Why Are Green Hydrogen Projects So Expensive?

A few of my previous articles directly or indirectly discussed problems with the economics of green hydrogen. But so far, they’ve all talked about the issue in high-level terms, never getting into specifics.

I haven’t yet answered the central question: what exactly is the problem with green hydrogen electrolysis? This is the focus of this post.

Green hydrogen projects are floundering

The zero-interest rate fever dreams of the early 2020s led to widespread hype for green hydrogen. Pure-play hydrogen companies received billion-dollar valuations. Massive waves of investment poured into the sector, and multiple gigawatt-scale electrolyzer projects were announced.

The results have been dismal. Projects are being cancelled left and right, companies are fleeing the sector even with generous subsidies. The main reasons?

- Much higher costs than anticipated.

- Lack of parties willing to sign offtake agreements.

To a large extent, the latter reason was due to a combination of regulatory uncertainty, and because green hydrogen is simply too expensive.

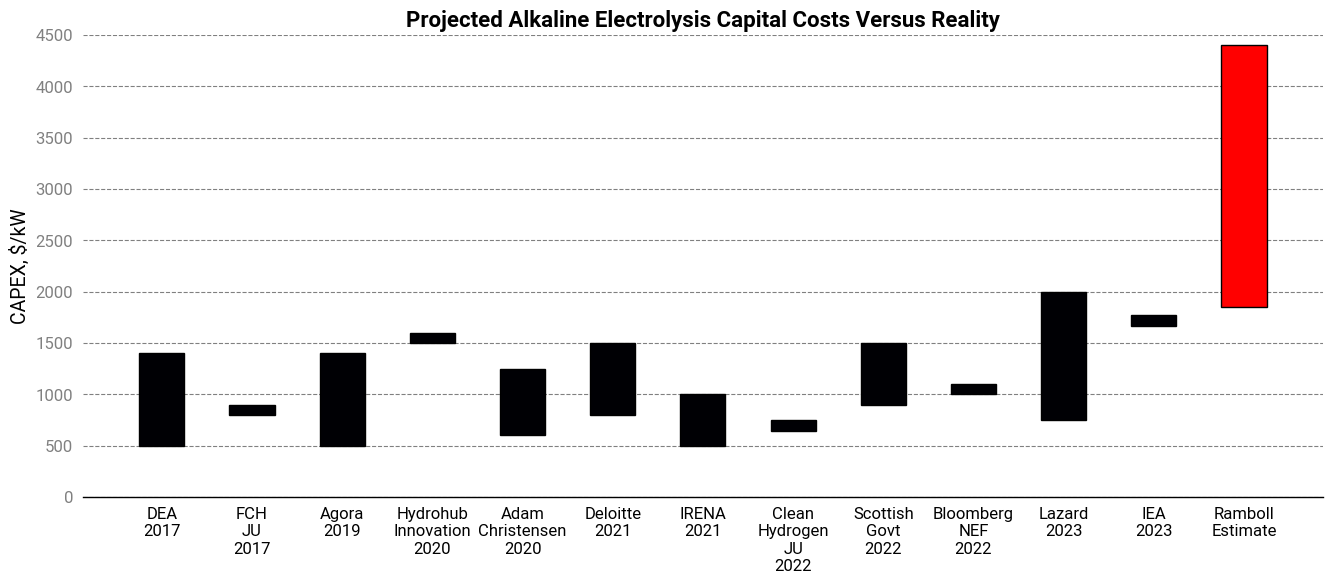

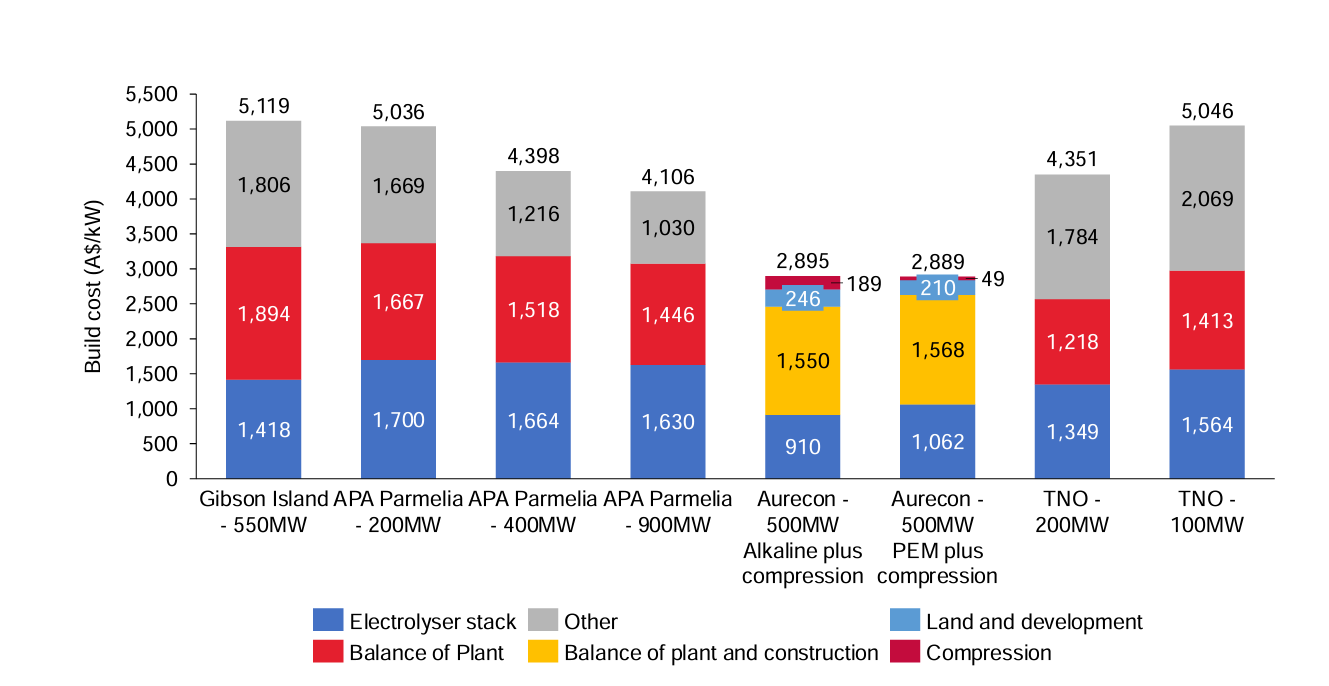

Which brings us back to the first reason. Before we had large-scale data, most analysts predicted capital costs of roughly \$1000/kW. But actual costs have turned out to be far worse: a 2023 report from the Danish engineering firm Ramboll found costs were nearly 2-5x higher!

Needless to say, this is terrible news for green hydrogen’s prospects. Why were predictions so far off the mark? Why are the costs so high? And is there anything we can do about them?

“Balance of plant” doesn’t explain these cost overruns

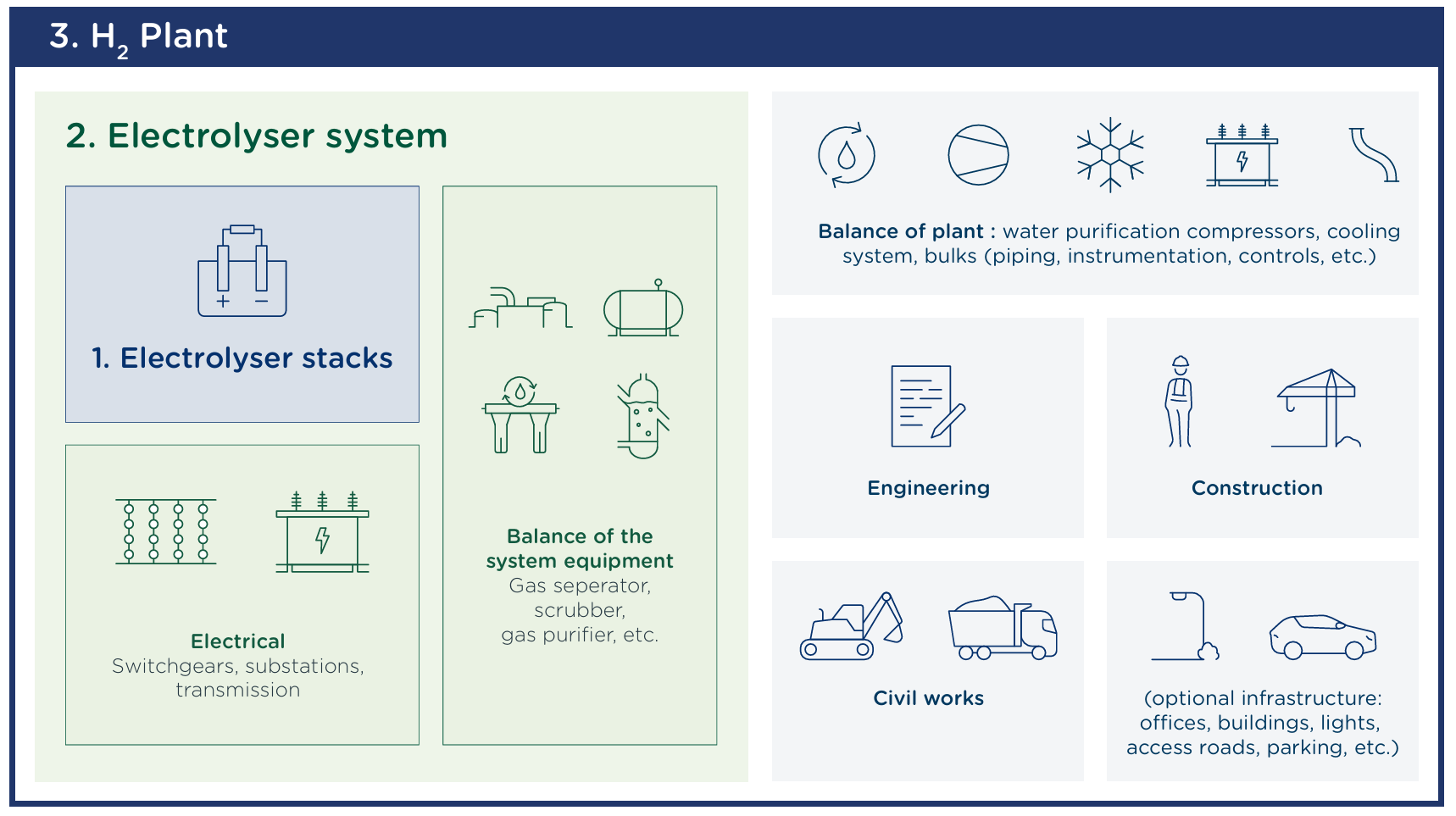

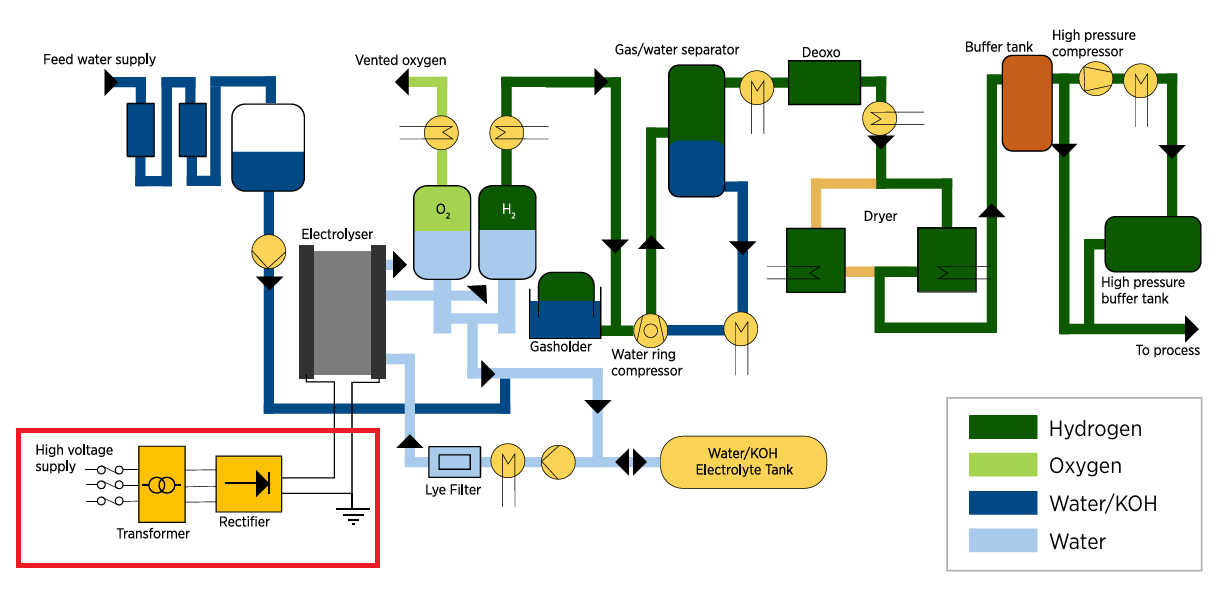

The dirty phrase in the hydrogen space these days is “balance of plant”, or BOP for short—referring to the supporting systems that provide auxiliary functions like water purification, cooling, and compression1. In practice, a lot of people use it to refer to “anything that’s not the stack”.

It’s been blamed by many analysts for the unexpected costs. The argument goes like this:

A hydrogen electrolysis plant is much more than just the electrolyzer stack. Even if the stack is amenable to mass production and significant experience curve effects, that’s not the case for the other subsystems, which are largely conventional technology, and are unlikely to decline in price.

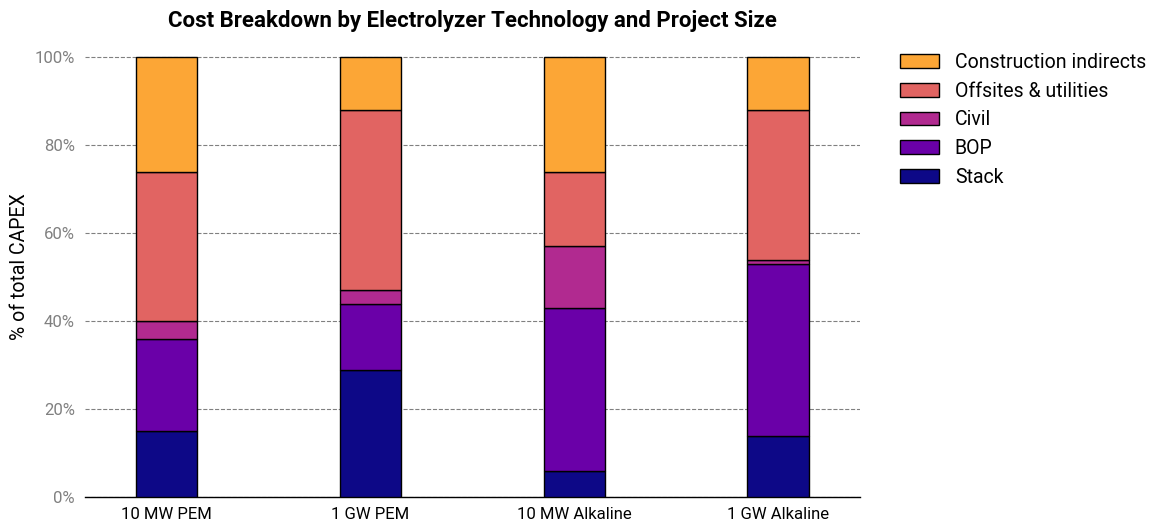

At a first glance, this seems to be supported by the data. Ramboll’s shows that the electrolyzer stack only accounts for a minor fraction of the cost of the plant—6-14% for alkaline systems and 27-29% for PEM systems.

While technically true, I think this is an overly simplistic explanation that misses a great deal of nuance. There’s something more going on here.

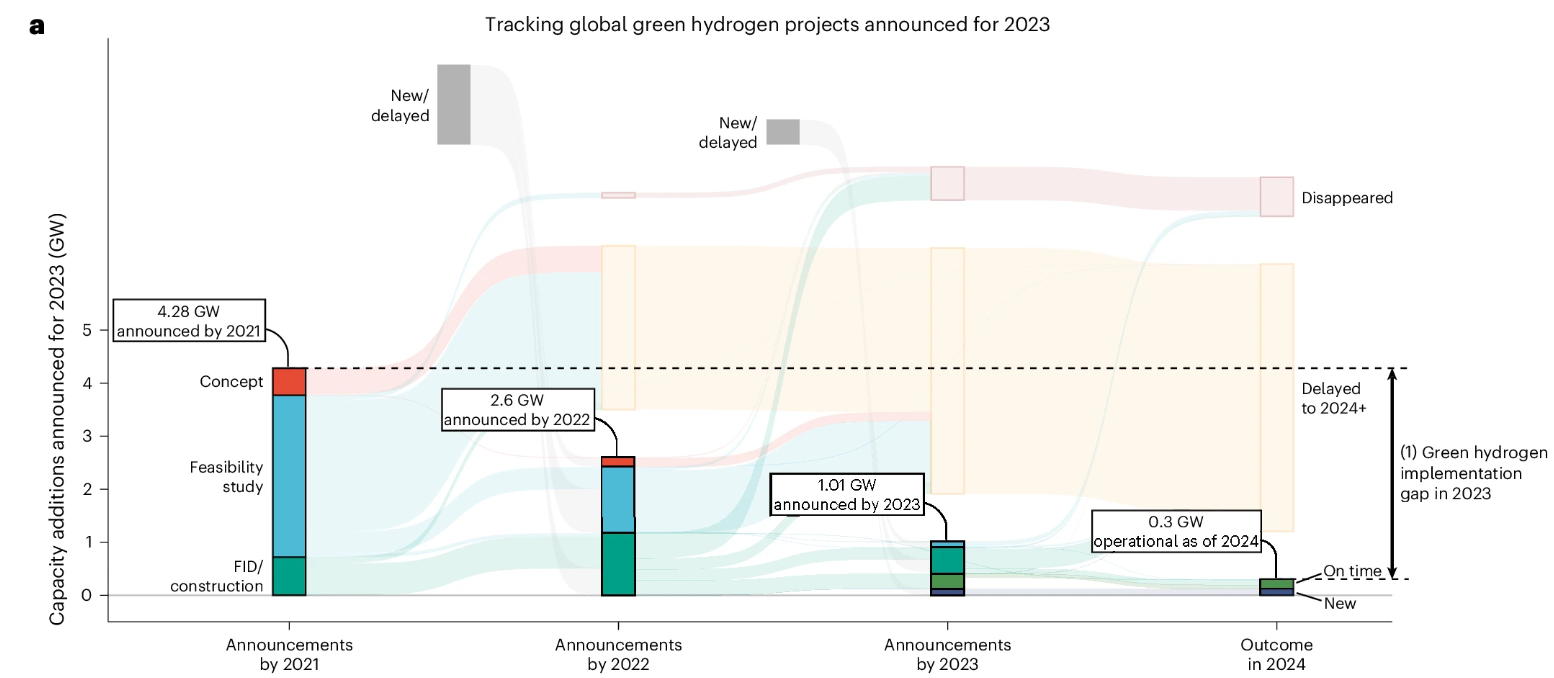

Cost escalations are happening relatively late during the project lifecycle

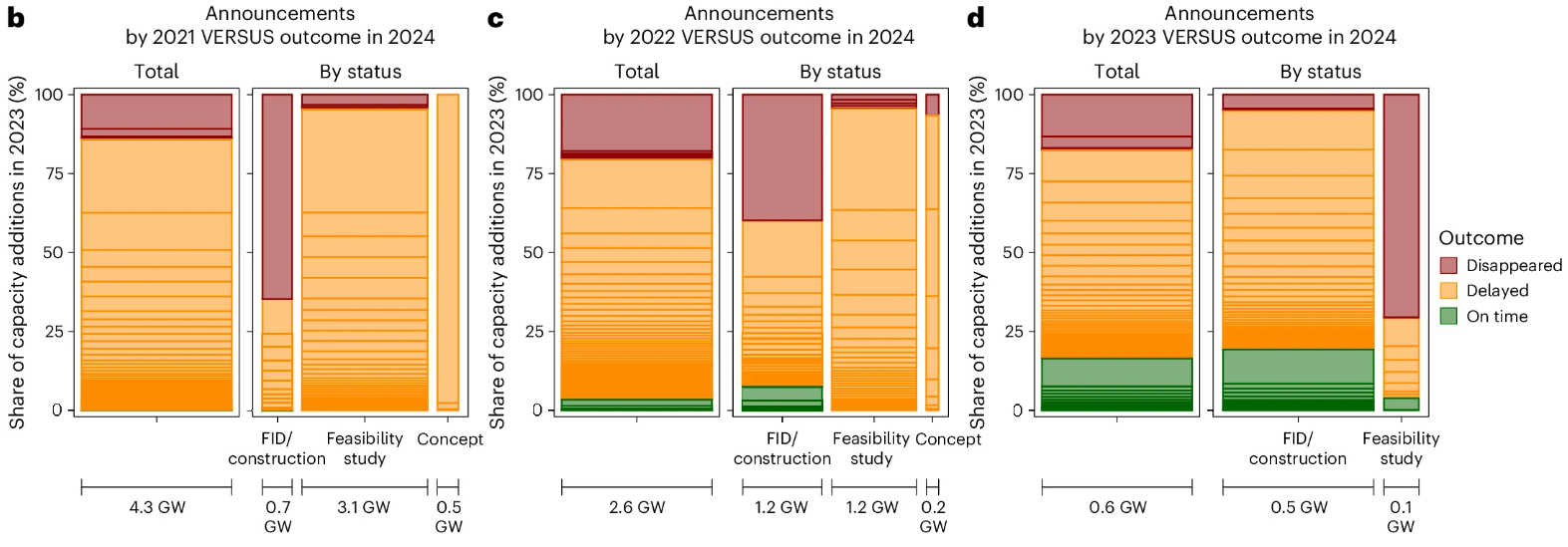

These massive cost escalations are happening during the later stages of project development. A recent analysis in Nature Energy found that virtually no green hydrogen projects in feasibility or FEED2 (Front End Engineering & Design) studies are making it past FID (Final Investment Decision).

Not every project is expected to clear the FID hurdle, but a sub-10% conversion rate is abysmal. FEED studies aren’t cheap, and companies will only embark on them if they think a venture has a good chance of panning out.

Even more concerning is the number of projects in FID running into delays or “disappearing” (read: being cancelled):

While delays are common in large, complex engineering projects, having this many is unusual. And post-FID project cancellations should almost never happen. When they do, it’s usually due to some really disastrous events like a geopolitical conflict.

This washout rate may be, in part, due to companies greenwashing and announcing studies when they have no intention of proceeding, but it also suggests that whatever’s causing difficulties with these projects must be difficult to foresee from a “bottom-up” analysis of the plant.

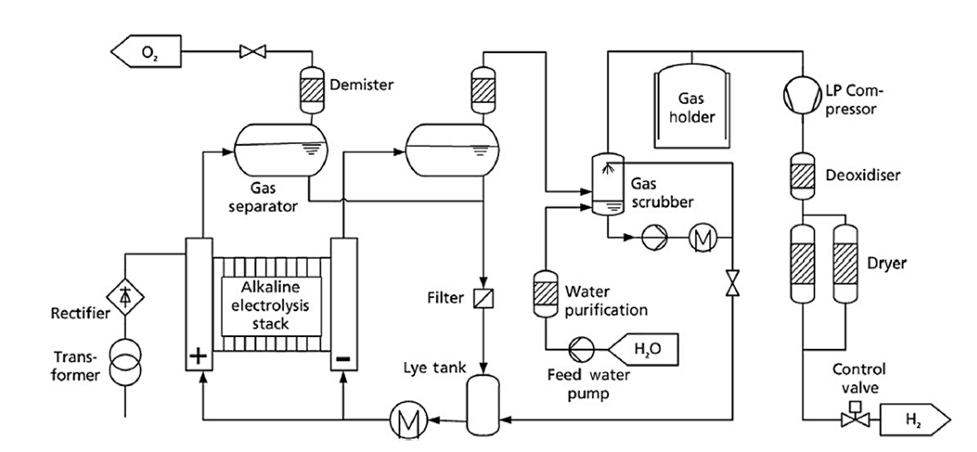

Most balance of plant subsystems are not complicated or hard to evaluate

I have trouble reconciling this with the claim the balance of plant is what’s driving costs. If that’s true, then there must be a source of hidden complexity. But looking at a process flow diagram for green hydrogen, it’s hard to see where that complexity is coming from.

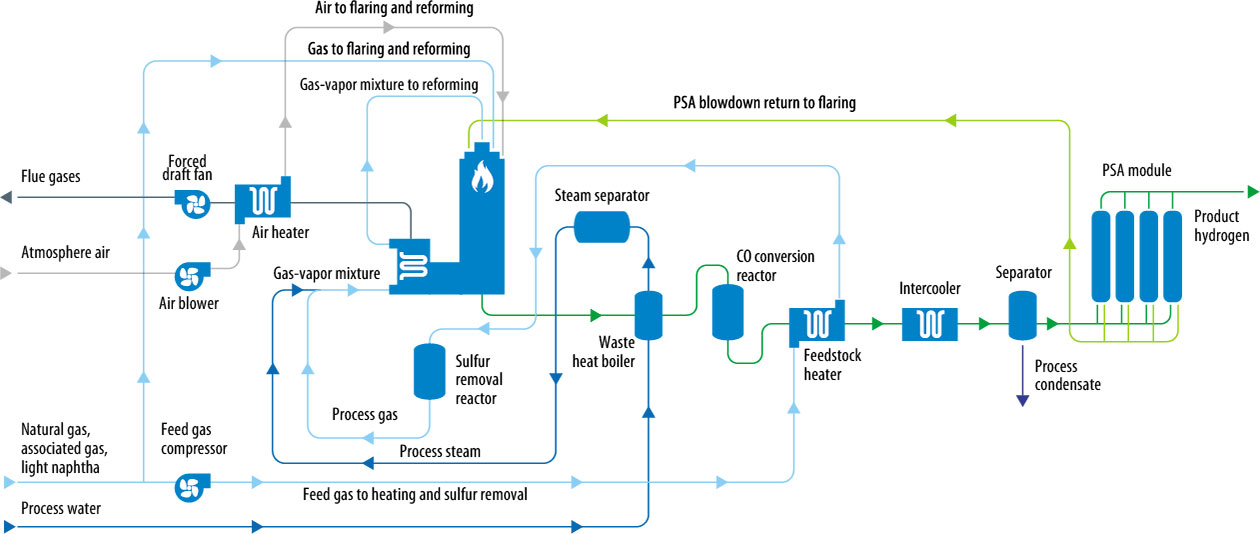

Yes, process flow diagrams are huge simplifications. But they do capture the important stuff. If you find this complicated, I’d love to know what you’d think about literally any other chemical production process. Here’s a process flow diagram for steam methane reforming:

This, incidentally, leaves out a ton of stuff, much more than the hydrogen diagram does. This paper estimates the capital cost of a steam reforming unit and including purification and compression of hydrogen, at \$397 million for a capacity of 607 tons per day. Converting those numbers to an “electrolysis basis”, that’s equivalent to a capital cost of roughly \$290/kW. Sure, they might be underestimating, as academics are wont to do, but their levelized production costs are in line with industry estimates, so they can’t be too far off.

Obviously, this isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison, but my point is that these systems aren’t inherently expensive. Operations like deoxidation, water treatment and cooling are fairly straightforward from a design perspective and use relatively inexpensive components. We’re decent at estimating how much pumps, compressors, tanks, and so on cost.

Hydrogen itself isn’t even a particularly tricky or challenging chemical to work with, from a process engineering standpoint. To be sure, using it in a widespread “hydrogen economy” context would be problematic, but in centralized industrial facilities? It’s very manageable3. Chemical engineers deal with far nastier stuff on a regular basis.

Hydrogen-compatible equipment is mostly off-the-shelf stuff constructed from standard materials, and isn’t particularly expensive as far as chemical process equipment goes4.

Now to be fair, there are indeed certain subsystems that are frequently missed or glossed over in public, conceptual-level studies5. But these would almost certainly be caught during feasibility studies or at worst, during early FEED. And they definitely wouldn’t result in projected costs double or tripling; not even close.

It’s not just random business/McKinsey-type analysts getting this wrong. You don’t reach FEED without some serious work being put in, by professionals with skin in the game. Are we implying that Wood, Worley, or Jacobs don’t know how to properly scope and cost water treatment systems? Cooling towers? Tanks? Pumps? Valves? This stuff is an EPC’s bread-and-butter. It’s utterly implausible that they would keep messing this up.

Estimation errors of this magnitude involve major design changes

A 200-450% cost overrun is enormous. Even at a feasibility stage, conventional estimation techniques (AACE Class 4) are generally within 50% of the final cost of a project.

The severity of these costing errors isn’t consistent with a mere mis-specification or even omission of process equipment. That might increase costs by 20-30%.

A 200-400% overrun is usually indicative of late-stage changes to the project scope or requirements—resulting in significant redesigns, rework, and delays.

Of course, sometimes the engineering firm messes up and under-scopes the project. Processes that are atypically complex or utilize new technologies are especially prone to this. But if that were the case, we’d expect these issues to be rectified within the first handful of projects.

The other common reason for late design changes is due to external forcing factors, such as political or regulatory actors coming in and forcing changes.

Economies of scale are not happening

BOP equipment like tanks, pumps, or compressors generally become more cost-effective the bigger they get. For instance, a pump that’s twice as big might only cost 60% more than its counterpart. This phenomenon is so common that the cost scaling of entire plants can often be crudely approximated using the same methodology.

Even if the quantity, scope, and complexity of these systems were being systematically underestimated, we would still expect these scaling rules to apply. Instead, that isn’t happening: bigger projects don’t seem to be resulting in significant cost savings as we would hope.

The problem is so pronounced that Australia’s CSIRO, in their 2024-25 GenCost report, no longer assumes any cost reductions from larger-scale projects!

There’s no reason to believe that hydrogen plant equipment is somehow the exception to cost scaling dynamics. But if these are still present, then there must somehow be diseconomies of scale cancelling out any efficiencies. That’s atypical for chemical plants—it usually happens at very large plant sizes where major challenges arise with equipment logistics and system integration.

To recap:

- Most balance-of-plant systems are fairly banal from an engineering standpoint. Attributing unanticipated costs to “balance of plant” requires many reputable organizations to have made uncharacteristically large errors in modeling and analysis.

- Given the clustering of significant cost escalations during later project stages (FEED and FID), whatever’s causing them has to be nonobvious or outside the control of experienced engineering firms.

- The magnitude of the cost overruns suggests a pattern of mid-project changes to scope and requirements.

- Balance of plant and other costs are not decreasing with larger plants, as we would normally expect to see.

These characteristics point towards elevated BOP costs as being a symptom, not a cause, of a larger and systemic issue related to project management and a failure to anticipate complexities. That leaves us with two questions:

- Where is this complexity coming from?

- Why is it not being caught earlier?

If we look at all the facts, there’s only one plausible answer.

The real problem: hydrogen electrolysis is a uniquely hard grid integration challenge

Industrial-scale hydrogen electrolysis combines:

- Very high electrical power draw

- Highly nonlinear DC loads

- Process-side failure modes requiring rapid shutdowns

Put together, these three elements make the grid-plant interface particularly troublesome. The fundamental problem stems from the need to maintain grid stability intersecting with the possibility of process-side failures.

High-power loads are a headache for grid operators

Maintaining the integrity of the grid is a two-way street: both the generation and consumption side need to be well-behaved for smooth operations. The characteristics of a load will have impacts upstream of its connection point. Two fundamental concepts in AC power transmission are harmonics and power factors.

Harmonics are caused by nonlinear loads—these are loads where the impedance changes with the applied voltage, such as switched-mode power supplies or variable frequency drives. They distort the otherwise-sinusoidal 50/60 Hz AC waveform with higher harmonic frequencies (hence the name). At high enough amplitudes, these harmonic frequencies can cause excessive current flow and degrade performance—or even damage—electric motors.

Power factor is a bit more complex. It is related to the “useful” amount of current received by the load versus the amount of current that needs to flow on the transmission system to deliver the useful current. This increases resistive losses and requires larger cables and equipment to deliver a given amount of power6.

Lower power factors are caused by harmonics, as previously mentioned, and additionally by a load’s reactance: its tendency to shift the relative phase of the alternating current and voltage due to capacitive and inductive effects.

These severity of these issues are proportional to the size of the load and utilities/grid operators will enforce limits on both to large customers.

Most importantly, however, are the load’s dynamic characteristics. To paraphrase an internet aphorism, if you’re drawing 250 kW from the grid, that’s your problem. If you’re drawing 250 MW from the grid, that’s the grid’s problem.

The issue isn’t so much the total amount of power draw as it is the potential for rapid changes in power draw. Power consumption and generation must be closely matched at all times, and fluctuations on either side need to be done at a pace that allows the other side to respond. On the load side, rapid ramp-ups are generally more problematic than rapid ramp-downs, but both are not good.

The risk profile grows nonlinearly with size. A 5 MW load suddenly disconnecting is barely noticeable. A 500 MW load suddenly and unexpectedly going offline at a single location is a catastrophe that can cause cascading trips, blackouts, and millions of dollars in damage.

As a result, many hardening measures are required to minimize the likelihood of the latter scenario. Single points of failure must be eliminated. The system will need to be capable of N-1 contingency so that equipment failures don’t bring everything crashing down. This means additional isolation, monitoring, control and redundancy capabilities than for an equivalent, small-scale facility. More analysis and testing is required to ensure these steps will meet the desired behavior.

High-power loads are a headache for plant operators

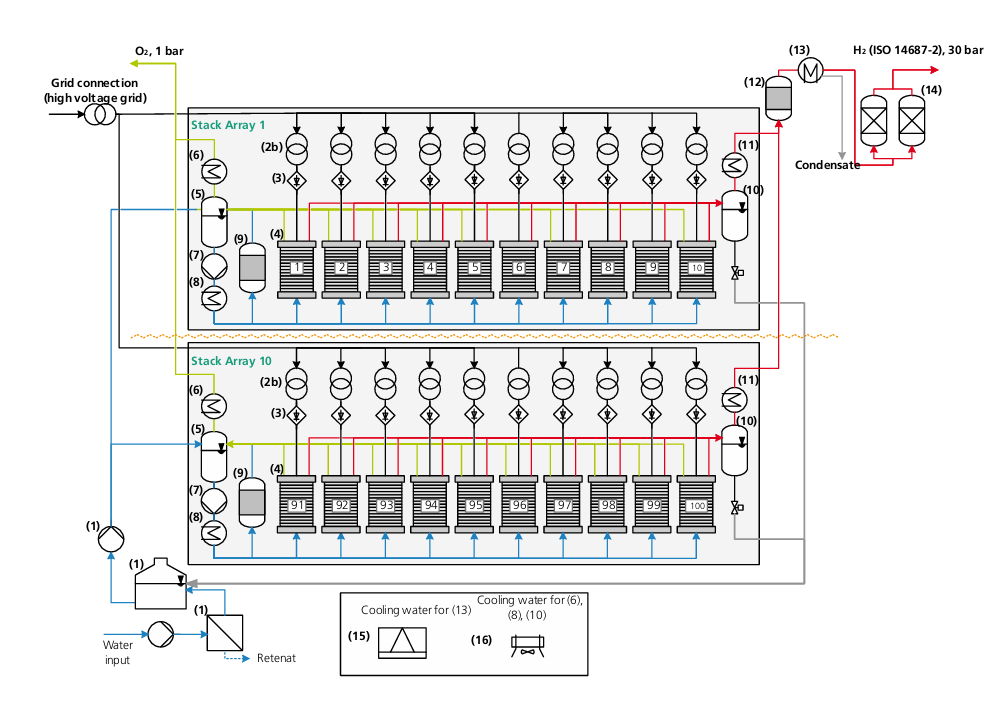

Technical publications describe the process side—including balance of plant—of electrolysis pretty well. The electrical system, however, is usually depicted as a step-down transformer (if the report is thorough, multiple step-downs) and a rectifier connected to the electrolyzer stack.

This is, sadly, very oversimplified. There’s an extensive amount of electrical infrastructure needed to reliably integrate high-power electrolyzers into the grid. There’s far too much to fully list, but hopefully this section gives a small taste.

High-power rectifiers are commonly based on a 12-pulse thyristor bridge architecture. These are notoriously nonlinear loads, with significant harmonic emissions and poor power factors. For large systems, active filtering and reactive power compensation are needed.

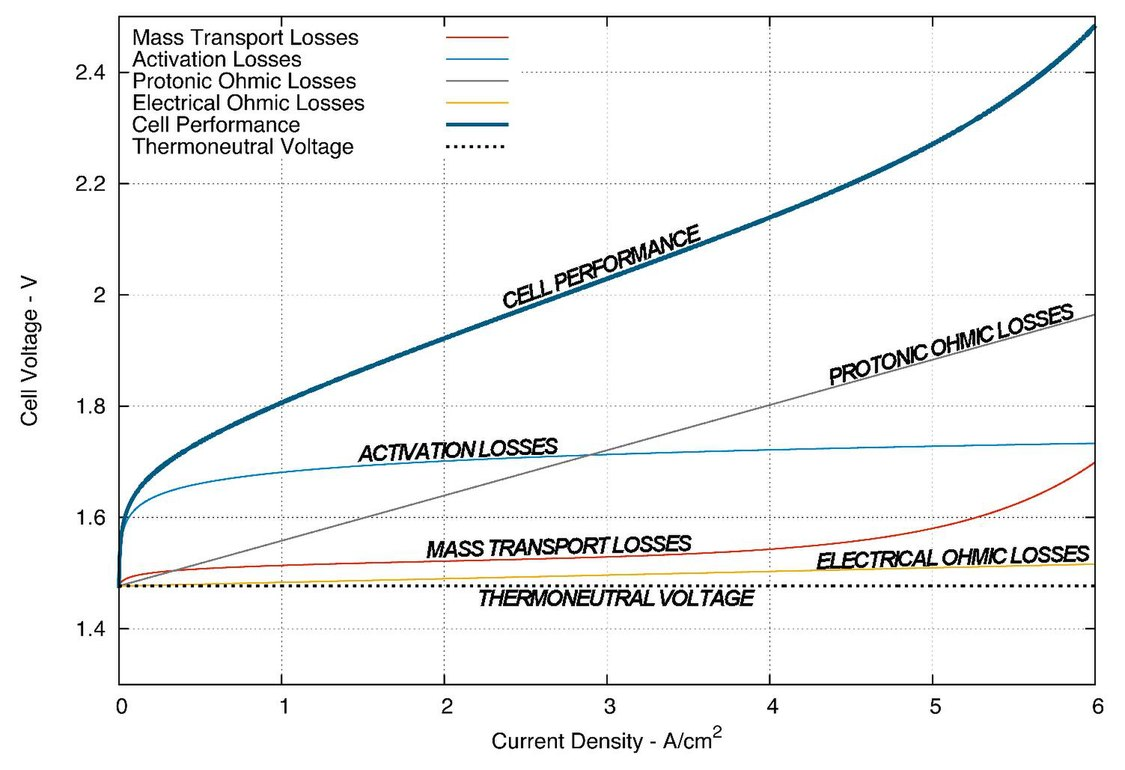

Electrolyzers themselves are also nonlinear loads. As electrical devices, they exhibit unusual behavior: when the voltage is increased, they initially admit zero or near-zero current up until a threshold, after which the current increases rapidly—even exponentially. The difference between 0% and 100% power in an electrolyzer might be less than a 20% difference in voltage.

At steady-state, this isn’t the biggest deal. The true challenge arises from transients. Real-world rectifiers with all their non-idealities are already nontrivial to analyze. Coupling these two systems together results in tricky dynamics. Power surges or collapses, and noncompliant harmonic emissions can occur if the voltage ramp isn’t well-managed.

There are additional complexities. Most alkaline electrolyzers, for instance, can’t operate at low current densities—too much hydrogen leaks over into the oxygen side, creating an explosion hazard—imposing further requirements on the electrical infrastructure.

In practice, this results in additional active filtering or voltage control on the rectifier output and carefully sequenced startup/shutdown/turnup/turndown procedures, all of which need to be carefully analyzed and validated. To meet requirements, it’s common for each stack to be equipped with its own individual transformer-rectifier.

Process-side dynamics cannot threaten grid stability

Compounding all of this are the interactions with the actual chemical process. Chemical production is inherently hazardous. There’s a lot of energy inherently present, in the form of pressure, or heat, or chemical potential.

In a large, complex system, lots of things can go wrong. Electrical faults. Electrolyzer membrane ruptures. Leaks springing on the main compression train. Cooling system failures. Equipment breakdown.

Inevitably, something will eventually happen and any industrial plant needs to be able to address it safely, by developing extensive contingency and emergency plans. But how do those plans interact with the larger system, including the grid connection?

An allowable ramp-down rate for a large customer is typically on the order of 5 MW/min7. In an emergency scenario, you’d be permitted to shed load much faster than that, but this still places constraints on the range of actions you can take—and may require you to plan for countermeasures you otherwise wouldn’t consider.

Obviously, a major rupture on a stack means you have to de-energize it. But instead of a straightforward shutdown, you may need to diverge the load elsewhere—at least temporarily. In a similar vein, a failure downstream might mean you have to stop production, but you can’t just turn off the stacks. You might need to vent the hydrogen to a flare instead. But you don’t want to vent too quickly, because rapid depressurization can damage the stack membranes!

Over the years, chemical engineers have developed many tools and frameworks for identifying process hazards and analyzing failure scenarios. When applied correctly, they’re quite effective at accomplishing their goals. Yet integrating cross-functional considerations remains challenging. The strong coupling between all these system functions leads to friction during design and project execution.

As a result, grid operators (and insurance companies) are understandably wary of large hydrogen electrolysis plants and will request extensive analysis—e.g. load flow studies, transient stability analysis, protection coordination studies—and protective equipment in place to agree to a hookup. ERCOT, for example, has a dedicated process for integrating large loads over 75 MW.

So to build a plant, you’ll need to convince them you’ve got the right stuff. Can you?

The grid operator has misaligned incentives

The grid operator and the project owner have conflicting goals.

The operator faces potentially massive amounts of liability, reputational damage and regulatory scrutiny if something goes wrong. This downside risk is asymmetric: a single major incident can overshadow years of smooth operations. Yet if the plant succeeds, then what do they get out of it? Some transmission revenue, but nothing commensurate necessarily with the amount of risk they’re potentially taking on.

The project owner, on the other hand, wants to build the plant inexpensively and begin commercial operations as quickly as possible. They will design the plant to meet all relevant safety and regulatory requirements, and no more. At the same time, the costs associated with overly conservative design specifications, such as for voltage support, ramp control, harmonic filtering, and process hardening are borne by the owner.

Unfortunately for the owner, the grid operator holds all the cards in the interconnection permitting process. The negotiations falling through represents a loss of potential revenue for the operator, but *it’s an existential threat to the project*. The owner has to come to an agreement at all costs.

Ultimately, this places the owner at the mercy of a party that is incentivized to minimize risks above all else. The operator might be sympathetic to the financial burdens incurred by design changes. There might be clauses against ‘unreasonable’ demands in the contract. But when push comes to shove, their bottom line comes first. Requirements will tend to ratchet upwards in response to new modeling results or shifts in policy. The owner has little choice to acquiesce or face project termination.

All these factors combine into the perfect breeding ground for cost blowups and lengthy delays. In this environment, we can expect:

- Enormous construction costs, exceeding projections from conceptual or early FEED studies by multiples.

- A consistent inability to predict these cost blowups using bottom-up costing approaches.

- Significant and unexpected cost escalations and supply chain delays during late FEED or after project execution has started.

- Few, if any economies of scale due to increasingly stringent interconnection requirements at higher nameplate capacities, and complex interactions between system components. A 200 MW project isn’t just a 10 MW project, 20 times bigger—it’s qualitatively different.

- An environment with many interdependencies between system components results in low productivity, manifesting as high costs for everything, rather than a single culprit that can be identified.

There is, in fact, a similar dynamic in another industry: the NRC and nuclear power plant designers. While I’m not claiming the situation is anywhere near this bad, it’s probably not an example to follow if you want reasonable project costs.

A hypothetical scenario

To illustrate what could happen in concrete terms, here’s an (entirely fictional) example that could play out in a hydrogen plant near you.

Let’s say you’re overseeing the development of a 400 MW green hydrogen facility. You’ve gone through feasibility studies and all the numbers are lining up; everything looks good. For now, you’re using provisional allowances for things like interconnection, filters, voltage support, etc, which might be on the optimistic side, but at least you’re aware of it.

You proceed to FEED studies and submit basic data to the grid operator. They analyze it and begin to conduct a system impact study (SIS). At this point, your design requirements will be driven by the characteristics of the PCC (point of common connection) such as short-circuit ratios and fault level, which you have no control over.

You’re told that you will need dynamic reactive power compensation (STATCOM/SVC) and a maximum ramp rate of $x$ MW/min. At this point, it’s already possible your initial budget didn’t account for this scale of kit.

As you proceed through the FEED, you perform detailed EMT (electromagnetic transient) studies. The harmonics get quantified against regulatory limits. Process safety analysis (e.g. HAZOP → LOPA) defines the trip scenarios and timings, which are cross-referenced in the dynamic models. A formal plant control philosophy is drafted.

At this point, you’ve made multiple design changes to comply with N-1 contingency requirements, like switching to sectionalized MV buses, adding dump resistors and BESS, and expanding the amount of instrumentation & controls.

These results are the first numbers that are precise enough for vendors to quote. Much of this kit is engineered-to-order, with quoted lead times of 18-24 months or more. To maintain schedule, you need to place an order even before FID, leaving you exposed to design changes.

You reach FID. The costs are way up, over 50% higher than the pre-FEED estimate—the FEED itself took an unusually high amount of engineering hours. The plant is expected to be just barely profitable. A bad turn of events could sink the project financially, but the board feels compelled to take a gamble and move forward because of the significant political momentum behind green hydrogen. FID is approved after much deliberation.

The interconnection agreement is signed. Mid-construction, the operator issues a supplemental study revising your ramp-rate and reactive requirements. Renewables are being installed on the grid faster than expected, leading to revised projections for IBR (inverter based resource) penetration. Additionally, a new data center project is under negotiation nearby. They tighten your ramp rate requirements to $0.6x$ and request more reactive compensation.

You call your vendors. “We can’t do that”, they claim. Procuring another unit is a nonstarter—every manufacturer has a 24 month backlog now, which would require you to pause work for over a year. Your supply chain people work the phones while your engineers try to find a workaround. But progress is slow. Everything is interlinked. Process side modifications—equipment changes, revised emergency procedures, adjusted control logic—need to be analyzed for impacts on protection coordination and transients. Every proposed change takes weeks to work through.

Eventually you find a workable solution. It’s not a good solution, but at this point you’re just aiming for “least painful” than dare to strive for more. You submit it to the operator. They get back to you 3 months later, telling you that it’s acceptable provided you also do XYZ. That requires you to rip out a bunch of already-installed equipment and conduit. Some of it, brand new, is resold for pennies on the dollar if possible; otherwise, it’s outright scrapped.

Finally, everything is installed and ready to begin commissioning. Vendor field acceptance tests reveal off-nominal harmonic behavior at certain operating points, breaching IEEE-519 compliance. No good. Either a filter redesign or control changes are needed. Either approach could take months to validate.

You opt to commission the plant at reduced capacity. This way, at least, you get something rather than nothing for the next few months.

The plant goes online. It’s 16 months behind schedule and 150% overbudget. Contractors leak stories to the trade press about late-stage rework and chaotic, confused project governance. You are unceremoniously fired for the debacle.

2 weeks later, some hydrogen electrolyzer startup in Europe is asked by investors why they won’t have a repeat of your outcome. The CTO tells them that they’re considering the balance of plant from the beginning. He points to the gas-liquid separator vessels in their artistic render, neatly perched directly above the stack. Everyone nods solemnly.

Michael Barnard writes a long-winded, gloating article dunking on the project and calling you an idiot.

A framework for understanding green hydrogen costs

Green hydrogen is an electrical engineering challenge

The grid’s structures—technical, regulatory and economic—were designed for an era of centralized generation and distributed consumption. There are only three other prominent types of industrial facilities that use very large amounts of electricity with rectified loads:

- Electrolytic smelters (e.g. aluminum).

- Chlor-alkali plants.

- Datacenters.

Relative to hydrogen electrolysis, all of these industries are much less sensitive to the capital costs of electrical equipment. Datacenters have enormous CAPEX on a kilowatt basis, and the electrical infrastructure is a minor fraction of their costs8. Smelters and chlor-alkali produce more valuable products on a per-kilowatt basis. Most of these plants, in the West, were also built long before the emergence of significant amounts of renewable generation on the grid and were designed to run uninterrupted at predictable levels for very long periods of time9.

These industries simply don’t have a good reason to push against the status quo. Consequently, we just don’t have great knowledge and “techniques” when it comes to engineering and designing these very high power draw, high variability systems at an affordable price. The solutions will tend to be overly conservative, because we don’t have a good idea of what we can ‘get away with’.

These kinds of big projects are uncommon and key knowledge propagates slowly—often through word-of-mouth at EPCs and small, specialized firms, before eventually making their way to the broader engineering public via engineering standard committees.

Nevertheless, I would expect things to improve over time, with the creation, proliferation and adoption of design standards, and as ‘best practices’ start to become better-known. It might not happen as quickly as people hope, but this also means there’s significant room for improvement and “learning effects”, as people like to say.

Integrated BOP systems are a distraction at best and a liability at worst

Unfortunately, most of the major electrolyzer OEMs show little sign that they’re aware of these issues or taking steps to address them. They’re fixated on things like alkaline versus PEM10 when every indication is that the choice doesn’t really matter, at least from a capital cost perspective. Maybe it will matter in the future,

Some companies have pivoted towards ‘modular’ solutions with completely integrated balance of plant. I believe this fundamentally misunderstands the issue. The point of modularity is to simplify the interface between components, so that the designer need not worry about the internal details. No such thing happens here. You’re still going to have intercoupling between subsystems; you’re still going to need to have control logic sequencing; you’re still going to have complicated engineering studies.

I have no reason to believe your mastery of pipe routing and sourcing and installing tanks and pumps is going to be the difference maker. None of this stuff is hard for a competent EPC! If anything, this sort of arrangement might make things worse if it unnecessarily constrains the design in ways that result in suboptimal decisions elsewhere.

Stack costs are a chicken-or-egg problem

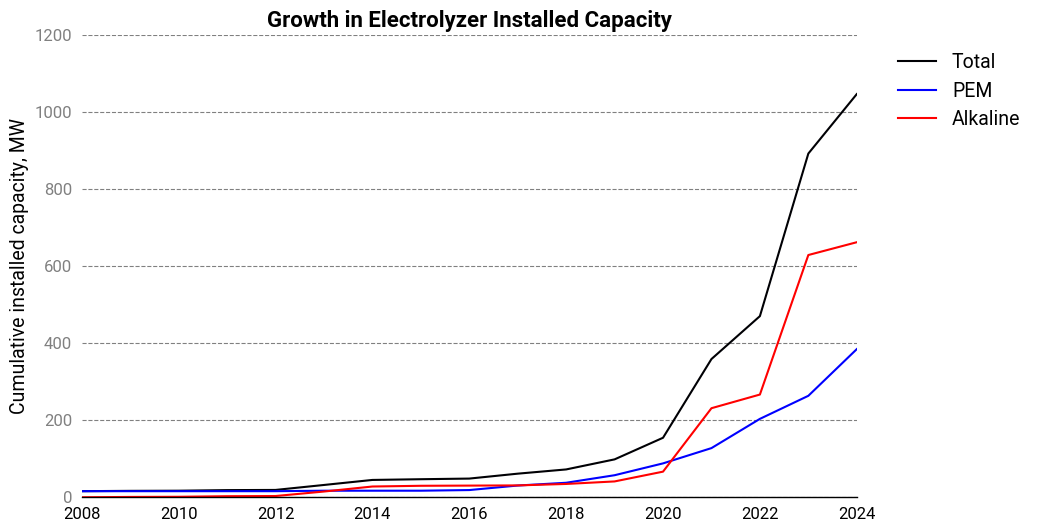

Before 2021, hydrogen electrolyzers were a small niche with every technology having less than 100 MW of installed capacity. Even in 2024, with just over 1 GW of operational projects, you could’ve probably still argued that it was a minor niche.

For alkaline electrolyzers, it’s roughly 650 MW of installed capacity. A single industrial-scale stack will have a nameplate ranging between 1-5 MW. When split across possibly dozens of manufacturers, this simply isn’t enough volume for anyone to achieve meaningful manufacturing economies.

Stack costs will come down with more volume. It’s not clear what the price floor is, but it’s clear that it’s low enough to be a non-blocker for hydrogen electrolysis. I don’t think that’s in dispute by anyone. But those volumes will need to be much larger than anything we’re currently building, and for that to happen the challenges with rest of the system have to be worked out, and the product needs to have a solid value proposition.

That last problem might be the hardest of them all.

Compression is often separated into its own distinct category as there is a lot of variance between facilities. ↩︎

For some reason, the IEA Hydrogen Production Project database includes FEED studies under “feasibility studies”, while “conceptual studies” are given a distinct category. This is, in my opinion, a bizarre way to do it. A FEED study is a completely different beast from a feasibility study. Conceptual studies, on the other hand, are a dime a dozen. A company publicly announcing its ‘conceptual studies’ is likely greenwashing. ↩︎

Embrittlement, in particular, is one of the most overrated “problems” with hydrogen. ↩︎

A notable exception are high-pressure pure hydrogen compressors, which remain quite expensive and with a limited number of vendors. But they aren’t being installed in every project. ↩︎

Two examples of frequently overlooked components for alkaline electrolyzers are first, electrolyte secondary containment structures. Second, if the electrolyzers use Raney nickel catalysts, as is commonly the case, you may need a separate, smaller electrolyte circulation loop for catalyst activation to avoid contaminating the main loop with aluminate. ↩︎

The amount of power that needs to be generated remains the same. ↩︎

In the opposite direction, a ramp-up rate limit can be much lower, around 1-2 MW/min. ↩︎

Datacenters also heavily rely on UPS systems, which can buffer the grid. ↩︎

I would also argue, with the exception of chlor-alkali plants, that process interdependencies are much less of a problem for these than they are for hydrogen. ↩︎

I have to say, if Plug is going to argue for the benefits of PEM, why would they link to a study that found alkaline electrolysis to be cheaper in every case? Couldn’t they have found something that suited their needs better? ↩︎