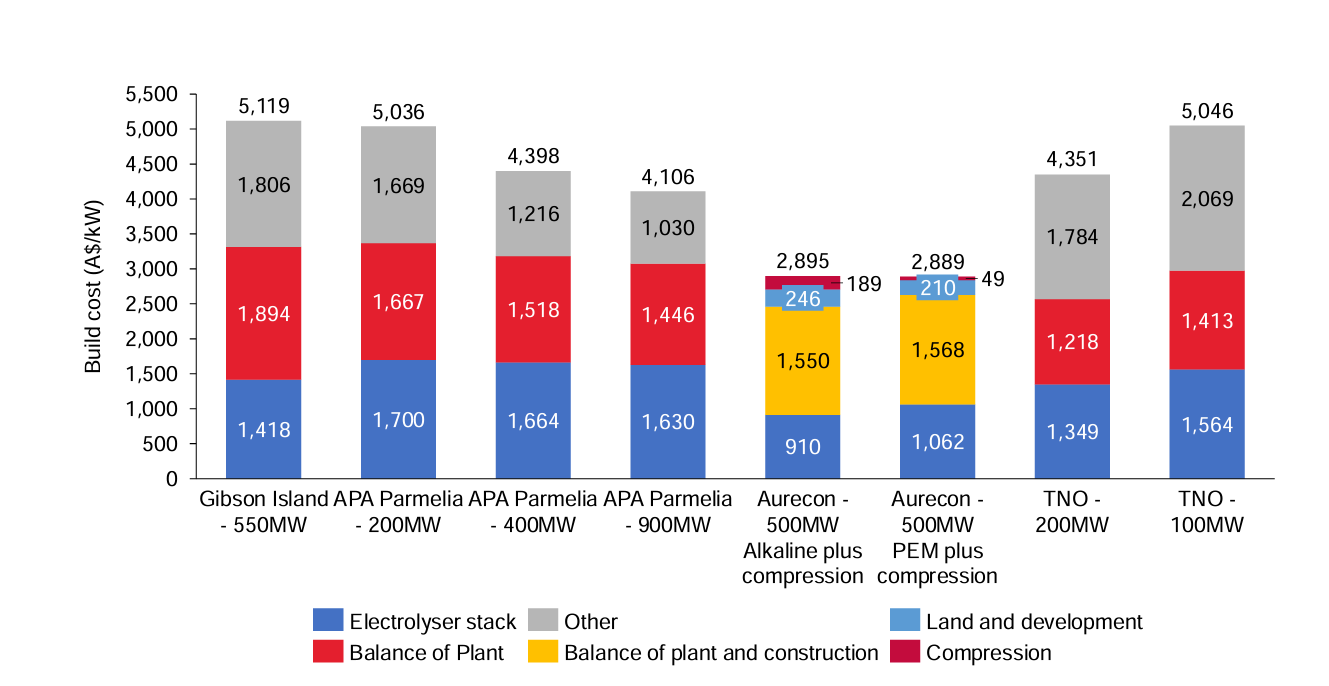

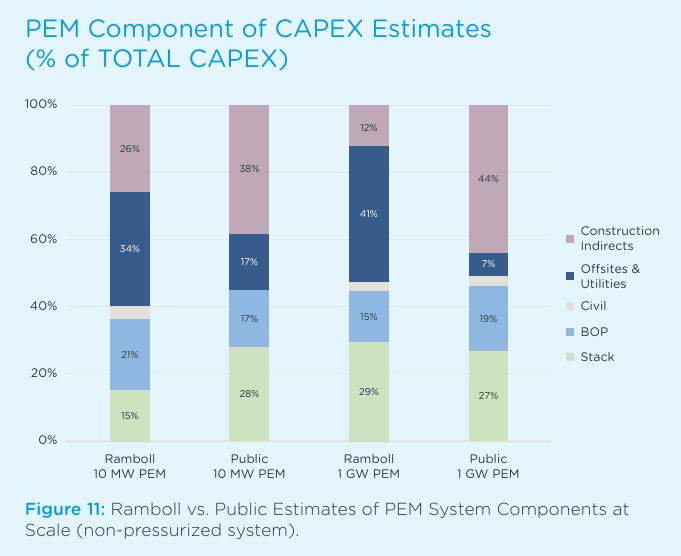

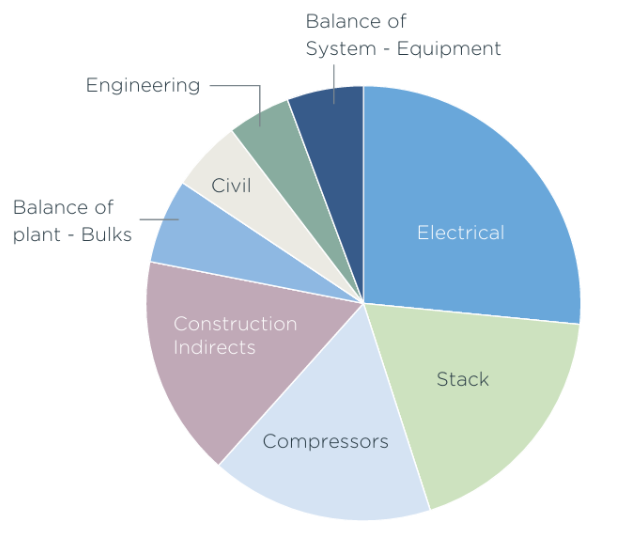

What’s driving this cost? Roughly half to two-thirds of it is electricity and other operating costs, while the rest is from the amortized capital costs of building the plant. For green hydrogen to be cost-competitive, the total plant likely can’t cost much more than \$1,000/kW.

What goes into building a green hydrogen plant? There have been many studies on this; a particularly influential one is a 2020 International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) report, which predicted that large-scale deployment and learning curve effects would lead to significant cost reductions. They projected that green hydrogen plant capital costs would quickly drop to below \$1,000/kW in the near term and less than \$200/kW in 2050.

Unfortunately, 5 years later, it’s clear that was far too optimistic. Actual realized costs in real-world projects ended up being 2x-3x higher, at \$2,000-\$3,000/kW.

To be fair, cost estimation for new technologies and processes is extremely challenging. Cost overruns and a failure to anticipate the true scope of work are a fact of life for large-scale industrial projects. Even a +100% underestimate—while not a good outcome per se—isn’t particularly unusual, especially for a first-of-a-kind (FOAK) build. But it does indicate that something about the initial assumptions was terribly wrong, and that future estimates need to be recalibrated accordingly. That happened in 2024, when BNEF adjusted their cost predictions for green hydrogen and found that it was unlikely to beat grey hydrogen anywhere for the foreseeable future.

So that leaves us in our current predicament. Green hydrogen will almost certainly be needed for decarbonization, and it will be needed in very large quantities. But to be economically competitive with natural gas-fueled steam reforming, production costs need to drop by 50-75%, and perhaps even more. The path to getting there isn’t clear. What is to be done?

If your newsfeed looks anything like mine (a huge nerd who reads a bunch of cleantech articles), you’ll probably be bombarded with constant press releases and puff pieces about new and improved catalysts for hydrogen production.

This feeds into a popular perception that the need for better catalysts is major roadblock for the commercial viability of hydrogen. Is this true? In this post, I’ll review and assess the potential impact of four of the biggest green hydrogen catalyst research programs:

- Hydrogen electrocatalysts

- Oxygen electrocatalysts

- Seawater electrocatalysts

- Solar-to-hydrogen photocatalysts

Would a breakthrough in any of these rescue the economics of green hydrogen? Spoiler: the answer is no.

What do electrocatalysts do?

First, a technical primer. If you’re already up to speed on the basics of hydrogen electrochemistry, feel free to skip this section.

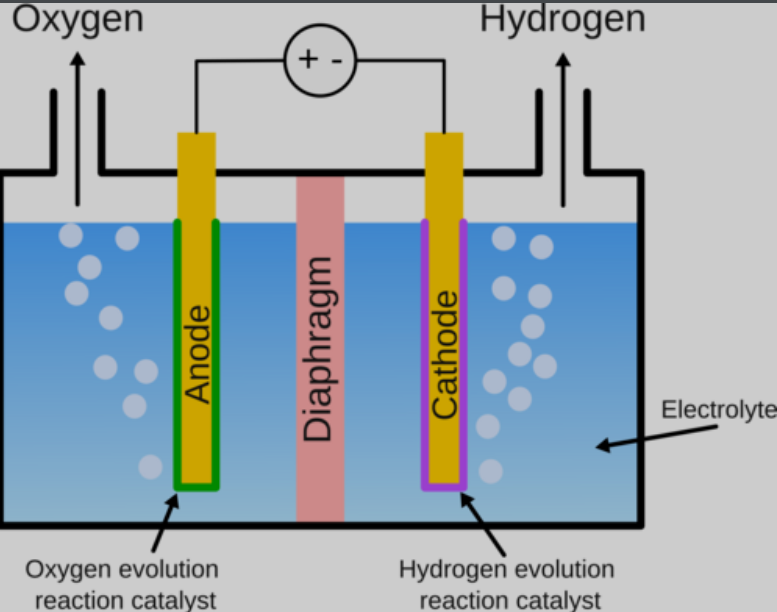

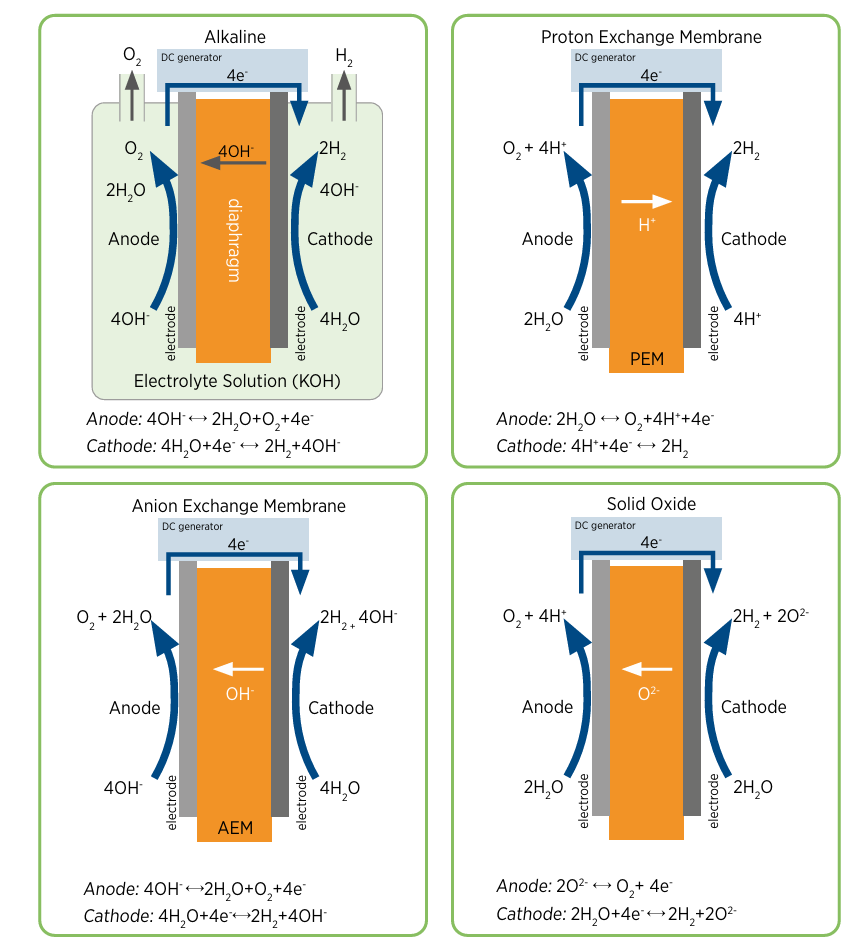

A hydrogen electrolyzer uses electricity to turn water into hydrogen and oxygen, a process known as water splitting. The core of an electrolyzer is an electrochemical cell, which has two electrodes: the negative cathode and the positive anode. Hydrogen is produced at the cathode in a reduction (electron accepting) reaction. For example, in an alkaline environment the reaction would be: $$ \ce{2H2O + 2e- -> H2 + 2OH-} $$ In the scientific literature this reaction is often called the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER).

To complete the electrical circuit, every electrochemical cell needs to pair a reduction (electron receiving) reaction with an oxidation (electron donating) reaction. The most commonly used one is the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), as it only requires water and produces a relatively benign gas. Assuming an alkaline environment once again, the reaction is: $$ \ce{4OH- -> O2 + 2H2O + 4e-} $$ Notice how the HER consumes electrons and water and produces hydroxide ions (OH-) while the OER consumes hydroxide ions and regenerates water and electrons. So the net result of the combined reactions is the production of hydrogen and oxygen.

It’s important to build or coat the electrode with a material that catalyzes the HER, which occurs at the electrode surface, to improve the performance of the cell.

Electrocatalysts work a little differently than catalysts for “conventional” chemical reactions where a bunch of reagents are mixed together and spontaneously form products. In the latter, the catalysts speed up the reaction, so a reaction that might take hours to convert all the products might only take minutes or seconds.

In electrochemistry, the reaction rate is determined by the rate of charge transfer; that is, the supply of electrons. Therefore, the production rate of hydrogen is directly proportional to the electrical current being fed to the cell. What do catalysts do, then?

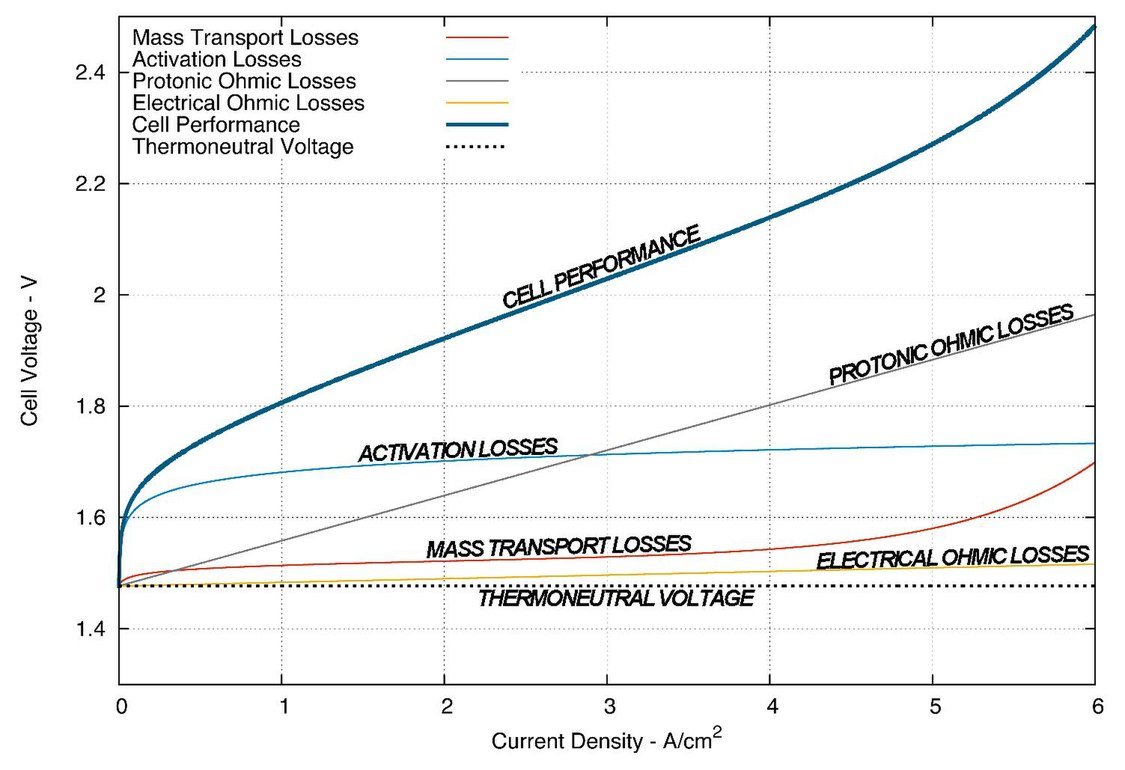

From an electrical perspective, electrochemical cells are very unusual loads. Every electrochemical redox reaction has a reduction potential, which is thermodynamically the minimum voltage required to drive the reaction forward. If the voltage applied to the cell is below this threshold, no current will flow. Increase the voltage beyond it, and a current will appear and subsequently increase2—although the response is strongly nonlinear.

An electrocatalyst reduces the voltage needed to achieve a specific current density; therefore it improves the energy efficiency of the cell since $\text{energy} = \text{voltage}\times\text{current}\times\text{time}$, but hydrogen production is proportional to $\text{current}\times\text{time}$. In the technical literature, the electrolyzer current is usually expressed in current density—current per unit electrode active area—so that the performance of electrolyzers of different sizes can be compared in an apples-to-apples manner.

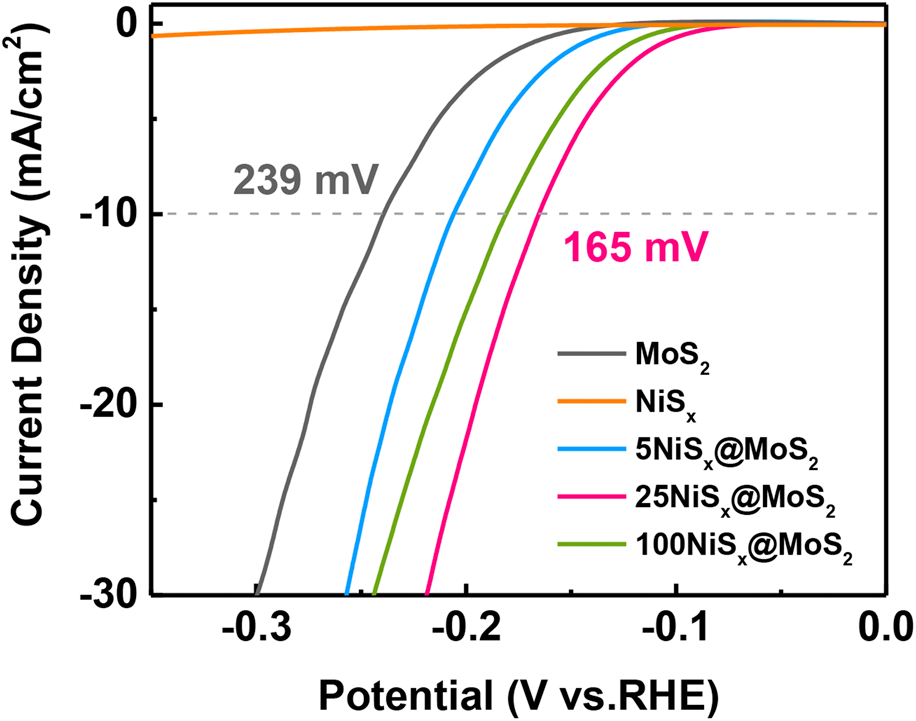

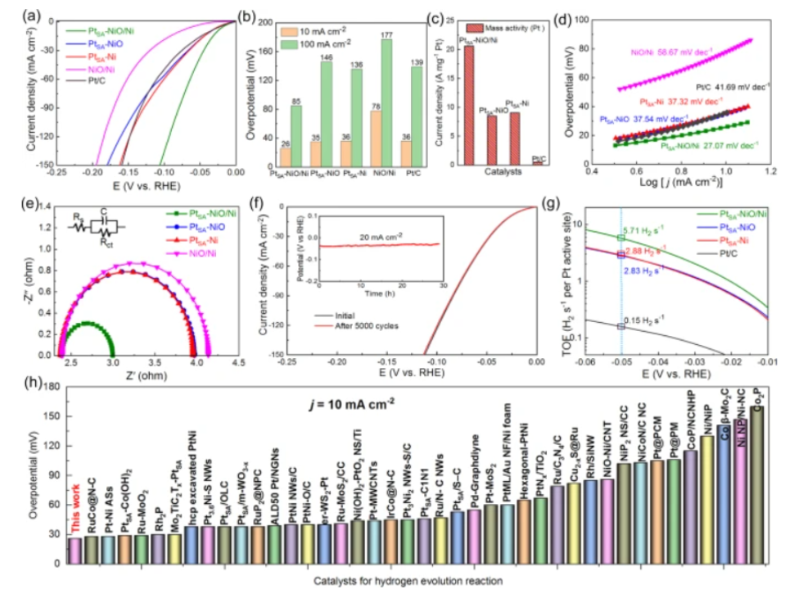

The electrode potential is usually provided on a relative scale, using the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) as a comparison point. The RHE is an “ideal” electrode that represents the minimum potential required for the hydrogen evolution reaction to occur. The additional voltage required to achieve a given amount of current is called the overpotential. Two common benchmarks are the overpotential required to reach a current density of 10 mA/cm2, and the overpotential required to trigger the onset of current called the activation overpotential. An overpotential of 0 volts represents an energy efficiency of 100%3.

The operating cell voltage is a tradeoff between energy efficiency and production rate, and consequently is a tradeoff between operating costs and capital costs. A more efficient cell requires a lower voltage to achieve the same current than a less efficient cell, which means it can produce the same amount of hydrogen using less electricity. Alternatively, it could operate at the same voltage but at a higher current, which allows it to achieve a higher productivity at the same energy efficiency.

As a side note, there’s another performance metric called the Faradaic efficiency, which is a measure of reaction selectivity. It’s primarily used when there are multiple possible products that can be made, such as in electrochemical CO2 reduction. In hydrogen electrolysis, the side reactions are usually negligible and the Faradaic efficiency is over 99.9%, so it’s rarely discussed4.

The upshot is that hydrogen electrocatalyst development boils down to finding new materials that are ideally:

- Chemically stable

- Cheap

- Achieve low overpotentials

There are two major types of hydrogen electrolyzers that are commercially available:

- Alkaline water electrolyzers (AWEs) which operate, as the name suggests, under alkaline conditions.

- Proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers (PEMWEs) which operate in neutral-to-acidic conditions.

- Other technologies, such as solid oxide electrolyzers (SOECs) or anion exchange membrane electrolyzers (AEMWEs) which aren’t as mature or scalable. I won’t be discussing them much.

AW electrolyzers have been around for over a century, while PEM electrolyzers are a more recent development. For a variety of technical reasons, PEMWEs have many operational advantages over AWEs: they are much lighter and more compact, often by an order of magnitude or more, and have the ability to ramp up and down very quickly5. However, the harsher operating conditions mean PEMWEs commonly use platinum-based hydrogen catalysts, compared to the much cheaper nickel-based catalysts found in AWEs.

As everyone knows, platinum is a very valuable metal, so surely it must be driving up the cost of hydrogen? Unfortunately, this isn’t really correct.

Hydrogen catalysts are a solved problem

The hydrogen evolution reaction has been essentially a solved problem for decades. There are practical, cost-effective, and efficient options available. The portion of the production cost attributable to the hydrogen catalyst is essentially negligible.

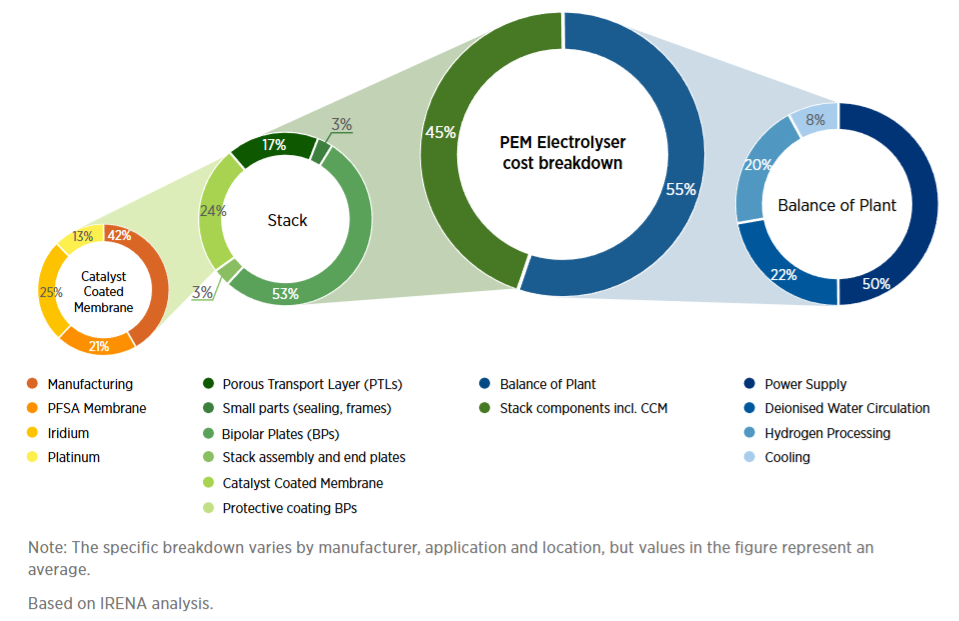

Let’s put this into perspective: if someone suddenly invented a new HER catalyst that was made of dirt and as performant as platinum (one of the best HER catalysts), it would be heralded—and rightly so—as a scientific breakthrough. But the economic impact would be immaterial. According to the aforementioned IRENA report, platinum is itself around 3% of the cost of the stack.

We know, however, that IRENA’s report underestimated the costs of the rest of the plant. A recent study from the engineering consulting firm Ramboll, using real-world data, found that PEM electrolyzer stacks are less than 30% of the capital cost of a large plant.

Readjusting the catalysts costs to reflect this means a virtually free catalyst, ceteris paribus, would reduce the plant CAPEX by around 1% and have a negligible effect on OPEX.

Electrode overpotentials, meanwhile, are less than 100 mV for top-performing catalysts which represents an energy efficiency of 92-94%. If we take into consideration all system-wide energy losses, and not just the electrolyzer stack, a 100 mV overpotential represents an energy loss of about 5%. The very best performing catalysts in the lab have overpotentials of less than 30 mV, which is 98% efficient! Impressive as this is, it also sets a ceiling on potential improvements.

While it’s always possible to make a case for further investigation, the HER is, relatively speaking, a solved problem. We have commercially available HER catalysts for a broad range of use cases. The state-of-the-art is approaching thermodynamic limits.

That’s not to say that more studies would be completely useless. There are avenues of investigation that are still worth exploring because they could result in useful advances in other fields or can help de-risk commercial scaleup: e.g. work degradation mechanisms or deposition methods.

There’s nothing wrong with incremental progress, and it’s a necessary part of commercializing promising technologies. But we also have to consider the potential upside and it’s safe to say that any further gains would likely be at best marginal. The best case for a future hydrogen catalyst is that it reduces energy consumption by ~5% and capital costs by 1%.

Does that seem like a compelling case for further research investment?

Oxygen catalysts: scientifically interesting, but few practical forthcoming solutions

Between the hydrogen evolution reaction and the oxygen evolution reaction, the former receives the lion’s share of attention in popular media. This is also true—although admittedly to a lesser extent—in academia, where much research funding for electrochemistry goes towards the development of better HER catalysts.

Despite this, the OER is far more interesting from both a scientific and industry perspective6. OER catalysts, scientifically speaking, are kind of in the opposite situation of HER catalysts. The state-of-the-art performance is “decent”, although not fantastic, and in certain respects a breakthrough OER catalyst would be genuinely useful.

This is in large part due to the fundamental physics of oxidation. Under an oxidative potential, the materials in the anode tend to become positively charged (become cationic). Conventional current flows from positive charge to negative, so negatively charged electrons need to jump from the electrolyte to the electrode to maintain the current in the electrochemical cell. But the net flow of charge can equally be maintained by having positive charge jump from the electrode into the electrolyte. This positive charge is provided by cations of…electrode, effectively dissolving it over time.7

Because of this, electrode durability and stability is much more challenging for the OER than it is for the HER. The difficulty primarily depends on the pH of the electrolyte; stability becomes exponentially harder with higher acidity.

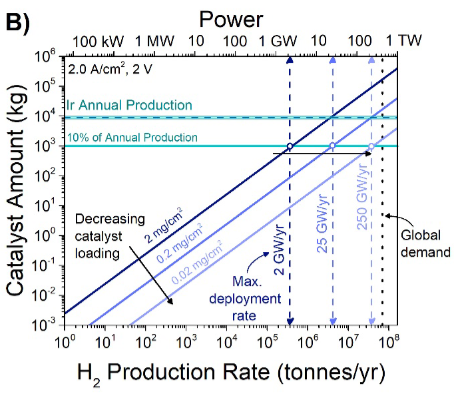

The only viable catalyst at commercial scales for the OER under acidic conditions8 is iridium oxide. Iridium is one of the rarest and most expensive naturally occurring metals in the world: worldwide production is approximately 7 tons per year—for comparison, annual platinum production is around 200 tons, and annual gold production around 2,000 tons.

In a PEM stack, iridium accounts for a larger portion of the manufacturing cost relative to platinum—around 6%. This is a little misleading, however, because PEM electrolyzers aren’t currently being produced in decarbonization-relevant volumes. If manufacturing was scaled up, the demand for iridium would quickly exceed available supply and the price would skyrocket.

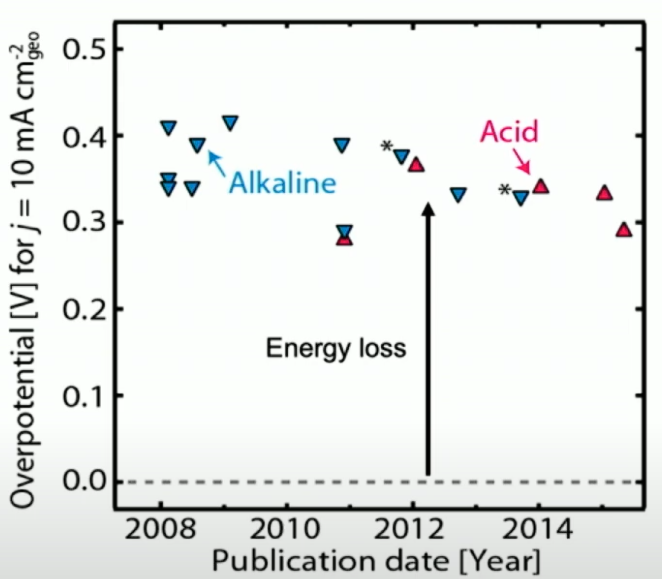

Ironically, iridium isn’t even that amazing of a catalyst! It’s good, but not great. Energy losses from OER are easily 3-4x that of the HER.

Why can’t we simply develop non-iridium catalysts, then? We have tried—and failed. Despite scouring the periodic table across decades of R&D, other materials have so far had unacceptable trade-offs in performance, cost, or stability. Some funding agencies, such as the US Department of Energy, have effectively abandoned efforts to find viable alternatives9 and are instead focusing on finding ways to reduce the iridium loading on PEM anodes—essentially finding ways to make the iridium catalyst layer thinner with new fabrication techniques and coating formulations.

This isn’t a showstopper for green hydrogen: AW electrolyzers or AEM electrolyzers operate in alkaline environments and don’t need iridium catalysts. Of course, these have their own respective weaknesses and tradeoffs. It’s still unclear which designs will prove to be superior in the long run—but the point is that there are solutions beyond simply developing better catalysts.

There’s another problem beyond stability issues. Vanishingly few catalysts have been able to achieve overpotentials of less than ~300 mV at meaningful geometric current densities10, which translates to an energy efficiency of roughly 75-80%.

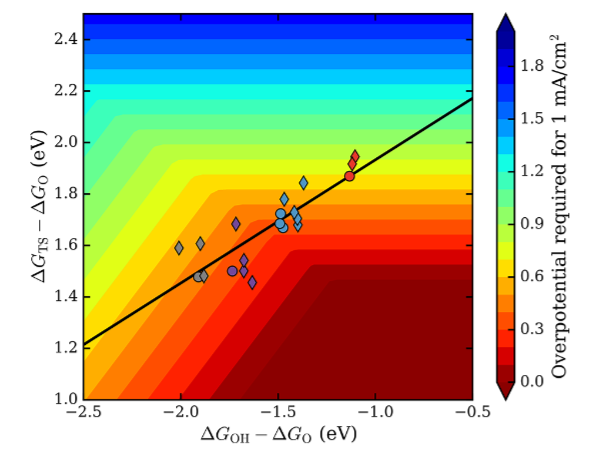

This lack of progress suggests that there’s some fundamental limit preventing us from achieving better performance. Rather than freely exploring the design space, we’re just moving on a constrained path embedded in some higher-dimensional surface.

Theoretical and computational developments starting in the mid-2000s have revealed that this is indeed the case. Heterogeneous catalysts are subject to what are called linear scaling relations, which impose fundamental limits on their performance. In essence, the binding energies of reaction intermediates are intrinsically mathematically linked, and at the limit improving one reaction step inevitably makes another one worse. Importantly, this is independent of the materials used in the catalyst. A detailed explanation is rather technical and beyond the scope of this post, but the point is that the OER is a prime example of a reaction that’s butting up against these limits11.

So in theory, better OER catalysts could be genuinely beneficial, improving not just hydrogen electrolyzers but also any other electrochemical cell that requires an oxidation reaction under ambient conditions. But in practice, we’ve made little progress and there’s good reason to believe a breakthrough is out of reach.

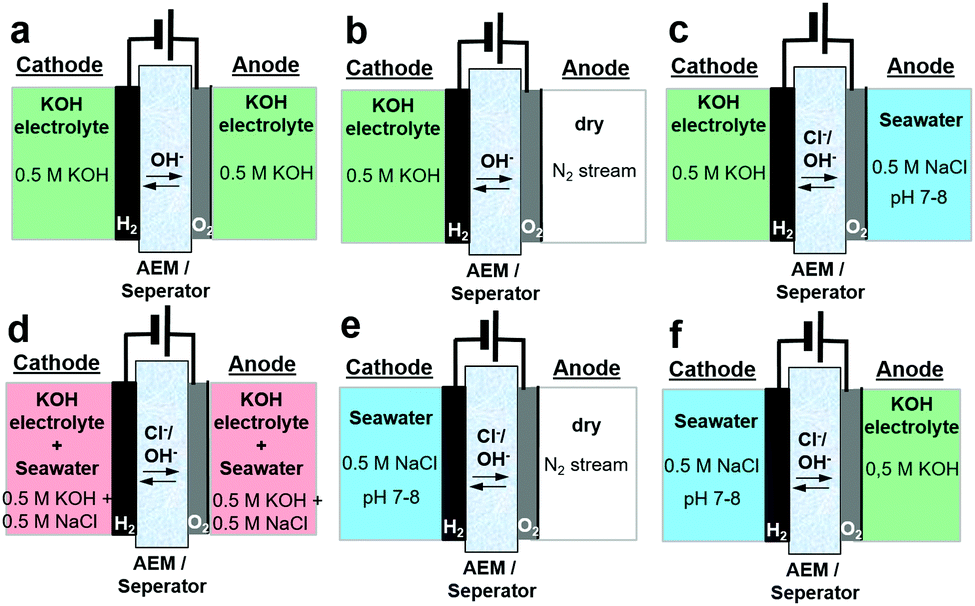

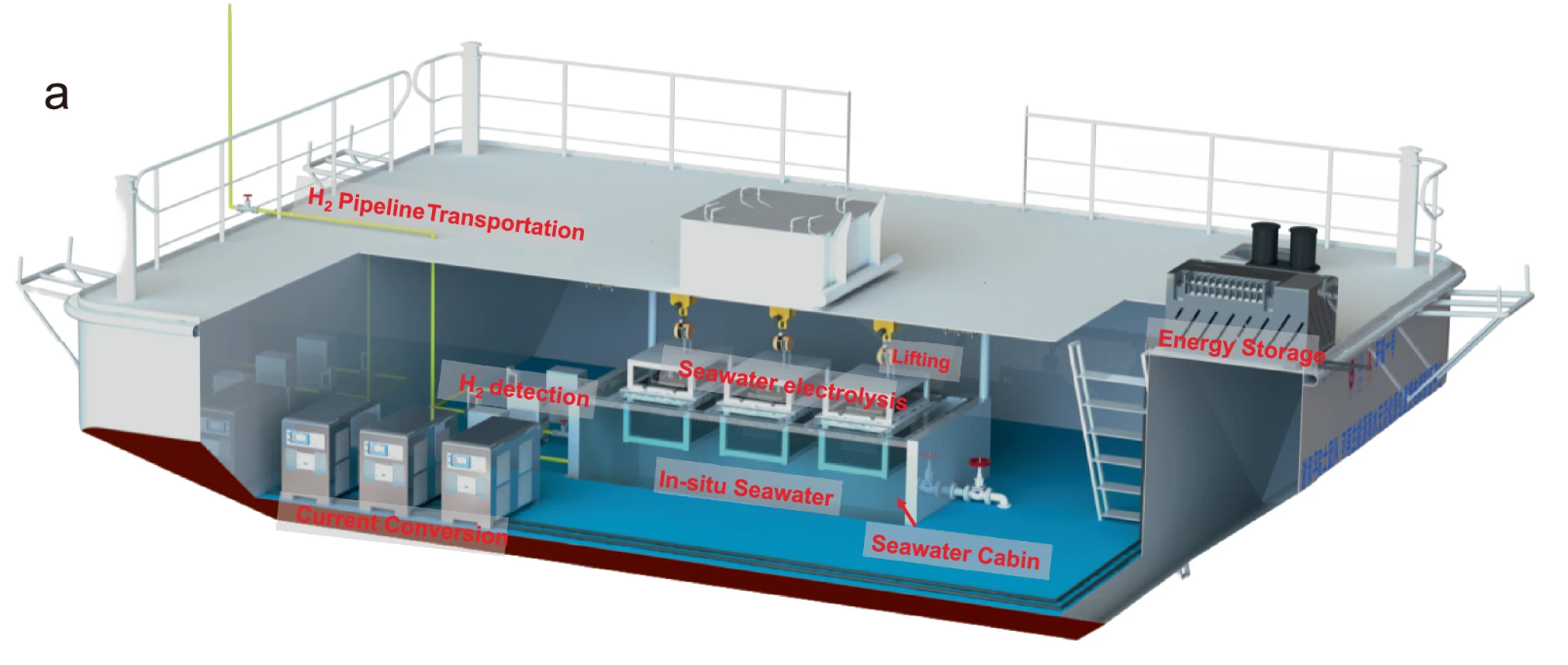

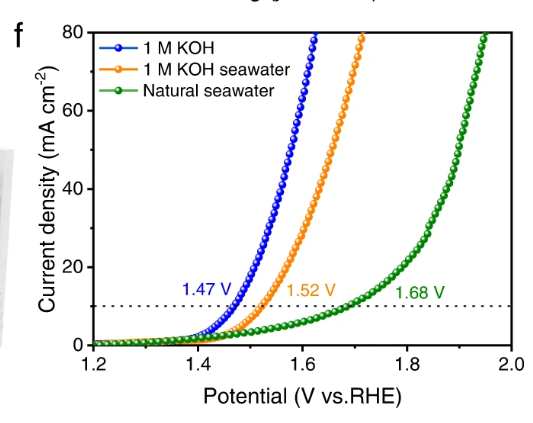

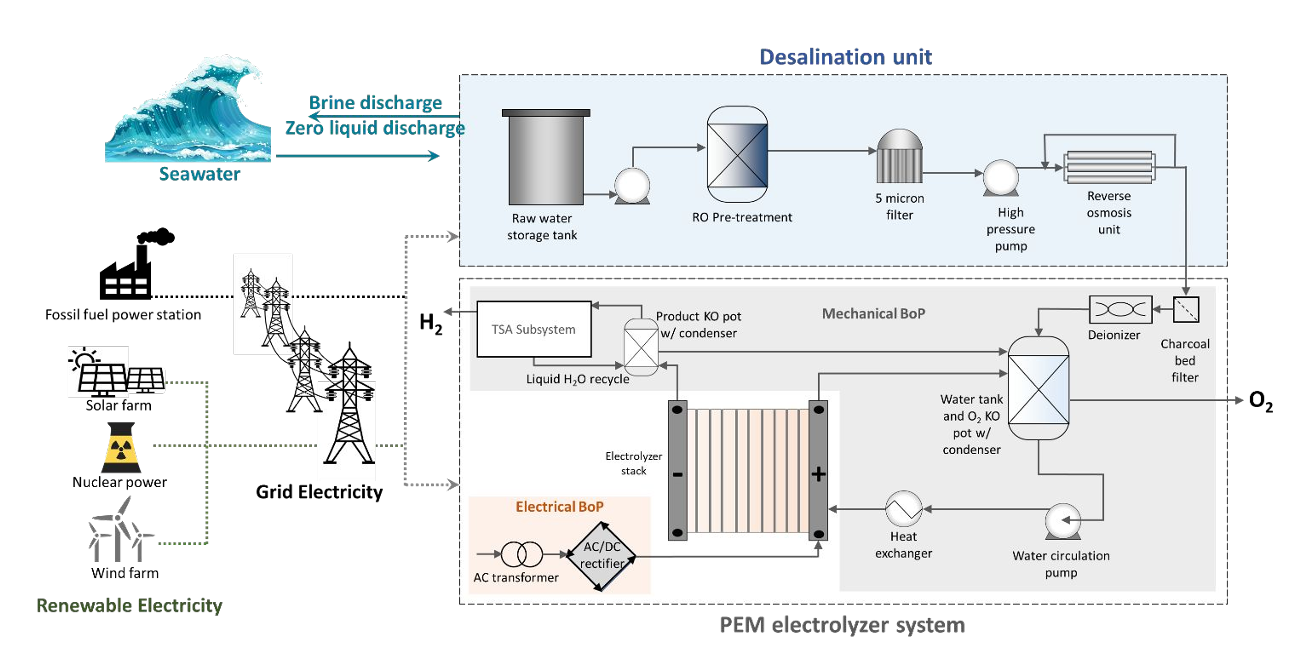

Seawater electrolysis: a non-solution to a non-problem

This is such a stupid idea that I’m baffled by how it ever got any sort of momentum.

Let’s start by contextualizing the problem: the hydrogen from green hydrogen comes from water. Naturally, a large hydrogen plant will consume a fair amount of water. Making a kilogram of hydrogen requires roughly 9 kilograms of water. On top of that, this water has stringent purity requirements, as impurities can irreversibly degrade the electrolyzers through a variety of mechanisms, such as scaling or catalyst poisoning. Alkaline water electrolyzers typically use reverse osmosis (RO) treated water, and PEM electrolyzers are even more stringent, requiring deionized (DI) water.12

Even more water is needed for cooling. Every kilogram of hydrogen produced can generate enough heat to evaporate up to 20 kilograms of water!

Rather than using valuable freshwater, the reasoning goes, we could instead design robust catalysts that can make hydrogen directly from seawater, a natural and abundant electrolyte. Seems like a win-win!

Many experiments and pilot-scale projects have been undertaken. One particularly futuristic vision, often accompanied by renders, is of offshore platforms producing hydrogen using wind power and transmitting the hydrogen back to the shore using undersea pipelines.

At first glance, it might seem like a reasonable idea, but even a cursory analysis shows how silly it is.

On the engineering side, seawater electrolysis comes with a myriad of new problems. The environment is now much harsher, and all of your processing equipment—not just the electrolyzer—needs to be constructed of more expensive corrosion-resistant materials. Performance is inherently worse: while seawater is conductive, it’s not nearly as conductive as the electrolytes typically used in alkaline electrolysis, resulting in lower efficiencies.

Other problems include:

- Having to operate catalysts in a optimal regime and needing to compromise between performance and stability.

- A risk of making chlorine gas instead of oxygen if anode potentials are too high.

- Scaling and precipitation of minerals, such as calcium salts.

- Electrode and membrane fouling from bacterial & algae growth.

- Poor control over operational conditions due to the inherent unpredictability of the feedstock.

But even if all of these issues could be solved, the proposition just doesn’t make any economic sense! In return for making everything more complex, expensive, dangerous, and failure-prone, you get to take an extremely cheap feedstock—water—and make it… cheaper? Why would you do this?

Consider the alternative option: if your plant is located on the coast and you have ample access to low-cost electricity, you could simply build a desalination system to supply your water needs. The most efficient desalination plants in the world have a freshwater production cost of less than \$0.50/m3, and the energy for desalination is approximately 0.15% of the amount needed for electrolysis.

Admittedly, some additional processing beyond drinking water purity is needed to make it suitable for hydrogen production. For the sake of argument, let’s assume we have an egregiously inefficient setup and that our water treatment cost is 50 times higher, or about \$25/m3. That would increase our production cost by ~$0.25/kg H2.

Is that a non-negligible number? Sure. Are there bigger fish to fry? Yes. Could we simply also assume a markup that’s less than 50x? You bet!

Seawater electrolysis belies a complete ignorance of engineering design principles or any of the techno-economic realities of green hydrogen.

Solar-to-hydrogen: the cure is worse than the disease

An electrochemical stack needs DC electricity to function, provided at a specific voltage and current. If using AC electricity from the power grid, this requires a lot of expensive and complex power electronics. Electrical balance of system is a significant and often underestimated portion of plant CAPEX and can exceed the cost of the stacks themselves.

One solution to this are solar-to-hydrogen technologies, which use sunlight to directly make hydrogen rather than generating electricity as an intermediate step, avoiding all the electrical conversion and transmission.

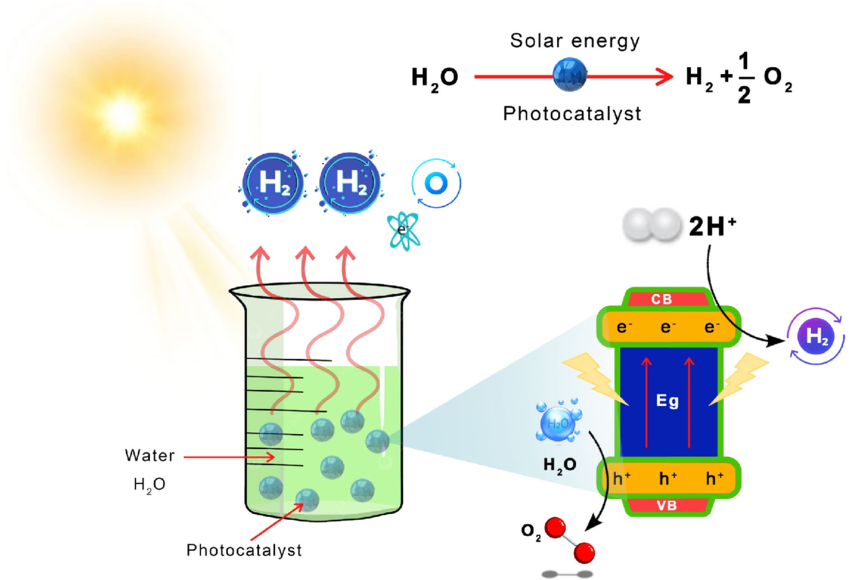

There are too many possible approaches to cover them all in detail. Two of the most common techniques are called photocatalysis (PC) and photoelectrocatalysis (PEC). Conceptually, they’re very similar. PC uses photoreactive particles suspended in water that absorb incident photons and use the energy to directly split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

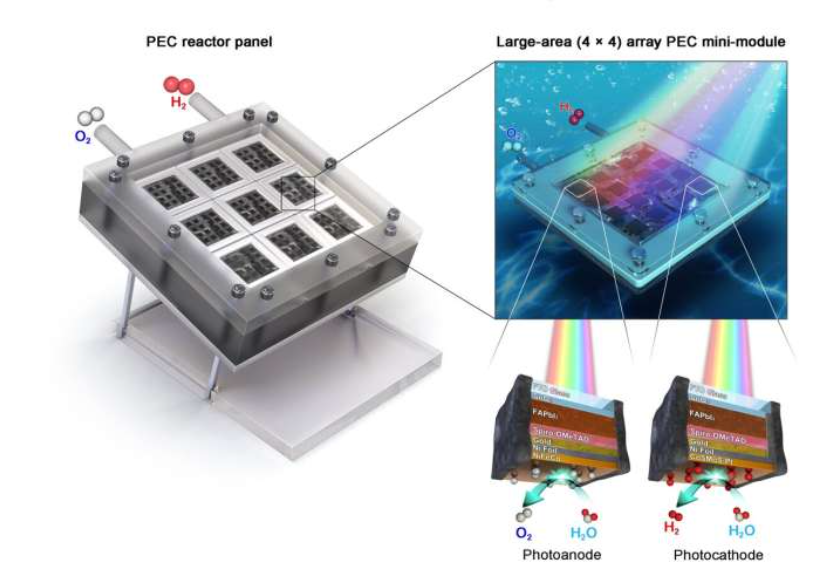

PEC also uses photoreactive materials but uses them like electrodes in a traditional electrochemical cell. Hydrogen and oxygen production occur on separate, electrically bonded electrodes. While PC is simpler, PEC is generally more performant as the two electrodes can be optimized separately.

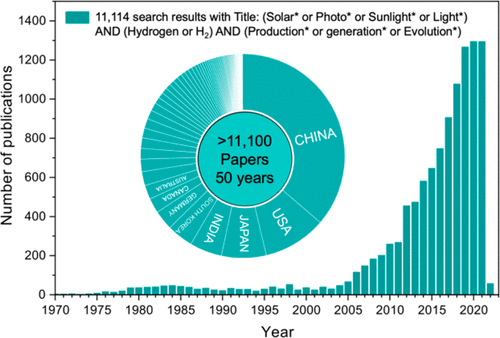

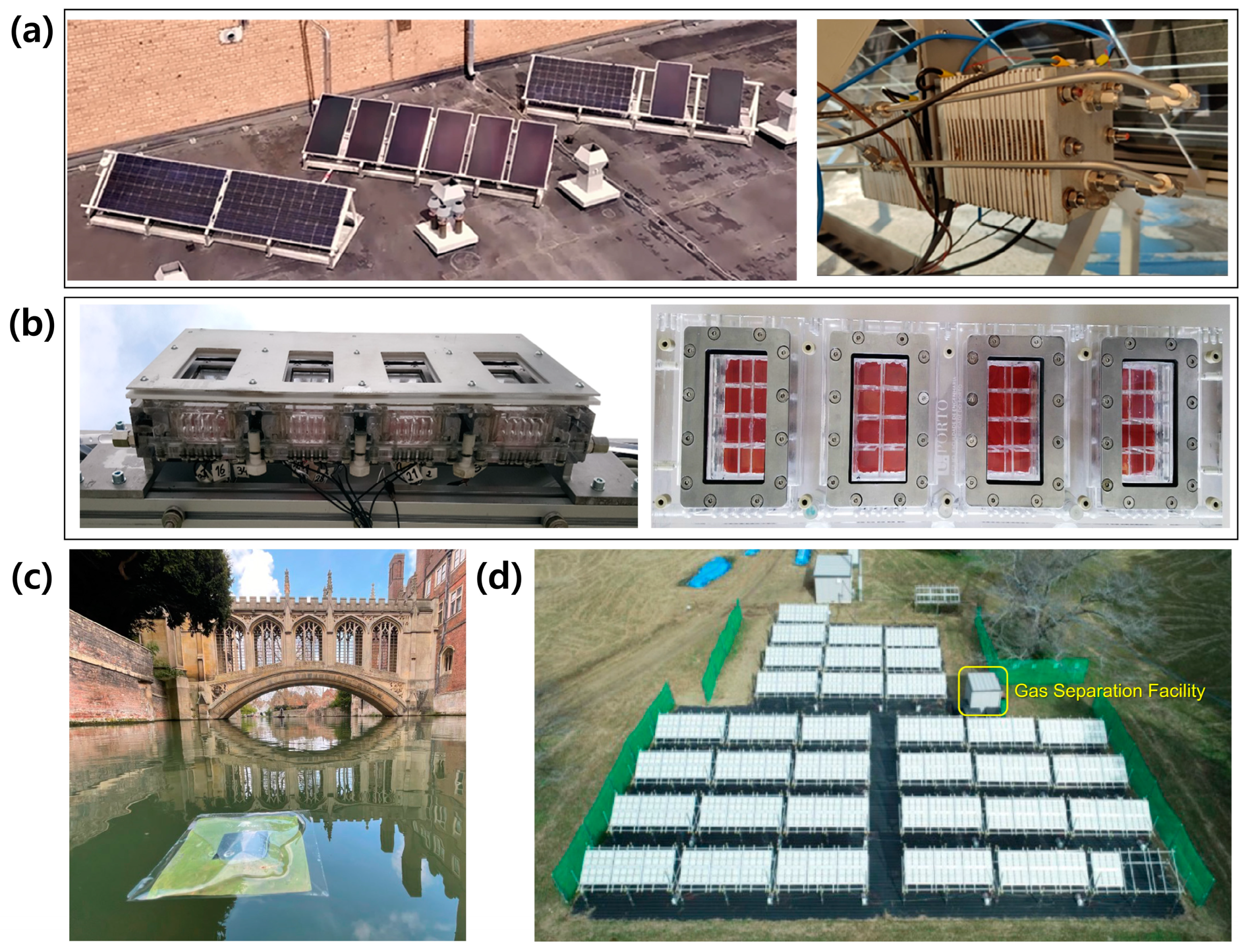

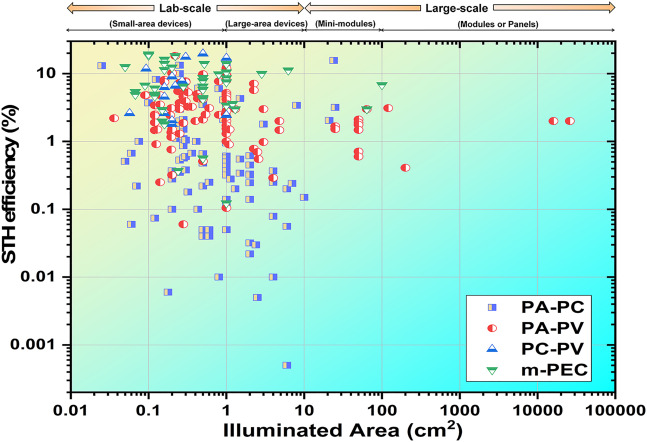

In both cases, these catalytic materials would be deposited on transparent layers in a similar fashion to solar panels, except they would produce hydrogen rather than electricity. No electrical conversion equipment or infrastructure needed! Solar hydrogen sometimes called the ‘holy grail’ of hydrogen due to its simplicity and (presumed) scalability. While it’s still considered early days, the field is growing in influence and there have even been some large-scale field demonstrations.

As elegant as this may seem, there are severe scientific, engineering and practical problems with solar-to-hydrogen and from my perspective, no straightforward means of solving them.

First, there’s the efficiency. The performance of a solar hydrogen cell is assessed in terms of the solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency: the percentage of solar energy that’s converted to hydrogen. Conventional commercially-deployed solar panels are around 20-24% efficient, and conventional electrolyzers are about 75% efficient. Electrical conversion and transmission is pretty efficient, and the losses here are usually less than 10% assuming the plant isn’t too far from the solar farm. This works out to an effective STH efficiency of 15%.

State-of-the-art lab-scale efficiencies are, at best, comparable to commercial-scale electrochemical counterparts. While lab-scale experiments have achieved STH efficiencies of 15%, larger field tests under practical conditions have resulted in sub-2% efficiencies.

But energy efficiency is just the tip of the iceberg. These materials need to be highly stable not only under HER and OER conditions but also under varying environmental conditions, such as UV light exposure, wind, rain, heat, cold, and so on. Most materials tested in the lab degrade within hours or tens of hours, with a small handful lasting over 100. But a commercial system likely needs to last for over 80,000 hours without seeing significant degradation, and possibly more than that.

And even assuming this vast chasm could be bridged, there remain fundamental engineering and implementation challenges.

First, there’s the productivity. The production rate of a solar panel is limited by sunlight—in technical terms, the plane-of-array solar irradiance. A STH efficiency of 20%—which significantly exceeds the commercial efficiencies of solar panels + electrolyzers today—results in a peak productivity of 2.5 mol/m2-hour, corresponding to a current density of 16 mA/cm2.

This optimistic, best-case production rate is over 1-2 orders of magnitude lower than commercial electrolyzers—which means all of the active cell components must also be spread over 1-2 orders of magnitude more area. While electrochemical cells and photochemical cells aren’t identical in construction, this is an enormous economic disadvantage to start off with, especially given that the catalyst assemblies are more complex than the equivalent ones in an electrochemical cell.

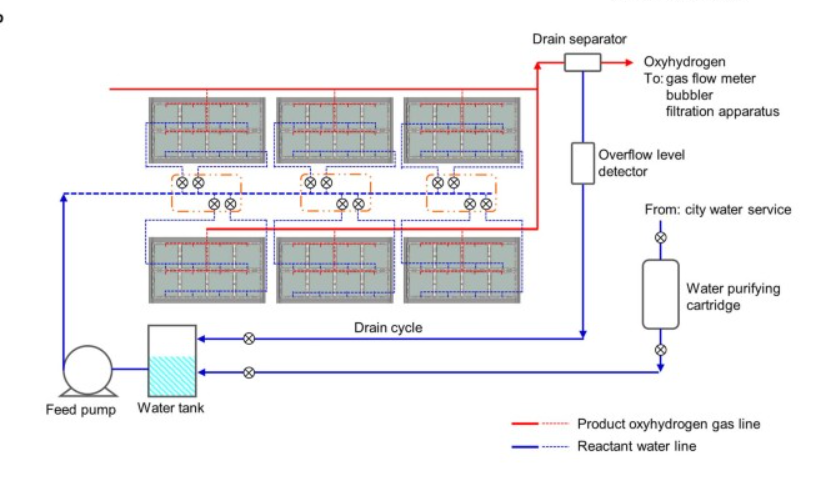

Other problems arise from the scale and scope of fluid management. Lots of small plumbing lines and pumps will need to be manifolded together to feed water to the panels and collect hydrogen (a notoriously leaky molecule). Keeping all those connections and lines leak-free will be an significant operational challenge.

For PECs there’s the additional question of electrolyte management. These systems frequently use alkaline electrolytes to improve electrode stability, which can be extremely caustic. A spill can cause major environmental damage and pose a hazard to personnel. Normally, the impact of spills is mitigated by building secondary containment structures, like retaining walls or berms. However, building secondary containment over an area the size of a solar farm would be a complete economic non-starter. Most likely, a commercial system would need to use neutral salts like phosphates, but this comes at the expense of efficiency and potentially electrode stability.

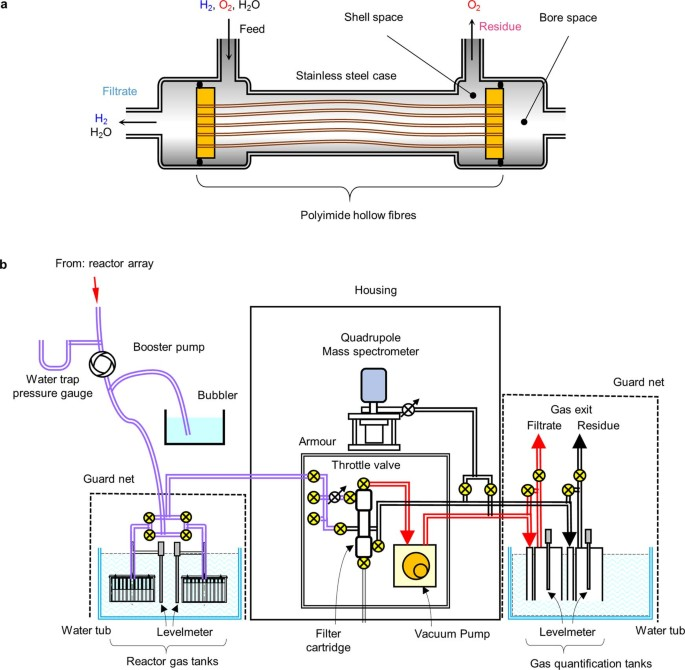

PC systems, on the other hand, have to deal with oxygen separation. In most hydrogen electrolyzers, a separator placed between the spatially separated anode and cathode to ensure that the oxygen and hydrogen don’t mix. Beyond the cell, the production facility itself is equipped with redundant safety instrumentation to detect breaches and shut down before any leaks reach dangerous levels. In PC systems the hydrogen and oxygen production isn’t spatially separated, and both of them end up in the same gas channel. This results in a flammable mixture which is rather… inconducive to maintaining a safe operating environment.

One of the most citedsolar hydrogen pilot projects solved this problem by… not addressing it. They just collected their H2 and O2 as a mixed gas and separated them in a downstream membrane system. Obviously, when the goal is simply to provide a proof-of-concept at a small scale and at ambient temperatures & pressures, this can be a pragmatic decision. But I’m skeptical this would survive a PHA in an actual commercial venture.

To be fair, solar-to-hydrogen has always been billed as a longer-term development pathway. But nevertheless, it’s hard to see how this can ever be cost-competitive with existing electrolysis technology. On every metric that matters is still orders of magnitude away from being economically competitive, even after decades of research.

Due to its technological immaturity, there haven’t been many techno-economic studies of solar hydrogen. One study estimated a production cost of \$11.4/kg under several (very generous) assumptions for efficiency, manufacturing and balance-of-system costs, and \$6.1/kg assuming the electrochemical stack components are completely free.

On the other hand, the DOE believes a production cost of \$2.10/kg (in 2007 dollars—about \$3.25/kg today) could eventually be reached assuming certain optimistic performance goals are met13. One of these goals, I should note, is an effective panel cost of \$9/m2, including installation costs14, which is cheaper than the current lowest FOB price for Chinese solar panels.

Is this a realistic assumption? Who knows! Nonetheless, the work continues. One startup, SunHydrogen, recently announced a pilot solar hydrogen project with the Australian mining giant Fortescue. I guess we’ll see.

Some takeaways

Costs are driven by requirements, not steps

The vast majority of people, including technologists, have a very poor sense of what makes something cheap or expensive to produce. This isn’t due to some individual failing—the techno-economics of large-scale production processes can be very counterintuitive. A process that’s “simpler” or requires less steps can actually be significantly more expensive when scaled up. Conversely, things that might seem wasteful may in fact be the most cost-effective means of accomplishing something. Optimizing for the system as a whole can lead to very different conclusions than narrowly optimizing for an individual step. That’s why we do detailed feasibility and techno-economic assessments in the first place!

However, there is a rough rule of thumb that applies to nearly any engineering project: cost reductions come from eliminating requirements. Does a proposed improvement actually simplify the driving constraints of a system, or does it just shift them around? Believing that removing a step in a process is what makes it cheaper is to mistake the map for the territory: the actual cost reduction comes from removing a requirement, the consequence of which is the removal of a step.

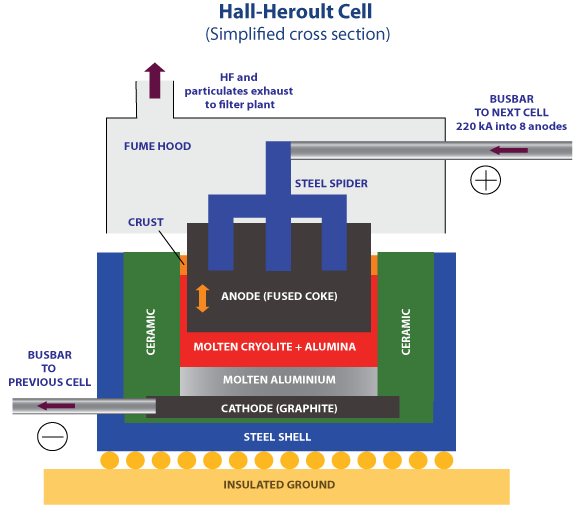

The Hall-Héroult process is a classic example. Yes, compared to its predecessor, the Deville process, it significantly reduced the number of steps required to make aluminum. But the real reason why it made aluminum so much cheaper to produce was because it eliminated the need for sodium metal as an expensive feedstock material. Most of the process simplifications subsequently came not having to manage the complexities of the sodium-aluminate reduction reaction.

This is the fundamental issue with both seawater electrolysis and solar-to-hydrogen. Their envisioned simplifications are illusory. They don’t actually result in any meaningful reduction of requirements—they simply take a bunch of requirements and shove them all into a single subsystem! This inevitably necessitates design compromises and tradeoffs that ultimately worsen performance.

Further green hydrogen research should emphasize problems outside of chemistry

It should be pretty obvious at this point that my opinion is that we’re probably not going to see major improvements on the chemistry side of things. If that isn’t going to make a big dent for hydrogen, then what will?

Getting into the specific weeds could be an essay of its own, but in a nutshell, R&D initiatives for green hydrogen should focus on the following:

- Integration requirements for various pre-existing chemical processes: hydrogen gas pressure, temperature, purity, flow rates, responsiveness, etc.

- Development of common, standardized electrolyzer process interfaces15: electrolyte temperatures, pressures, flow rates, stack voltages and currents, connector types, allowable frequency responses, and so on.

- Development of specialized power electronics for electrolytic applications: in particular, high-current, low-cost, low harmonic distortion rectifiers.

- Electricity market design, policies and financial instruments for predictable and transparent demand-response pricing for large-scale industrial customers.

Compared to cutting-edge chemistry, most of these topics are, frankly, pretty boring. Some of them are possibly more appropriate projects for professional standards bodies than academics. But that doesn’t make them unimportant: they tackle the most significant hydrogen cost drivers beyond the electrolyzer:

- Electricity prices.

- Power conversion capital costs16.

- Compression and purification capital costs.

As hydrogen electrolyzer manufacturing ramps up and the stack costs drop from economies of scale, these aspects will occupy an increasingly larger percentage of the production cost.

Evaluate impact variance and prioritize basic research

Prioritization is, by definition, zero-sum. A case for prioritizing something implies that something else should be deprioritized (read: defunded).

To be clear, I’m not some cold-hearted penny-pinching proponent of austerity, or some unimaginative bean counter opposed to scientific inquiry unless it has “practical applications”. Sustained, predictable and generous research funding is critical to all modern, advanced economies, even beyond the obvious effects of a scientific breakthrough. The vast majority of scientific research is banal and incremental—and I have no problem with this. These efforts often have—and should have—goals beyond simply publishing. They’re the primary means of providing specialized postgraduate training in the advanced skills required to make more impactful contributions down the road.

My stance here is more nuanced: we should stop funding stuff that has both expected low impact and low variance on impact. This is obviously more easily said than done: how exactly does one evaluate “variance on impact” for any random research proposal? The case of green hydrogen catalysts, though, is pretty clear-cut. We have lots of real-world data on how the economics are panning out and how they will pan out.

The supply of people who have the motivation, means and aptitude to work on complex chemistry, materials science and engineering problems is very, very finite. The last thing we should be doing is having them waste their time on pushing the state of the art in fields that frankly, don’t matter and won’t matter. In a certain sense, hungry and aspiring researchers are fungible: if someone is smart enough to work in a complex field like hydrogen catalyst development, they’re likely smart enough to work on something else that might have more unpredictability.

Beyond strong technical skills, a defining trait of great scientists and innovators is the ability to ask good questions. This is directly upstream of selecting and formulating good, impactful problems to work on (and possibly solve). To make them work on low-impact, low-upside problems is a disservice to the next generation of researchers and by extension, to humanity.

If we’re going to have people work on something that has no direct economic value, I would rather drop all pretenses and just let them work on something that seems cool, rather than have them contort themselves into pretzels trying to justify their work as ’enabling decarbonization’ or other such silliness. I’d very much rather read studies on proton-coupled electron transfer mechanisms than yet another study where they mix some random crap with graphene to make a better hydrogen catalyst.

At the margin, the boundary between applied basic research and basic applied research can be blurry, but when in doubt, we should lean more towards “interesting” and less towards “practical”. And electrochemistry has no shortage of interesting problems. They just don’t involve hydrogen.

Disclaimer: my employer, Prometheus Fuels, is working on something along these lines. ↩︎

It doesn’t increase forever. Eventually the current will asymptotically approach a maximum called the limiting current, although for water electrolysis this limit is usually so high that it is irrelevant. ↩︎

There are some additional technicalities here. In commercial systems it’s common to use the thermoneutral voltage as a basis for efficiency calculations rather than the reduction potential. This can in principle result in efficiencies of over 100%, but they are rare in practice. ↩︎

The Faradaic efficiency is completely unrelated to the energy efficiency. This is a common source of confusion and is often exploited by university communications offices who—intentionally, in my opinion—word their press releases with vague terminology like ‘an efficiency of 99%’. This is subsequently picked up by science journalists who aren’t aware of this basic fact. An energy efficiency of 99% would be fantastic, while a Faradaic efficiency of only 99% means something’s wrong. ↩︎

They’re sometimes touted as being more energy-efficient, which is possible in theory but in practice, commercial PEM electrolyzers have similar energy efficiencies as AW electrolyzers. ↩︎

The unfortunate reality is that a press release like “Scientists find cheap, efficient, stable catalyst for making oxygen” is unlikely to turn many heads. ↩︎

This is basically the exact same mechanism as metal corrosion. ↩︎

Acid-tolerant catalysts are required in proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers, which are increasingly being adopted for a variety of technical reasons. ↩︎

And since the Trump administration, have abandoned all hydrogen efforts altogether. ↩︎

For commercial applications there are strategies to increase the effective surface area beyond the geometric area, but geometric current density is still a useful benchmark. ↩︎

There are ways to break these scaling relations, but they require complex catalyst designs and it is very unlikely that you’d stumble upon them by chance. ↩︎

A recent paper suggests it might be possible to avoid using DI water. ↩︎

Historically, the DOE is rather infamous for setting completely unrealistic performance targets in their green hydrogen research programs. ↩︎

I also think the way they propose deploying the “panels” would be impractical, although I suppose at this juncture this is mostly nitpicking. ↩︎

Important note: standardization is not equivalent to modularization. The potential economic benefits of the latter are, in my opinion, much more dubious. ↩︎

Also a very common source of schedule and cost overruns. ↩︎