What makes some open-source projects dominate?

The modern world is built on open-source software. It powers critical functionality in our digital and physical infrastructure. Linux is the operating system of choice for a variety of professional applications ranging from web servers to microprocessors. The internet is built on top of open-source tools such as BIND9, OpenSSL, iptables, nginx, and much, much more. It’s what makes it so easy and inexpensive for anyone to set up a website nowadays—imagine if your options were between writing your own networking stack for scratch or paying some company $500 for a “basic” license1.

Clearly, this is very valuable to the world. How valuable exactly? It’s hard to say for sure, but a 2024 Harvard Business School study estimated the economic value of open-source software to be between 4 and 8.8 trillion dollars.

Not only does open-source software enjoy widespread adoption, it often benefits from explicit support from tech companies, ranging from them allowing employees to make contributions to direct financial backing. That’s a dynamic that’s unusual to see in the corporate world. Sure, many organizations have philanthropic programs, but these companies are donating to projects that could make their own (commercial) product offerings less attractive, or even benefit their competitors! Imagine if ExxonMobil was openly and proudly supporting an organization developing cheap solar panels, and giving away the designs for free.

When does open-source succeed, and when does it make sense for private organizations to invest resources into them? My mental model for this is that open-source software projects are, economically speaking, public goods.

While there are many reasons for making a project open-source and many reasons they succeed (or fail), viewing it from the lens of economic incentives suggests that these projects are more likely to see adoption and receive contributions when:

- Development requires a large pool of knowledge: being open-source means anyone with specialized knowledge can examine the specific parts that they are experts in and improve the software.

- There is high complexity and universal benefits: The technical complexity of these programs is too high for any single group to build and maintain. At the same time, everybody benefits from the software being better. So it’s best to pool resources and treat it as a common good, i.e. it’s a non-zero sum cooperative game.

- There is a wide breadth of use-cases: Widespread adoption means more use-cases, edge-cases, bugs, and operational experiences are uncovered, leading to a virtuous cycle of continual refinement that commercial offerings will struggle to match.

In theory, when a program meets these three criteria, open-source development is likely to succeed. Is this true? Let’s look at a flagship example of an open-source project: C++ compilers.

Case study: the LLVM project

Compilers are programs that translate programming languages into other computer languages, notably machine code that can be executed on a processor.

High-end optimizing compilers are some of the most technically sophisticated pieces of software in existence. Building and maintaining one requires:

- Extremely specialized PhD-level knowledge at the cutting edge of mathematical optimization and computer science.

- Excellent project management practices as these programs must be constantly updated to incorporate new language features or to improve performance. The technical complexity of these programs is probably on-par with an industrial megaproject like a superhospital or a metropolitan transport network.

- Excellent software engineering, as these programs need to be highly modular and extensible and must use computing resources efficiently using techniques like multithreading.

- Deep, “in-the-trenches” knowledge of what “structures” are likely to appear in practical programs, to generate good heuristics on what optimization techniques to use.

- Support for a broad range of architectures, platforms, and hardware, each of which essentially represents a distinct product offering.

There’s a massive financial incentive for developing better optimizing compilers. Improving the average optimized performance by a single percentage point can translate to billions of dollars in savings since every program written in the compiler’s target language can benefit from it.

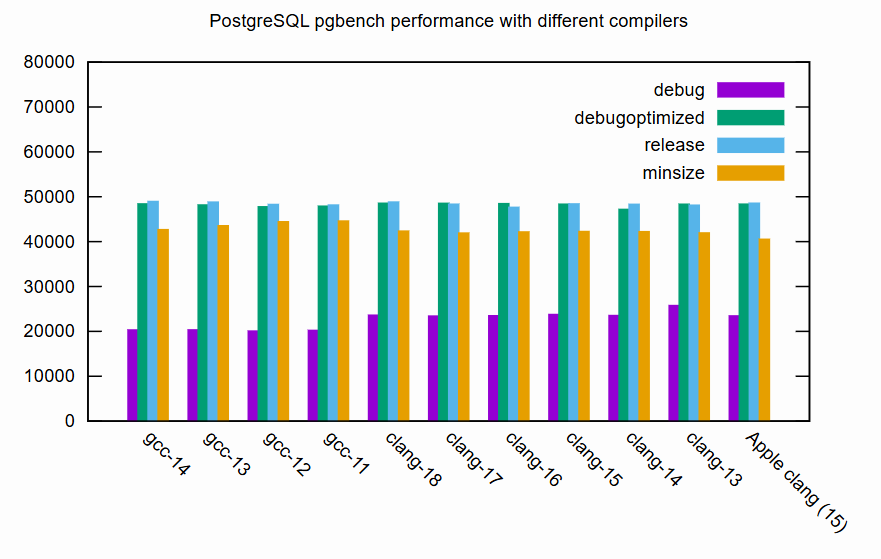

Nonetheless, the two C++ compilers at the forefront in terms of feature set and performance are GCC and Clang/LLVM2. Both of these are open-source projects and are completely free to use. In third place is Microsoft’s MSVC, a commercial and proprietary compiler, and then everything else is a distant last place. GCC and Clang have by far the most extensive feature sets, and most performance benchmarks these days don’t even bother comparing anything besides GCC and Clang (and occasionally MSVC on Windows) because nothing else even comes close3.

Notably, LLVM has several corporate backers, most notably Apple, who hired the project founder, Chris Lattner, and funded the core development team for many years (and continue to do so).

Why did open-source software win here? If we look at the reasons listed previously, it seems that compilers meet all the criteria:

- PhDs in compiler design can contribute to LLVM without having formal ties to any particular organization.

- Everyone benefits from a better compiler, but it’s not a core product offering for most big tech companies.

- Everyone using the compiler means bugs, performance regressions, and common use cases are quickly discovered.

Cool beans.

What I’m curious about, then, is why do we have the exact opposite situation in the world of mixed-integer programming (MIP) solvers?

Counter case study: MIP solvers

MIP solvers are used to solve complex real-world resource allocation and cost optimization problems, such as supply chain routing, electricity grid management, manufacturing production planning, fleet scheduling, and much, much more. They see widespread use in large-scale organizations—the vast majority of Fortune 500 companies likely use them somewhere in their technology stack.

At a first glance, the situation seems very similar to compilers:

- Very specialized PhD-level mathematical knowledge is needed to advance the state-of-the-art.

- A large class of optimization problems are computationally intractable with naïve algorithms, so good heuristics are needed to obtain acceptable solutions in many cases.

- Many possible use cases, requiring support for multiple platforms, languages, interfaces, etc.

- Even small incremental improvements to these solvers could result in millions or even billions of dollars in economic savings.

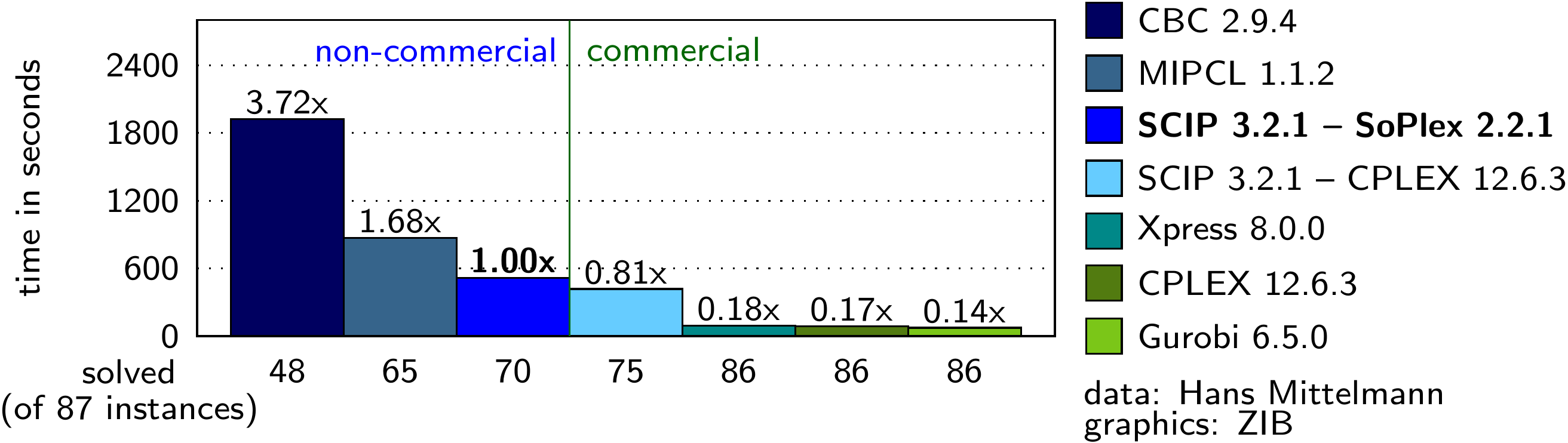

In contrast to the situation with compilers, the leader in this space is generally considered to be Gurobi, which is a closed-source, proprietary solver with a (very very expensive) commercial license. In general, commercial solvers consistently outperform open-source solvers4—they’re orders of magnitude faster for some problems5. There are classes of problems that open-source solvers can’t even solve at all!

Mathematical optimizers isn’t used quite as ubiquitously as C++ compilers, but they’re still commonplace in the modern economy. So why did open-source never take off here? One knowledgeable StackExchange answer lists the following reasons:

- Developing these solvers requires very specialized knowledge, and there just aren’t enough open-source developers with the necessary skillset.

- Many optimization problems are computationally intractable in the general case, so good heuristics are needed to generate a solution. Working with customers creates institutional knowledge about heuristics are effective for real-world problems.

- A solver needs to support a lot of use-cases, programming language, and interfaces, and there just isn’t the appetite among open-source developers to do this kind of menial work.

But at a superficial level, these seem to be the same reasons behind the success of open-source projects, just with a negative spin! So what’s going on? What led to the differences in outcomes here? And are there any lessons we can take away from it?

Possible reasons for the discrepancy

A “critical mass” of people is required for open-source to succeed.

A minimum number of core contributors are needed to maintain a healthy and vibrant community that encourages outsiders to make contributions, resulting in the aforementioned network effects and virtuous cycles.

This seems plausible. Almost every computer science major is exposed to the basics of compiler theory and language design in a good undergraduate curriculum, and at the very least they’ll be aware of the benefits of better compilers. In contrast, mathematical optimization is a much more niche field, usually showing up in upper-level undergraduate or graduate-level applied mathematics courses as an elective.

Still, this raises some questions: if there’s a critical mass of people needed, what is that number, approximately? Would this change if we encouraged more people to study optimization? Should we, given its economic importance?6

Solutions for many use cases are already “good enough”

There are certain classes of problems that can be solved in a provably optimal way. If this is the case for you, and existing solvers already work in a reasonable amount of time, then there isn’t much incentive for further improvement. If this is the case for most users then from their perspective there’s no need to allocate any resources for further development.

But there’s a few issues with this thesis: the vast majority of problems don’t have provably optimal solutions, and if there wasn’t a demand for better solvers, why are there so many commercial options? Doesn’t this imply that users are looking for something better than the open-source solvers, and willing to shell out for it?

Differences in social dynamics

Perhaps there are specific quirks in the way LLVM is managed that made it more enjoyable to contribute to. Maybe all of the open-source solvers are run by cliques that make the experience for outside contributors unpleasant?7

I’m skeptical. While this could be true for a few projects, it seems unlikely that every project suffers from this. Furthermore, this problem should be self-correcting: it would just take one project not run by insufferable assholes and over time all external contributors would flock to them from word of mouth. And from a quick skim of pull requests for HiGHS, they seem like nice enough folks!

Sociological inertia

Most of the main open-source solvers originated from academic projects, which could have resulted in a fragmented ecosystem and insufficient resources devoted to any specific project—if you’re seeking academic brownie points, you’d rather develop your own solver rather than make incremental improvements to someone else’s.

Alternatively, most companies using MIP solvers don’t have a tradition and culture of contributing to open-source code, and so they simply don’t. If you’re an executive at McDonald’s, would you see the benefit in paying well-compensated software engineers and math PhDs to work on something that’s given away for free? A sufficiently dedicated person might be able to make a convincing case for it, but it would take a lot of internal advocacy and persistence to see it through. Is there anyone willing to stake their career and reputation for… a better MIP solver?

In this case, open-source dominance simply hasn’t happened because, similarly to the first point, there isn’t enough momentum behind a single project for everyone to get behind. I don’t have any numbers or statistics to cite here, but I think this is one of the most likely explanations. I’ve seen this dynamic play out many times—nobody wants to be the first mover. How could we confirm that this is the case? Are there any sociological studies that could be done here?

Seek both improvement and elucidation

The case for better open-source MIP solvers is clear, and I think there’s potential for some real progress if one of these hypotheses could be confirmed. After that, the solutions are relatively straightforward. In the case of hypothesis #4, for example, a few individuals could, with some initiative, form a consortium between companies interested in developing better optimization software.

So that’s a concrete benefit. Perhaps even more salient, though, is an opportunity to better understand the sociological dynamics of open-source software. The investment into open-source projects involved a cultural shift away from viewing these programs as tools and towards seeing them as critical infrastructure worth maintaining despite a direct profit incentive. Clearly, this hasn’t happened everywhere.

Sociological theories on human organization and “praxis” abound, but in the messiness of real life there are few opportunities to test them out. But this represents a relatively clean chance to do so, and allow us to gain a better understanding of what makes these projects succeed, and what makes them fail. What is required for success here? And for the projects that are floundering, what actions are needed to set them on the right path?

The potential upside here is enormous. There could be many more cases like MIP solvers. Open-source software is already contributing trillions to our collective wealth, and finding these answers could result in trillions more being unlocked.

What’s that? You want to code your website in TypeScript instead of JavaScript? That’s only in the ‘Plus’ plan, sorry. And did you want caching on your server, too? ↩︎

GCC was the top dog for a long time, but in recent years Clang has pretty much tied it and is even pulling ahead for certain workloads. ↩︎

There’s not much improvement across different compiler versions here, but the pgbench benchmark likely already benefits from heavy optimization, since database operations are extremely common. ↩︎

In this link, Gurobi, MindOpt, OptVerse, COPT and MOSEK are commercial solvers. ↩︎

You might be wondering why we’re comparing solve time here as opposed to how good the solutions are. Even if a solver is slower, do we really care if it eventually finds the same answer? Unfortunately, MIP problems are NP-complete, so the computational complexity scales exponentially with the size of the problem. That makes solver speed very important, because it can mean the difference between a problem being feasible or not. Otherwise, modelers have to make simplifying assumptions, such as approximating a nonlinear function as a convex function, which can significantly improve the solution time at the expense of less aggressive optimization. ↩︎

There’s a good case to be made for ‘yes’. In the past 20 years, there’s been a 50x speed-up in MILP solvers from algorithmic improvements alone. That’s before hardware improvements are taken into account. Given how crucial solve times are for problem feasibility, that suggests it’s still a ripe research area. ↩︎

To be clear, I’m not implying this is actually the case. ↩︎