There is no Kantrowitz limit

Anyone who’s somewhat interested in mass transportation systems is bound to have looked into the Hyperloop concept at one point or another. One of the things that came up during my research was something called the ‘Kantrowitz limit’.

What is the Kantrowitz limit? I admittedly had never heard of it before, but it seemed like something very important that fortunately had technological solutions. Yet there was something unsatisfying about all the popular resources I could find about it. They all seemed to be very surface level, and when I started looking into it the rabbit hole ended up going a lot deeper than I expected, so I am writing this in the hopes that it might be useful to someone else one day.

Kantrowitz limit: the elevator pitch

The Kantrowitz limit is a theoretical compressible gas dynamics restriction that places a limit on the flow velocity. It was first derived in 1945 by Arthur Kantrowitz, a physicist and aerospace engineer, from whom it received its namesake, but remained relatively obscure—Modern Compressible Flow by John D. Anderson, the quintessential textbook for gas dynamics, for example, has no mention of it—until 2013, when it was reintroduced into the mainstream engineering lexicon when Elon Musk proposed his Hyperloop concept for futuristic, high-speed travel.

Musk is a little vague about the Kantrowitz limit in his Hyperloop white paper, and doesn’t really explain any of the technical details, except that it’s an important consideration when designing the Hyperlood pods. As he explains:

Whenever you have a capsule or pod (I am using the words interchangeably) moving at high speed through a tube containing air, there is a minimum tube to pod area ratio below which you will choke the flow. What this means is that if the walls of the tube and the capsule are too close together, the capsule will behave like a syringe and eventually be forced to push the entire column of air in the system.

While this is possibly useful to laymen, it is a phenomenological explanation: it describes what is happening, but doesn’t elaborate on why. Thankfully, the Wikipedia article has a fairly succinct explanation:

If a near supersonic flow experiences an area contraction, the velocity of the flow will increase until it reaches the local speed of sound, and the flow will be choked. This is the principle behind the Kantrowitz limit: it is the maximum amount of contraction a flow can experience before the flow chokes, and the flow speed can no longer be increased above this limit, independent of changes in upstream or downstream pressure.

Seems simple enough. The Kantrowitz limit is related to the gas dynamics at near-sonic flow velocities. For vehicles moving at near-supersonic speeds through a tunnel (i.e. Hyperloop pods), the Kantrowitz limit places a design constraint on the ratio of the diameter of the pod to the diameter of the tube.

What’s the hiccup?

All of this is sensible and seems well and good… except that this is a really, really basic concept that is known by anyone who has studied gas dynamics or aerodynamics at all. I’m not trying to be an elitist here: choked flow is probably taught by the second or third week of any undergraduate level gas dynamics course.

So clearly, there should be more to it than this if someone got their name attached to it! Maybe the Wikipedia explanation was incomplete? What do other online sources on it say? There’s a surprising dearth of information—most of the articles I found only give a high level explanation of the Hyperloop. Those that do dive into the relevant physics, despite otherwise widely ranging in credibility, all seem to just repeat what was said in the Hyperloop whitepaper.

Here are a few examples:

- This article by Mapping Ignorance repeats the “syringe effect”, and also cites an equation that seems to have been taken from the Wikipedia article1.

- CNBC’s article doesn’t really mention the concept and just explains that compressor fan will “transfer high air pressure from [the pod’s] front to the rear and sides”.

- Brilliant.org has a section on the Physics of Hyperloop where they also repeat the same claims about the Kantrowitz limit and the syringe effect. They directly quote the white paper on this.

- An article by Jalopnik specifically about the Kantrowitz limit just uncritically rephrases what Musk wrote, but it does cite a paper on the topic! But this paper assumes that you already know what the limit is, so some more digging is required.

- I also found this from a site called HyperloopDesign.net which claims that there is no Kantrowitz limit for Hyperloop pods. However, their explanation of the relevant physics seems very dubious2, so I’m not going to consider their argument further.

So what is the Kantrowitz limit, really?

Without a satisfactory explanation, I decided to read the original 1945 paper3 by Kantrowitz and Donaldson. They were studying the design of diffusers for supersonic air streams (i.e. air intakes for supersonic planes). In short, the Kantrowitz limit has to do with the stability of normal shocks in variable-area ducts when decelerating gases from supersonic to subsonic velocities.

Choked flow: an explanation

Let’s do a brief aside and discuss the concept of choked flow, since it is rather critical to understanding the issue at hand. You can skip this section if you are already familiar with the relevant physics.

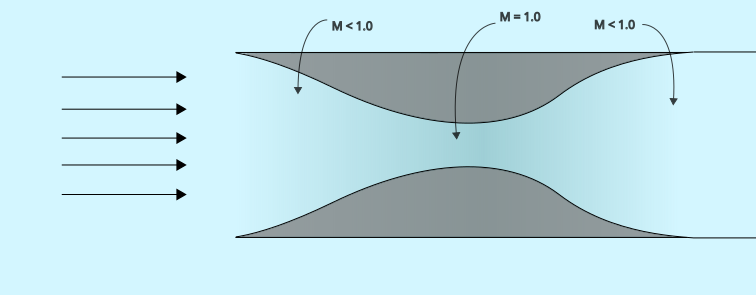

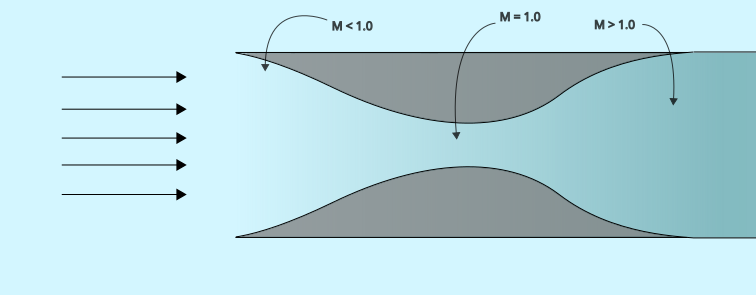

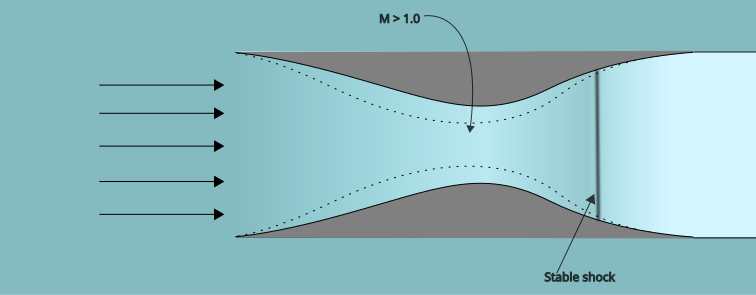

Consider a gas flowing through a variable-area duct4. As the area of the duct shrinks, the gas must either speed up or compress (become denser) to maintain the same mass flow rate. The maximum speed that the gas can reach through a reduction in area is the speed of sound. Once this speed is reached, any further reduction in area cannot increase the speed further (and in fact the gas will always reach Mach 1 at the vena contracta, or point with the smallest cross-sectional area, as long as this area is below the critical area).

At this point, any further reduction of the pressure downstream of the duct will not influence the flow rate; it is considered choked. However, increasing the pressure upstream will increase the mass flow rate by increasing the density of the gas, but the volumetric flow rate will remain roughly the same. So there is a “critical” amount of shrinkage the duct area can undergo before the flow reaches Mach 1. This, of course, depends on how much the gas decides to speed up vs. compress when the area is reduced, and the “speed-up-to-densification” ratio depends on the assumptions you make of the gas.

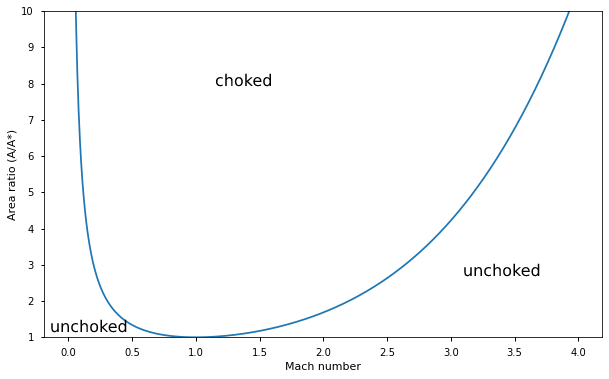

Most commonly, we assume that the gas is calorically perfect5, and that the compression process is isentropic. In this case, the relationship between the choking contraction ratio and the airspeed is known as the area-Mach number relation:

$$ \frac{1}{\text{Contraction ratio}} = \frac{A^*}{A} = M\left[\frac{2}{\gamma+1}\left(1 + \frac{\gamma-1}{2}M^2\right)\right]^{-\frac{\gamma+1}{2(\gamma-1)}} $$

Where $M$ is the Mach number at some point in the duct (usually the entrance), $A$ is the area at the point in the duct where $M$ was taken, $A^*$ is the cross-sectional area at the minimum area of the duct (known as the throat), and $\gamma$ is the heat capacity ratio, which varies depending on the gas but for air is roughly equal to 1.4. The interesting thing about this equation is how the contraction ratio only depends on the Mach number; there are no variables for temperature, pressure, density, etc.

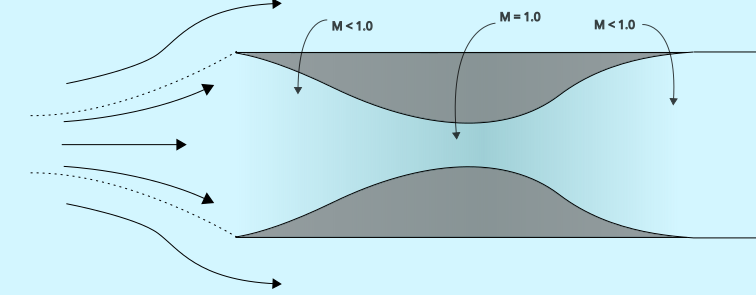

Something worth noting is that there are actually two solutions of $M$ for a given contraction ratio: one for $M<1.0$ and one for $M>1.0$. This means for any given ratio, there is a subsonic speed below which the flow will not choke and a supersonic speed above which the flow will not choke, surprisingly enough.

The problem with supersonic deceleration

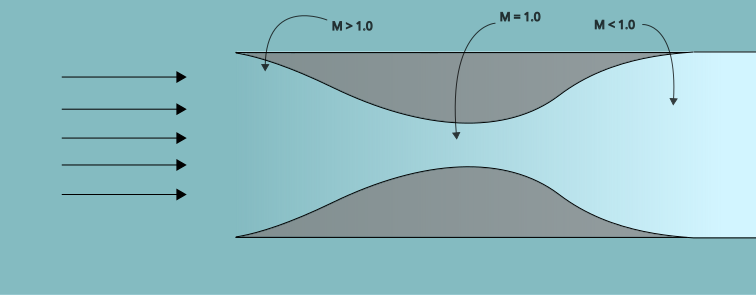

Since this process is isentropic and therefore reversible, one would imagine that the opposite scenario should also be possible: a converging-diverging inlet that decelerates supersonic gas to subsonic velocities.

In practice, however, this kind of arrangement is not possible to achieve and maintain. There are two problems.

The first is that generally, before reaching a supersonic velocity, the system has to first accelerate through a subsonic regime. And a subsonic flow will also choke the inlet, but at a much lower mass flow rate. As the system speeds up in the subsonic regime, some of the gas must get diverted away from the inlet as it cannot “fit” through the throat. The ratio of air diverted away to air entering the inlet is called the capture ratio.

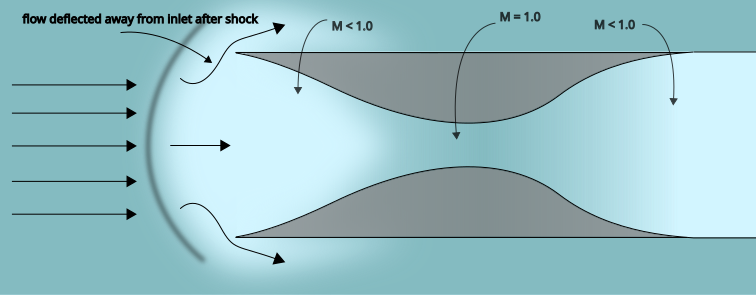

As the airspeed increases further and turns supersonic, the gas can no longer turn away in time (since it cannot receive information faster than the speed of sound). A bow shock will form in front of the inlet, and the subsonic gas on the other side can turn away from the inlet, maintaining mass continuity.

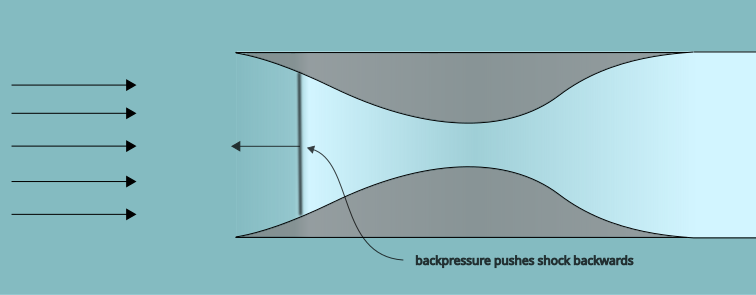

The second problem is that even if a smooth supersonic deceleration is achieved, it is inherently unstable. Since the outgoing flow is subsonic, information about disturbances downstream (such as pressure fluctuations) would be able to propagate through it, lowering the mass flow rate, if only temporarily. However, since the entering gas is supersonic, information cannot propagate upstream through it, and its mass flow rate will remain unchanged. As Kantrowitz explains, “it therefore appears that isentropic deceleration through the speed of sound in channels is unstable and unattainable in practice.”

Implications of shock waves

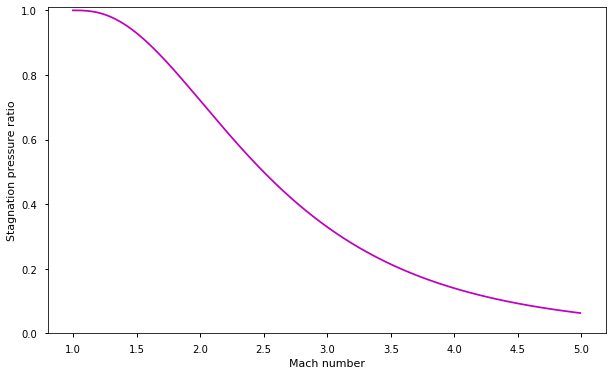

Shocks are highly irreversible phenomena and will lead to significant amounts of energy dissipation. The total losses across the shock wave are captured by the drop in stagnation pressure. The stagnation pressure drop across a shock wave is given by the following equation: $$ \frac{p_{t2}}{p_{t1}} = \left(\frac{\frac{\gamma+1}{2}M_1^2}{1 + \frac{\gamma-1}{2}M_1^2}\right)^{\frac{\gamma}{\gamma-1}} \left(\frac{1}{\frac{2\gamma}{\gamma+1}M_1^2 - \frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma+1}}\right)^{\frac{1}{\gamma-1}} $$ Where $p_t$ is the total, or stagnation pressure, and the subscripts 1 and 2 denote before and after the shock, respectively. The stagnation pressure, is, in turn, directly proportional to the mass flow rate through the duct, as given by the following equation: $$ \dot m = \frac{p_t A}{\sqrt{T_t}}\sqrt{\frac{\gamma}{R}}\left(\frac{\gamma+1}{2}\right)^{-\frac{\gamma+1}{2(\gamma-1)}} $$ For a given duct area $A$, the mass flow rate depends on the total pressure and the total temperature. Because a shock is adiabatic, the stagnation temperature does not change across a shock, so $\dot m \propto p_t$ only.

Thus, a shock wave will result in total pressure losses. These losses will reduce the mass flow rate through the inlet by the proportional drop in the pressure. A smaller mass flow rate means a smaller throat area is needed to choke the flow.

So the Kantrowitz limit basically is just the area-Mach number relation multiplied by the stagnation pressure ratio across a normal shock.

Effect of the Kantrowitz “limit”

Writing out the equation, the Kantrowitz limit is the area ratio denoted by: $$ \overbrace{\frac{A_4}{A_0}}^{\text{area ratio}} = \overbrace{M\left[\frac{2}{\gamma+1}\left(1 + \frac{\gamma-1}{2}M^2\right)\right]^{-\frac{\gamma+1}{2(\gamma-1)}} }^{\text{area-Mach number relation}} \underbrace{ \left(\frac{\frac{\gamma+1}{2}M^2}{1 + \frac{\gamma-1}{2}M^2}\right)^{\frac{\gamma}{\gamma-1}} \left(\frac{1}{\frac{2\gamma}{\gamma+1}M^2 - \frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma+1}}\right)^{\frac{1}{\gamma-1}} }_{\text{stagnation pressure ratio across normal shock}} $$ Simplifying and rearranging gives us the same form as the Wikipedia article: $$ \frac{A_4}{A_0} = M_0 \left(\frac{\gamma+1}{2+(\gamma -1)M_0^2}\right)^{-\frac{\gamma+1}{2(\gamma-1)}} \left[\frac{(\gamma+1)M_0^2}{(\gamma-1)M^2_0+2}\right]^\frac{-\gamma}{\gamma-1} \left[\frac{\gamma+1}{2\gamma M^2_0-(\gamma-1)}\right]^\frac{-1}{\gamma-1} $$

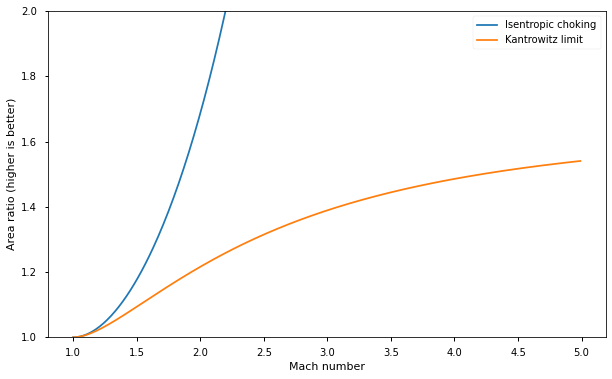

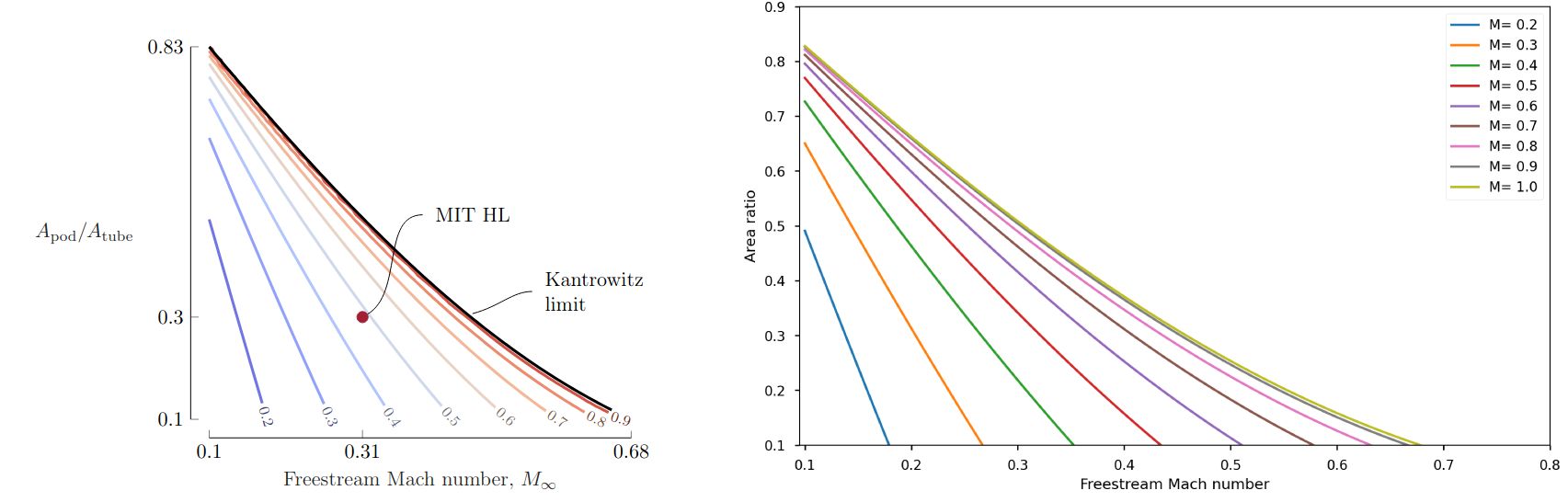

Plotting it out compared the basic isentropic compression case, it’s clear that the shock will greatly limit the design contraction ratio.

The Kantrowitz limit is thus relevant when a supersonic flow needs to be decelerated to subsonic flow, such as is the case in air intake ducts on supersonic planes. It appears repeatedly in the literature mostly in papers dealing with the design of supersonic intake ducts.

And perhaps instead of “limit”, a more appropriate term would be “effect”, as it’s not really a limit at all. It’s an aerodynamics phenomenon that results in suboptimal mass flow/pressure recovery, but it’s not an outright cap on the performance of a system, like the term “limit” would imply.

To my great surprise, it does seem like everyone has gotten this wrong—no one I found correctly explained this, and usually just parroted the “syringe” explanation from the Musk paper, despite the original paper by Kantrowitz being readily available online (and rather short: the meat and bones of it is only about 5 pages).

Overcoming the limit

The Kantrowitz “effect” is undesirable as the pressure losses across the shock lower the mass flow rate through the duct. The total pressure ratio is also known as the pressure recovery, with a perfect pressure recovery being a value of 1.

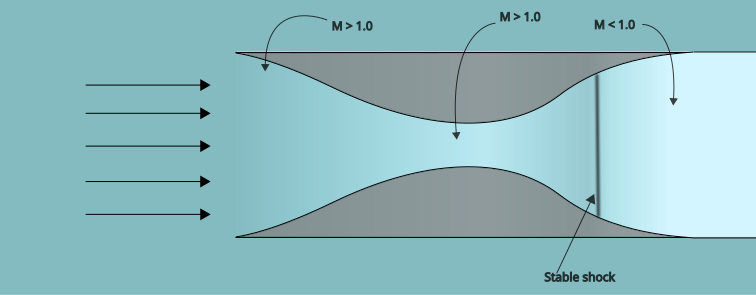

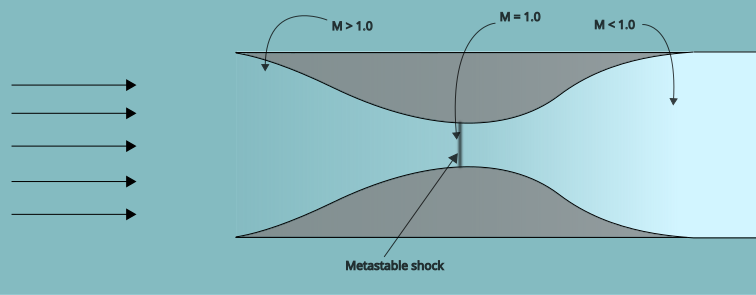

But as it isn’t a hard limit, there are a few workarounds that can be employed to mitigate its effect. The general goal is to make the shock weaker, which will improve the pressure recovery. The most common way to do this is to move the shock wave into the inlet, behind the throat. In this position, it is stable, and is much weaker than if it were outside and in front of the inlet. This is often referred to as “starting” the inlet.

Overspeeding

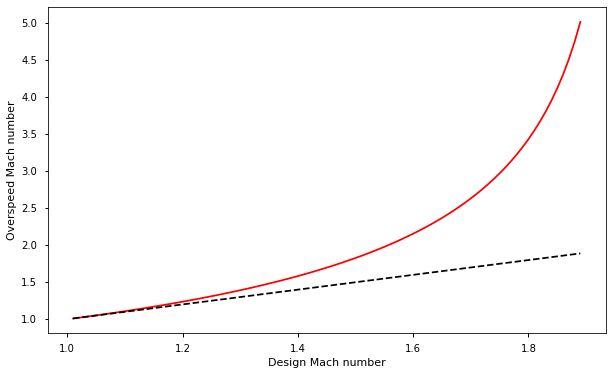

The simplest solution is to temporarily overspeed the system above the design Mach number.

As the shock moves through the converging duct, a positive feedback loop will occur: its upstream Mach number will decrease, which means that the shock will weaken. This results in the throat experiencing an increased mass flow rate, which will reduce the shock backpressure which draws the shock further into the duct. Thus the shock will continue moving until it has passed through the throat.

However, the opposite situation is also true. As previously mentioned, if the shock is placed at exactly the throat, and there is a temporary backpressure fluctuation, then that could be enough to knock the shock wave out of the inlet, leading to massive energy losses.

This is only a viable option for systems operating at relatively low Mach numbers. Beyond a design value of ~Mach 1.6 the amount of overspeeding needed becomes impractical from an engineering standpoint, and above Mach 1.9 it becomes flat out impossible.

Increasing the throat size

Kantrowitz and Donaldson propose a simple solution: increasing the throat size so that it chokes at a subsonic mass flow rate equal to the expected mass flow rate during supersonic operation at the design Mach number. This inlet design is also known as a Kantrowitz-Donaldson inlet, and it is self-starting, because it will naturally settle at the desirable equilibrium point.

The downside is that the pressure recovery is lower than that of a normally-sized inlet since the inlet isn’t designed for the desired mass flow rate. The larger throat means the gas will decelerate less before reaching the shock, resulting in more pressure losses. So the tradeoff is whether you want a self-starting inlet that works at ~85% performance or one that needs to be manually started but works at ~95% performance.

Using variable nozzles

In a similar vein, another solution is to adjust the size of the throat in real time to move the shock past the throat before closing it back up. This approach results in high pressure recovery (and therefore high performance), at the cost of complexity and additional weight.

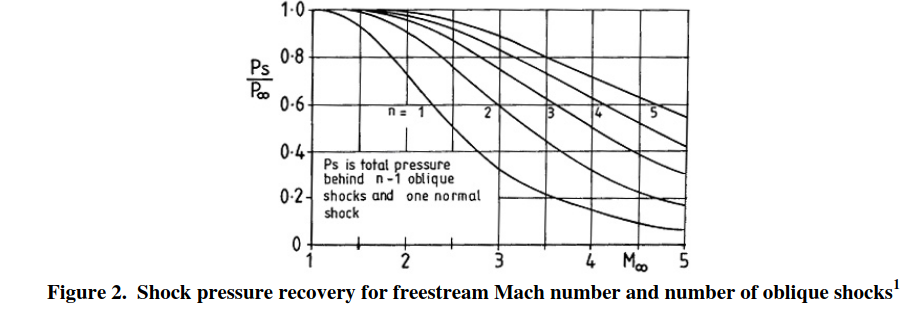

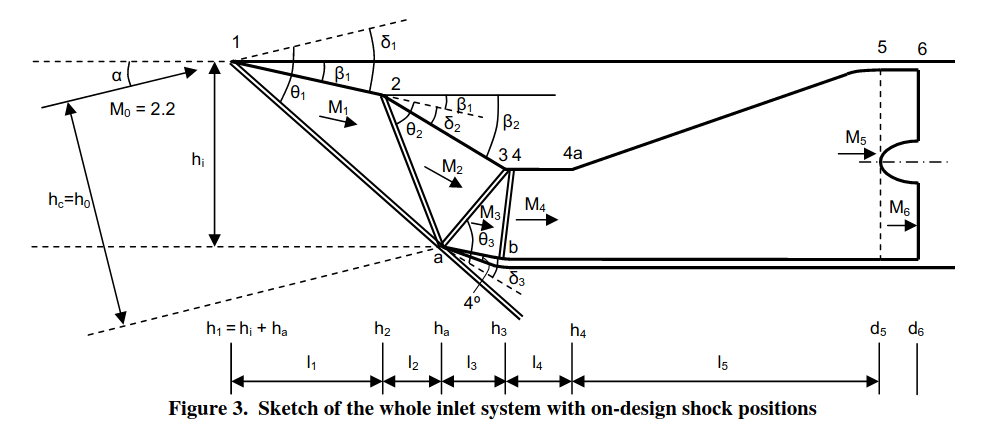

Oblique shocks

The last solution is to use a geometry that will force the airflow to turn, producing a series of oblique shocks instead. These will lead to lower pressure losses than a single normal shock. These changes in angle are called ramps. This can be done through systems like intake ramps or inlet cones, which are a common sight on supersonic aircraft. Inlets that have these shocks occur outside of the inlet are called external compression inlets, while those with shocks that occur inside the intake are called internal compression inlets.

The design of these intakes is a complex topic with a lot of literature behind it, and beyond the scope of this post.

What about Hyperloop?

A lot of these considerations pertain to the design of aircraft, but let’s return to the original subject matter. The Kantrowitz limit doesn’t seem to be relevant to Hyperloop systems at all. It necessarily only applies to supersonic systems. The vast majority of concepts I’ve seen still have pods traveling at subsonic velocities, which means you wouldn’t have the formation of a shock wave in front of the vehicle.

This doesn’t mean that the flow won’t choke, but the massive loss in stagnation pressure due to the shock is the reason why the choked mass flow rate will be significantly lower than what would otherwise be possible.

What will actually happen?

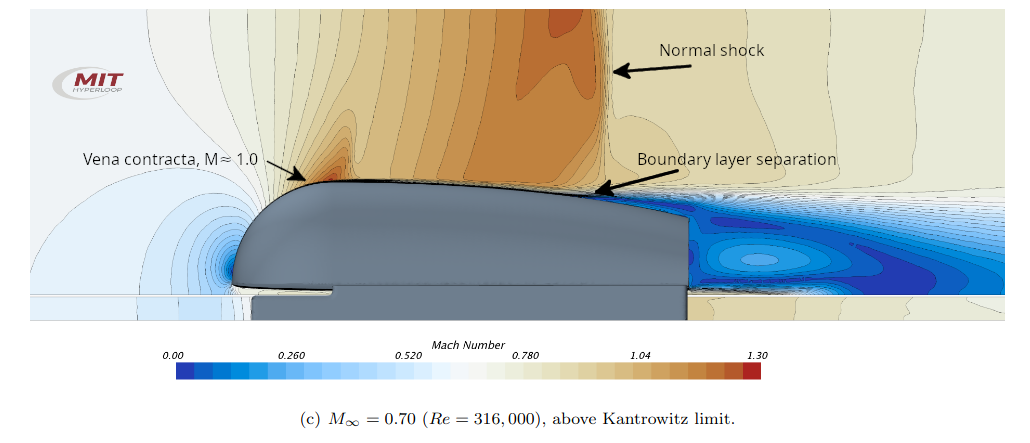

So far, I’ve described the Kantrowitz effect in a scenario with free-flowing air, such as on aircraft: if the air cannot enter the duct, it simply flows around it. With Hyperloop, the situation is a bit different, since it’s in a closed tunnel, and there’s nowhere for the air to go except behind the the pod.

Based on the classical theory of gas dynamics, I would expect the following to happen as the Hyperloop capsule zips down the tube and reaches the choking velocity for its contraction ratio:

- The flow reaches Mach 1 at the narrowest point between the capsule and the tunnel.

- Static pressure would build up in front of the capsule until the pressure is sufficient for the mass flow rates to equalize.

- Depending on the pod geometry, the flow may briefly accelerate past Mach 1 before hitting a shock wave as it encounters the backpressure from the air behind the capsule.

- The drag will increase due to the increased pressure in front as well as the wave drag from the shock wave.

Is a compressor worth it?

So Hyperloop pods will likely experience an increase in drag as they approach the sonic condition in the bypass duct. But the key question is: how much extra drag?

This is where Musk’s analogy of a syringe effect is, in my opinion, very misleading. The reason why the resistance of squeezing a plugged syringe rises so rapidly is because you are compressing the air to several multiples of its original pressure (presumably atmospheric). But in a tube that’s presumably hundreds or thousands of miles long, this effect would be a lot less dramatic. Yes, the pressure in front of the pod increases, but this would have the effect of increasing the mass flow through the bypass (recall the mass flow equation), so the system would eventually reach a steady-state equilibrium, so the force wouldn’t increase in an unbounded manner. But where does this steady state lie?

The answer to this question is very complex and requires the use of simulations to get meaningful answers. My gut feeling, based on drag profiles of transonic aircraft6, is that the increase in drag would significant, but it would be on the order of 3-4x more as opposed a complete showstopper like 100x7. Since the drag of a a Hyperloop pod in near-vacuum conditions is already very low, it’s questionable whether adding a compressor or other onboard system to mitigate the effect is worth it at all.

Obviously, this depends on how big the pod is relative to the tunnel. But I suspect that other practical considerations, such as engineering tolerances and supporting equipment, will place an upper limit on the pod size before the drag from densified air in front becomes the main consideration.

Examples from a study

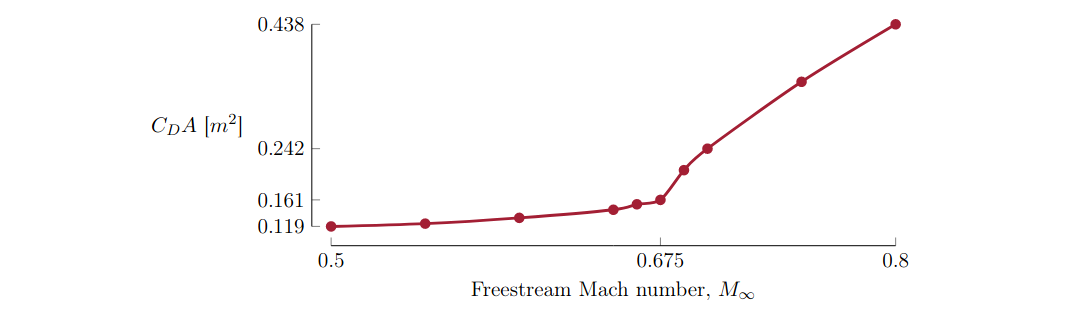

One good example would be this 2018 paper by Opgenoord and Caplan on Hyperloop pod aerodynamics, where they did some CFD studies on a pod design. It showcases some of the effects I previously mentioned.

Their conclusion is that the drag coefficient does begin to increase significantly after choked flow is reached, but by a factor of ~3 for the speed range that they studied. They also concluded that adding a compressor would consume more energy than beefing up the propulsion system to deal with the increased drag. The difference is 231 kW to power the compressor vs. 31 kW to overcome drag—nearly an order of magnitude difference!

Despite this, a lot of the concept art for Hyperloops depicts pods with gigantic compressors in the front.

What about supersonic Hyperloop pods?

It’s true that supersonic pods have explicitly not been left off the table, even if there are no immediate plans for them. And at supersonic speeds, the actual Kantrowitz effect would indeed apply. A shock would form in front of the vehicle, but unlike in typical scenarios where it would take place, there is nowhere for the air to go, so once again you would see a pressure buildup between the shock and the pod. Depending on the shape of the vehicle and its relative position in the tunnel the shock could take on different shapes as well. But it’s still somewhat questionable whether the use of a compressor is worth it, or whether there are other solutions, like the ones previously mentioned, that are simpler and more performant.

What does this mean for Hyperloop?

Not much. This could be interpreted as a win for Hyperloop systems, as the analysis, prima facie, suggests that the aerodynamics are not a big problem. But I think the aerodynamics of the pod are a relatively unimportant part of the challenges with Hyperloop, although this facet has received a disproportionate amount of attention from the media (likely due to Musk’s unconventional solution of using a compressor, unlike the other aspects of the concept which have been proposed for a long time already).

But make no mistake, there are many other hurdles—technical, practical, economical and political—that need to be cleared to make Hyperloop a reality. Other people have already covered this to death, so I won’t go into more detail here.

Why did they call it the Kantrowitz limit?

Everything we’ve seen would suggest that what Musk calls the Kantrowitz limit is really just the area-Mach number relation, and to my knowledge there isn’t a special name for it. Kantrowitz certainly doesn’t think he came up with it, since he just mentions it offhandedly in the appendix of his paper, where he simply calls it the “isentropic area-contraction ratio”.

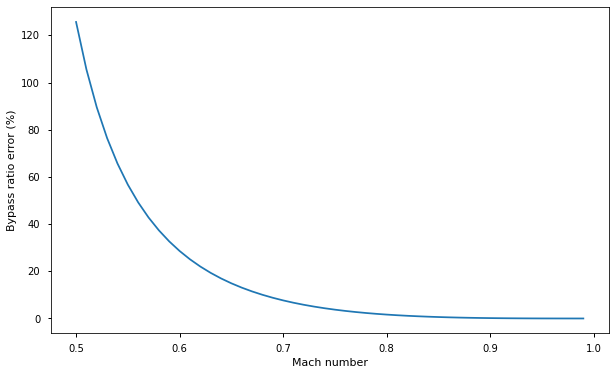

So why did Musk call it the Kantrowitz limit? To be honest, I’m not sure… One could try to argue that the formation of the shock wave behind the choke point is reminiscent of the stable configuration described by Kantrowitz and Donaldson, but it’s pretty clear from reading the paper that this isn’t really what they were concerned about. And naively applying the Kantrowitz limit equation to subsonic systems will get you into trouble—as this graph shows, it results in an underestimation of the true bypass ratio needed… but these values are physically meaningless, since you can’t have a shock at subsonic velocities!

But with that said, if there is a distinction to make here, it’s a mostly pedantic one. From quickly skimming a few of these papers, I don’t think any serious engineers or scientists made this mistake. It seems to be a purely nomenclature thing. Here’s a graph from the prior CFD paper on the blockage ratio vs. free-stream Mach number, reproduced side-by-side with just the area-Mach number equations. Their results are correct—they just called it something it ain’t.

So it seems that before 2013, the Kantrowitz limit was a niche phenomenon that applied to supersonic inlet duct design and was used almost exclusively in that context. After Musk published his white paper, everyone has since erroneously ascribed it to the phenomenon of choked flow and it has since been taken up and popularized by everyone else8. It’s a prime example of citogenesis.

Is there a Kantrowitz limit at all?

Technically, yes. So the title is a little bit of a clickbait. But it has a very specific technical meaning—it refers to the maximum unchoked contraction ratio of a duct that is specifically:

- Naively designed

- In a supersonic stream

- Unstarted

It doesn’t seem that these criteria, with perhaps the exception of the first one, apply to Hyperloop. And as we’ve seen, it’s clear that the issues described by the limit likely aren’t issues at all. I am not up-to-date with the latest developments in Hyperloop technology, but other people seem to be reaching the same conclusions: Virgin Hyperloop pods, for example, don’t seem to be doing very much to mitigate the drag from choked flow.

At the very least, it seems that the Wikipedia pages on the Kantrowitz limit and Hyperloop, at the time of writing, have some glaring inaccuracies.

All this, of course, needs to come with several caveats. I haven’t spent that much time looking into current-gen Hyperloop technologies, and I may have missed other people’s solutions to the pod aerodynamics. I’m also not an expert on compressible gas dynamics, so there’s always the possibility that I am mistaken somewhere. If someone has more information than me about this, please get in touch—I’d love to know!

I actually have no idea where this equation comes from. The paper that Wikipedia cites doesn’t have it, and from what I can tell it doesn’t match up with any of the classical equations I am familiar with. My suspicion is that it was incorrectly transcribed from a derivation of the Kantrowitz limit, since it lines up qualitatively. Hopefully it isn’t used for anything serious… ↩︎

I’m not sure what to even make of their claims. The Kantrowitz limit equation is specifically for compressible fluids. Why would they think that we’ve overlooked the fact that gases become compressible at transonic velocities? And what they do mean by supersonic flow “compressing” the gas along the tunnel? Supersonic flows cannot, by definition, compress anything except through shock waves. That seems like something that would be important to mention. Where did they get all these numbers for the compression ratios?! And this is just the beginning of a long list of issues with this page. ↩︎

The theory of aerodynamics and compressible gas dynamics is surprisingly young. The theory of supersonic shock waves was only developed in 1908, and theoretical solutions to fundamental problems such as flow fields over supersonic blunt bodies were still actively being researched until the mid 1960s. Ludwig Prandtl, considered to be the father of aerodynamics, died in 1953 and was still actively performing research. ↩︎

The flow is usually understood to be due to a difference in pressure, but to be pedantic, it is really a difference in free energy. Pressure is just potential kinetic energy. ↩︎

This doesn’t hold for Mach numbers > 5.0, but in many cases is actually a fairly reasonable assumption for speeds below that and will generally get you within +/- 10% of the actual answer. ↩︎

This is not really an apples-to-apples comparison, since aircraft, as previously mentioned, have free-flowing air around them. Transonic aircraft will experience localized shock wave formation which will result in significantly increased drag, which I ballpark to be within the same order of magnitude as in a Hyperloop pod traveling at its choking velocity. ↩︎

There should also be a point where the drag will begin to decrease, as more of the flow becomes supersonic and the boundary layer experiences less disruption. So it’s not like the drag will continue to monotonically increase, either. ↩︎

To be clear, I am only commenting on the phenomenon as opposed to implying any kind of moral culpability on the part of Youtubers. I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect them to do this much digging to get the proper background on a very niche aerodynamics effect. ↩︎