The Tower’s Long Shadow

To a rough approximation, the process of humanity’s material enrichment is the large-scale solution of separation problems. A disproportionate amount of a substance’s usefulness is derived from the absence of other substances. Water, to take an obvious example, would be a virtually inexhaustible and abundant resource if we didn’t care about the presence of salt in it.

Mastering the separation of a substance—removing undesirable impurities or extracting it from some larger amalgam—is a necessary first step towards commoditization: the process by which production is massively scaled up and costs plummet. It is commoditization that ultimately allows for materials—and the downstream products that require them—to become accessible to the masses.

Examples here include:

- The Siemens process for producing extremely pure semiconductor-grade silicon.

- The Bayer process for extracting alumina, the precursor to aluminum, from bauxite ore. Before its mass adoption alongside the related Hall-Héroult process, aluminum was one of the rarest metals and was more valuable than gold.

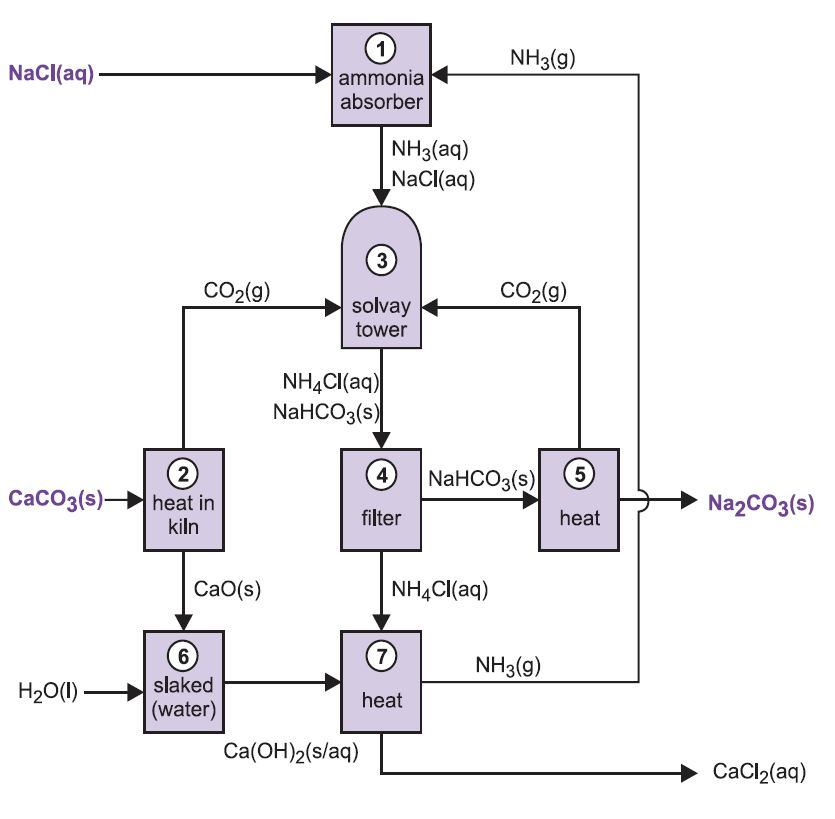

- The Solvay process is the dominant source of soda ash (NaCO3), a key ingredient in glass. It exploits the fact that sodium bicarbonate—the precursor to soda ash—is poorly soluble in water and can easily be separated by filtration.

- Recycling: material sorting, separating plastics from other plastics, precious metal recovery, and so on.

- Wastewater treatment

- Air pollution control: desulfurization or carbon capture as two examples.

- Environmental remediation: extraction of heavy metals, removal of VOCs (volatile organic compounds), treatment of mine tailings.

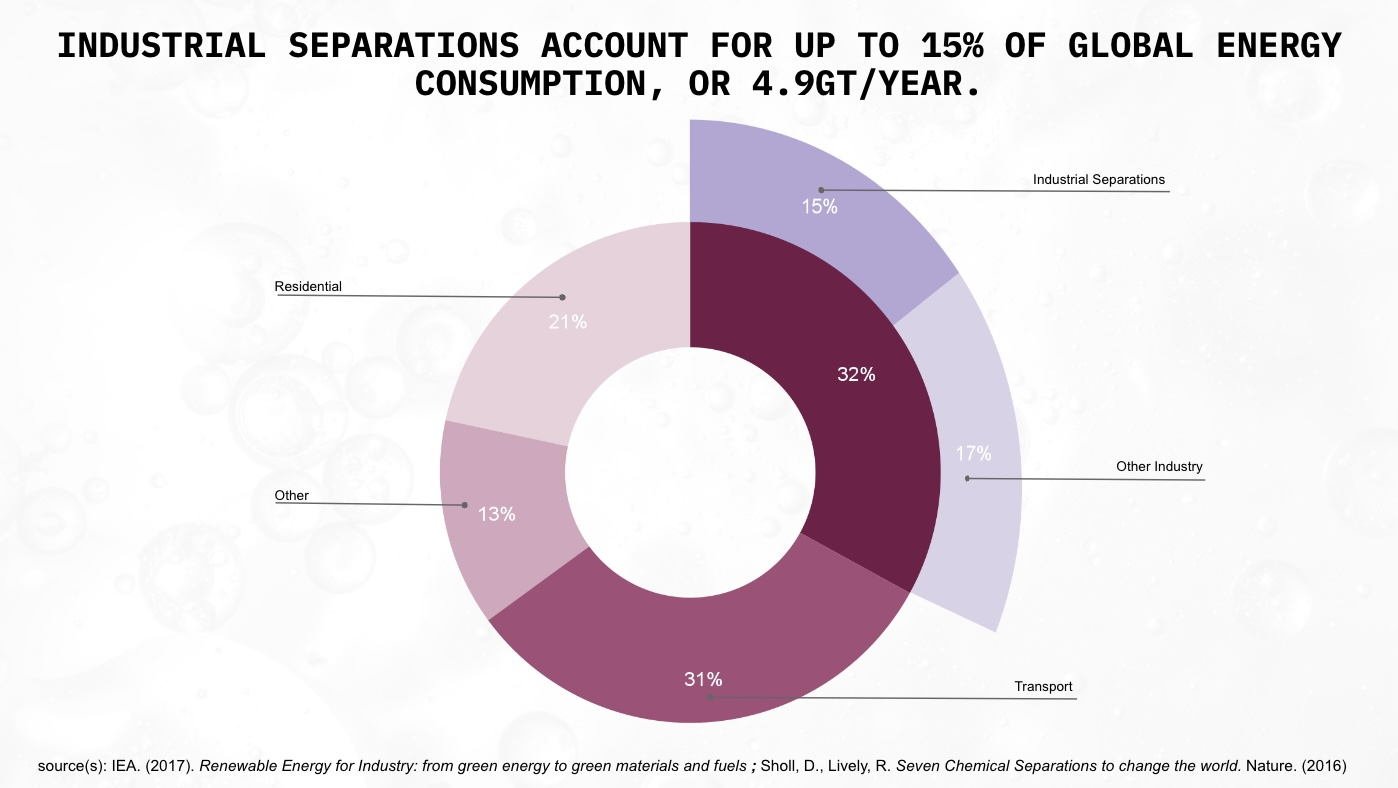

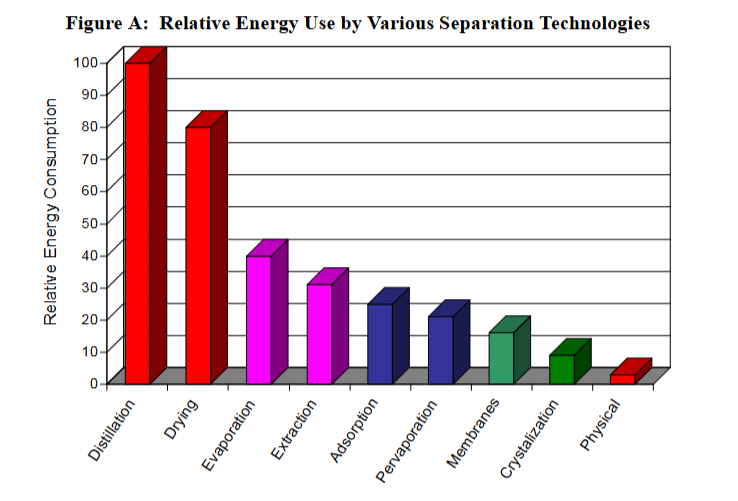

It’s a tricky—and expensive—art. It’s estimated that separation processes account for 40-70% of capital and operating costs in the chemicals industry and 10-15% of all global energy use. The pervasiveness of separation techniques means their difficulty—or lack thereof—drives technological, economic and policy decisions.

A politician may be hesitant to support a new environmental law if it doubles the production cost of gasoline. Their choice could be much easier if it were to increase the cost by cents on the dollar instead. While some people might be strongly inclined to support or reject the proposal no matter the economic costs, it’s the decisions at the margin that end up steering societal outcomes.

It’s no exaggeration to say, then, that separation processes have not only enabled the modern world, they have shaped it—and will continue to shape it.

And among them, there has been one method that stands out from the rest. One that has played a bigger role than any other.

One separation to rule them all.

From the beginning of mankind’s industrial awakening, its fate has been closely intertwined with ours. But there will be a time for us to move on. And that time will come soon.

A towering industry

The most distinctive physical feature of any oil & gas refinery are the enormous metallic towers—often hundreds of feet tall—jutting out of the ground, snaked with piping and access platforms.

At night, they’re pockmarked with bright lights for visibility for maintenance personnel, giving them the appearance of extremely large (and extremely ugly) Christmas trees.

They are distillation towers, used to separate and purify mixtures of liquids, and they’re so ubiquitous that their presence is often synonymous with heavy industry.

Distillation is the most common industrial separation process by a significant margin. It’s estimated that 95% of all fluid-fluid separations are performed using distillation, and that it represents half of all energy consumption for separation (7-8% of all worldwide energy use).

Distillation is the first tool the chemical engineer reaches for when designing new processes; its reputation as the separation process par excellence unchallenged. Here’s what Turton’s Analysis, Synthesis, and Design of Chemical Processes, a staple of the chemical engineering literary canon, has to say:

Use distillation as a first choice for separation of fluids when purity of both products is required.1

It’s hard to argue against that advice. Distillation is a technocrat’s wet dream and beloved by engineers and bean-counters alike.

The scientific principles are well-understood. It has a track record of over a century. It is versatile and works on many different types of chemicals and compositions. Few inputs are needed; mostly a source of heat and a source of cooling. The equipment is simple and cheap to construct. Little maintenance is required. It can be massively scaled up in a predictable manner. It is relatively safe. Few things that can go spectacularly wrong, at least as far as chemical processes go2.

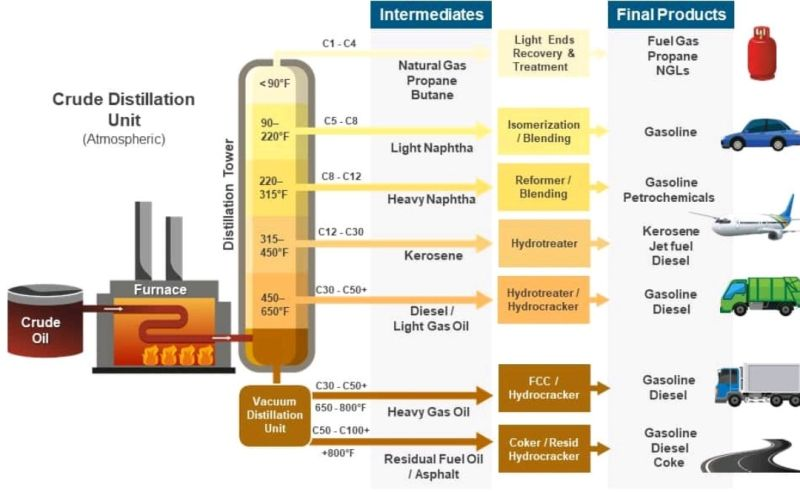

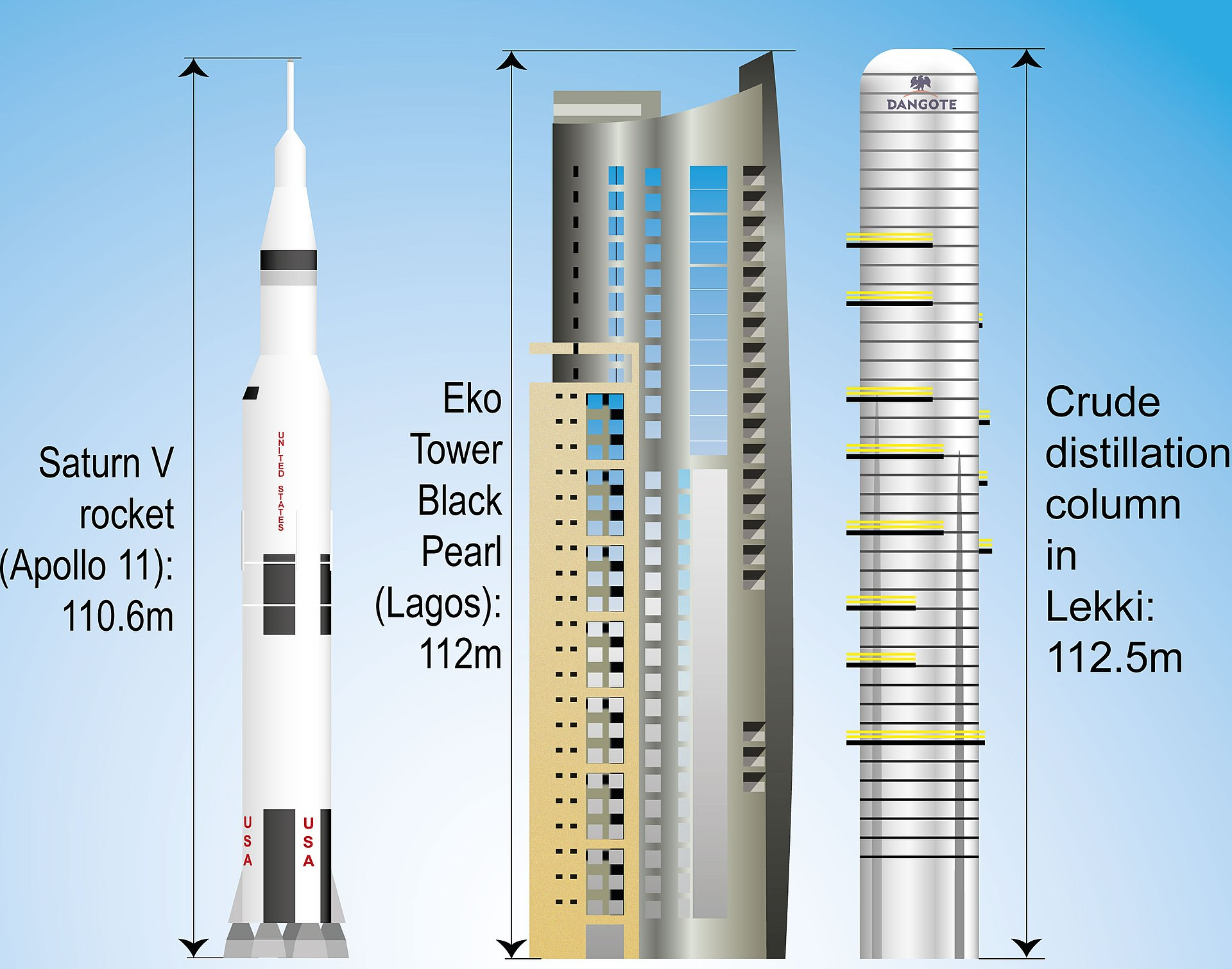

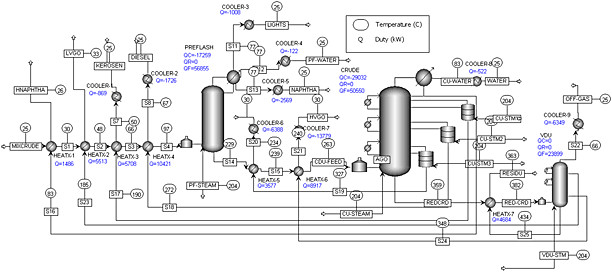

Large-scale distillation columns are astoundingly capital-efficient. The first processing step in any oil refinery is the Crude Distillation Unit (CDU). The centerpiece of a CDU is an enormous fractioning distillation column, where crude oil is split into its different constituents by weight. The entire CDU might have a Total Installed Cost (TIC) of around $1 billion3. Over its useful life, it will process nearly 200 billion gallons—meaning that the capital cost only contributes about half a cent per gallon to the final sale cost of the refined products.

Distillation: a crash course

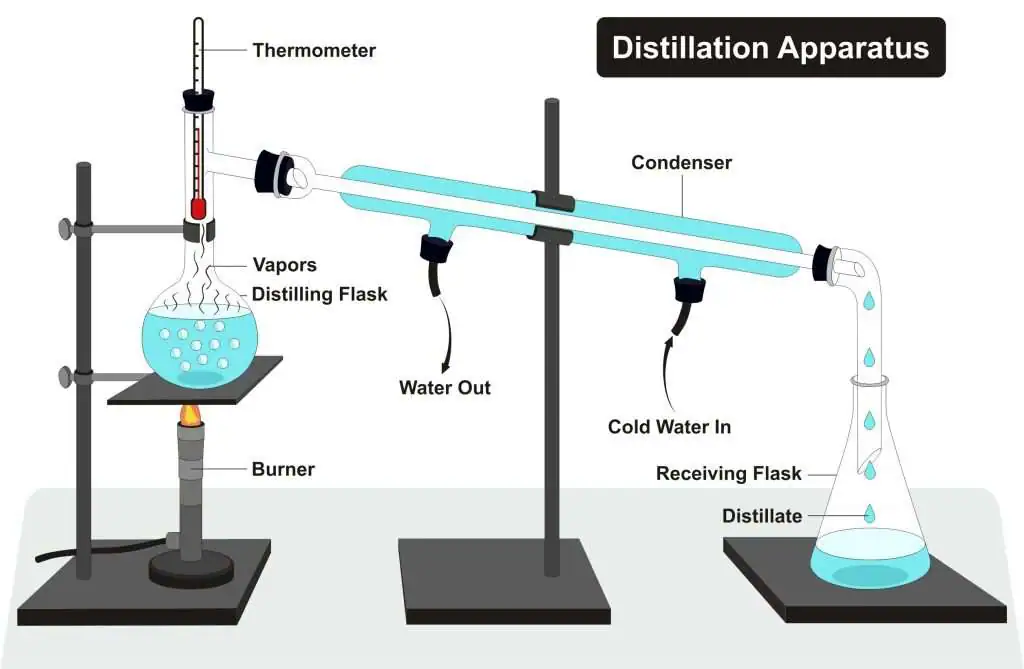

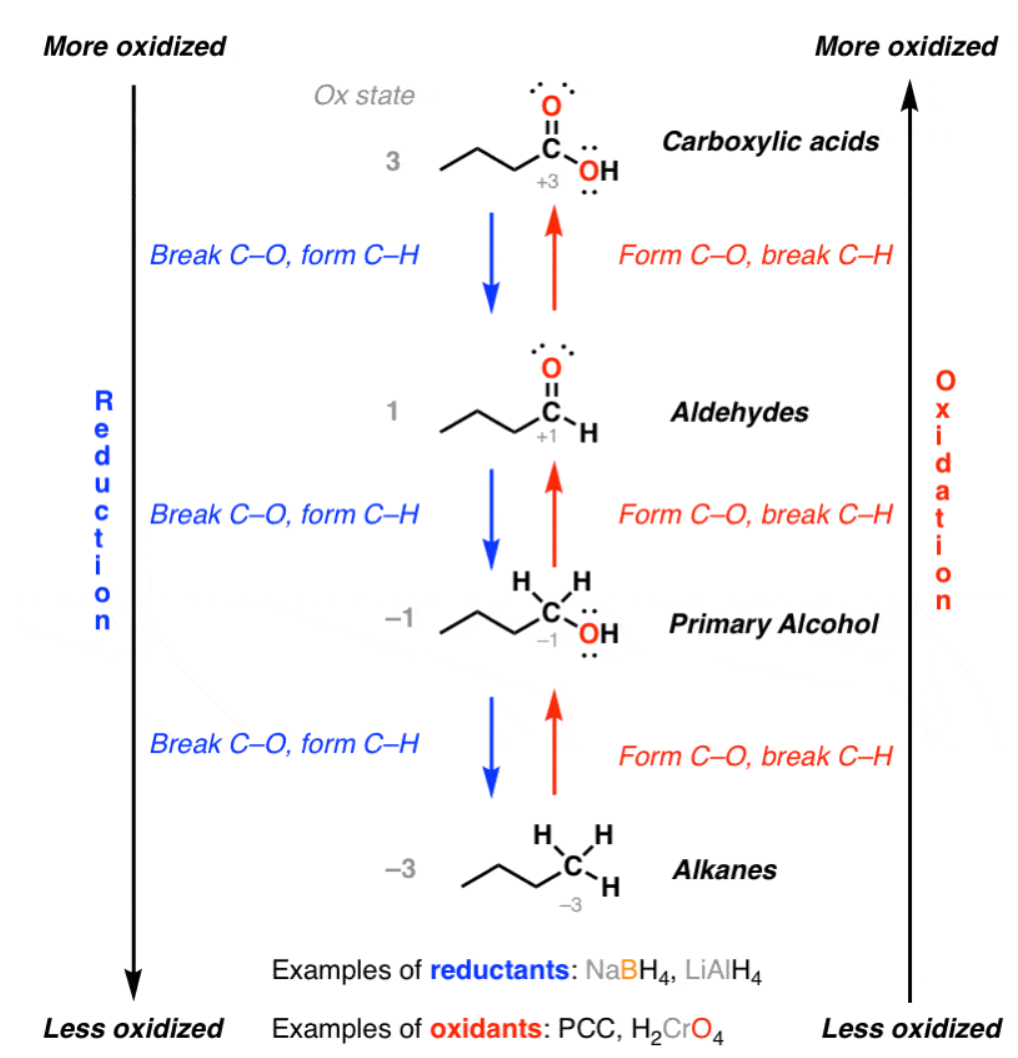

Distillation works by exploiting the differences in relative volatility between different chemicals. Smaller, lighter molecules tend to boil at lower temperatures4. If we have a mixture of different species we want to separate—called the distilland, or the feed—we can heat it to a boil, and then condense the vapors. The resulting product, called the distillate, will be richer in the lighter components5.

Consider the classic case of water and ethanol. Let’s say, for example, that we’re distilling a 50-50 mixture of water and ethanol by weight. Water boils at 100 degrees Celsius, but ethanol boils at a cool 78 degrees. A mixture of ethanol and water will boil somewhere in between—the exact temperature depends on the mixture’s composition.

This begins to boil at around 82°C, rising as the remaining liquid becomes depleted in ethanol. The vapor will be richer in ethanol—75% or more by weight. If we want a higher purity than that, we can simply boil it again after condensing it. This time, it’ll start to boil at just under 80°C, and the vapor will once again be richer in ethanol: around 83% by weight. If we want even higher purities, this process can be repeated until the desired purity is reached6.

Pretty simple stuff. The difference between this and industrial distillation? The sheer scale. Of course, to make it cost-effective, we need to find a way to streamline this process. Boiling the distilland, condensing and collecting the vapors, swapping out the boiling flask and setting everything back up is a pretty inefficient way to go about it. On top of that, bringing the liquid up to temperature and vaporizing it on every distillation pass requires a lot of energy.

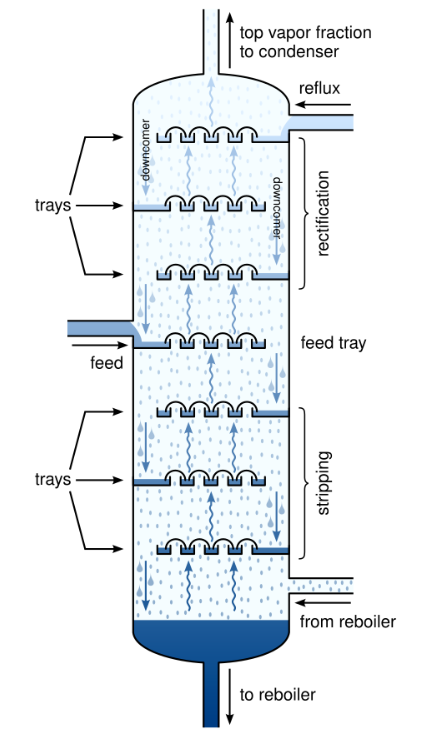

A modern distillation column solves these issues with stunning elegance. It relies on three principles:

- Hotter gasses will tend to rise.

- Vapors have the same temperature as the liquid they boiled off from.

- Mixtures that are richer in light components have lower boiling points.

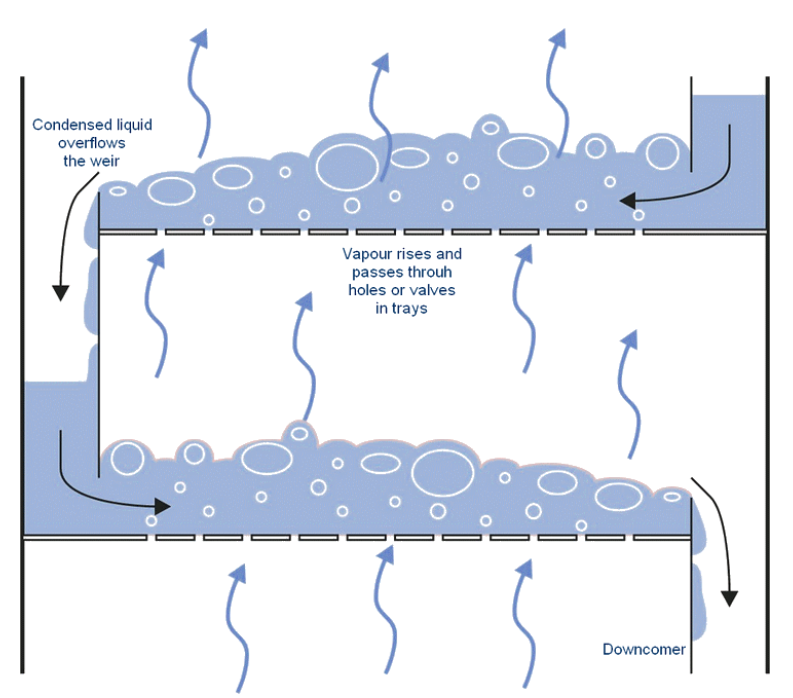

Here’s the idea: take the condensed distillate from the first “pass” and put it on a sieved tray above the distilland. Size the holes in the tray such that they’re too small for the liquid to drip in significant amounts while being large enough to allow the vapor to “bubble through” from below.

The rising vapor is hotter than the boiling point of the condensate. As it bubbles through, it exchanges heat with the liquid, condensing it while simultaneously boiling the liquid. Now the vapor above the tray has effectively had two distillation passes!

There’s one complicating factor: to maximize efficiency, we’d like for this setup to operate continuously. We can do that by pumping in the feed mixture at a constant rate, and simultaneously withdrawing liquid from the bottom. But we can’t have stagnant pools in every tray: eventually, all of the light components will boil off, leaving only the heavies. We mitigate this by adding a small weir on each tray and allowing liquid to trickle down to the stage below. This way, the heavies will slowly make their way to the bottom, and composition on each tray remains stable.

Where does the liquid downflow for the topmost tray come from? When the high-purity vapor from the top of the tray is condensed, a portion of it—called the reflux—is returned to the top tray. If all the trays are filled, the reflux causes a cascade of downflows all the way to the bottom of the column7. This “internal circulation” is a major determinant of the column’s efficacy: the higher the rate of circulation, the better the separation and the purer the products.

If this all seems pretty tricky to keep track of, that’s because it is! Crack open an engineering textbook on distillation and you’ll see esoteric terminology like “McCabe-Thiele diagrams”, “MESH balances”, “Murphree efficiency” and “Erbar-Maddox correlations” being thrown about. But the fundamental principle remains the same: boil stuff and collect the vapor, over and over and over, until a desired purity level is reached.

The end result is a masterpiece of integrated design8, with each feature fulfilling multiple roles and the whole simplified and simplified until, as Saint-Exupéry would say, “there is nothing left to take away”.

Each tray acts as a condenser for the tray below and a boiler for the tray above, requiring no additional heating or cooling. The column’s temperature gradient—hottest at the bottom, coldest at the top—passively establishes itself due to thermodynamics. Thanks to buoyancy effects, the vapors and liquids go where they have to be, without any need for pumps, compressors, fans, or any moving parts whatsoever. The tower’s components are simple, modular, easy to fabricate and amenable to mass production.

Best of all: in terms of scaling, the sky’s the limit—literally. Want a higher purity? Simply add another tray above the first one. Want a higher throughput? Just make the trays wider. While there are obviously practical restrictions on tower size, we can reach astonishing scales and production capacities.

The largest crude distillation unit is found in the Dangote refinery, in Lekki, Nigeria, and is capable of processing 650,000 barrels of oil per day. To put that into perspective, only two of these columns would be needed to process all the oil consumed by the United Kingdom!

Of course, as impressive as this might all be, it doesn’t explain why distillation is so ubiquitous. For that, we need to also examine its role in the chemical production chain. That requires an understanding of the operational constraints and considerations driving the design of oil refineries and chemical plants.

Principles for Petroleum-Plentiful Processes

While a complete overview of the intricacies of refinery design can’t be covered in a single article (or even fifty), I think the dominant design “paradigm” can be summarized with the following three points:

- Heat is everywhere.

- Ensure everything runs, all the time.

- Separation quality is secondary to throughput.

Heat is everywhere

In chemistry terms, petroleum feedstocks are highly reduced: their carbon atoms have a very high electron density and their atomic bonds contain a lot of energy. (That’s why oil is so useful, after all!) There’s a lot of free energy9 available, which means they can be combusted as fuel, but more generally, free energy is what allows things to happen.

And thermodynamically speaking, a lot of things happening means a lot of heat is being produced. Fuel products can be combusted with oxygen to produce lots of heat, but they can also be oxidized to produce more valuable chemicals—such as ethylene glycol from ethylene or formaldehyde from methanol—which also produces heat.

Of course, heat only flows from hot to cold, so higher-temperature needs must be prioritized. For example, if you have steam at 600°C and you need to heat two 100°C streams to 200°C and 500°C, respectively, you should heat the 500°C stream first. Doing it in the opposite order might be impossible, if the 200°C stream cools the steam to below 500°C10.

Many thermochemical reactions require high temperatures to work, often in excess of 500°C. Some, like steam reforming or the reverse water-gas shift reaction, can require significantly higher temperatures even exceeding 1000°C. In contrast, distillation can usually make do with lower temperatures. The CDU is typically one of the hottest columns and operates between 300-400°C. Other columns can operate at lower temperatures than that. That means that distillation can often be powered with the “leftovers” of other processes—which are in plentiful supply.

Ensure everything runs, all the time

The heavily integrated nature of an oil refinery—heat being shuttled to and fro, products moving from one vessel to the next—creates many interdependencies between all the units. This makes reliability and steady throughput essential for safe operation as the refinery’s ability to run at a reduced capacity, is greatly limited. For example, running one reactor at 50% capacity might mean you aren’t producing enough heat to keep another process online, which means all of the downstream operations would be impacted, and so on.

As a result, most refineries typically have a “turndown rate”, or minimum operating capacity, of 60 to 70%. Any lower, and the equipment begins to dip into operating conditions it wasn’t designed for. They’re essentially running near full throttle all of the time. Start-up and shutdown of a refinery is an arduous, incredibly complex and dangerous operation, and it can take weeks or even months before stable operation is achieved. Barring an emergency scenario, a complete plant shutdown usually only occurs once every 5 years or more, during maintenance turnarounds.

Separation quality is secondary to throughput

There are two metrics to characterize the quality of a separation: selectivity, and recovery.

- Selectivity is a measure of how good a separation is at excluding undesirable species. For example, a process that produces 99% ethanol from a 50% mixture is more selective than one that produces 90% ethanol.

- Recovery is a measure of how much of the desirable substances end up in the “pure” output. Starting from 100 kg of 50% ethanol, a process that outputs 50 kg of 99% ethanol has a higher recovery than one that outputs 1 kg of 99% ethanol, even if they have the same selectivity.

- One does not imply the other. It’s possible to have high selectivity with low recovery, and vice-versa.

What quality should we aim for? As commonly the case for any engineering question, the answer is “it depends”. Higher selectivity and recovery, all things equal, will cost more, so we should aim to have a separation as good as the product needs—and no more.

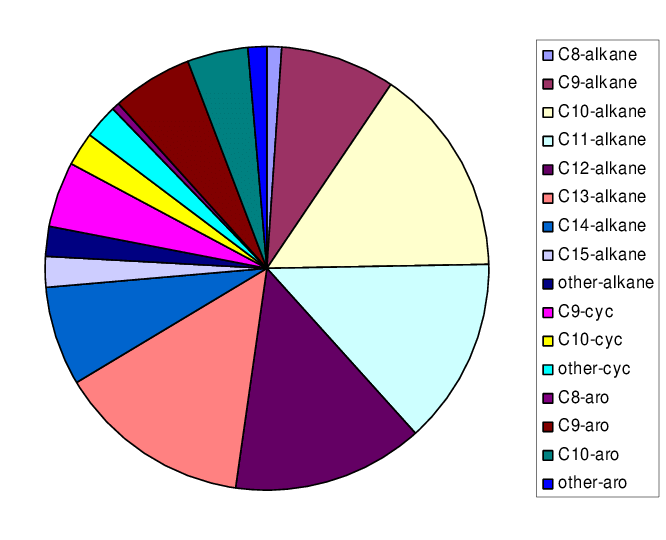

How good does the product need to be? About 85% of a crude barrel of oil is subsequently used as fuel, rather than to make plastics or other chemicals. Fuel products such as gasoline, diesel or kerosene aren’t any single molecule, but a collection of dozens or hundreds of different molecules that as an ensemble have bulk properties—viscosity, melting point, vapor pressure and density, to name a few—that allow them to be classified as, well, gasoline, diesel or kerosene. These classifications are all maintained by big standards organizations, like ISO, to ensure cross-compatibility. This ensures that gasoline adhering to ASTM D4814, for example, will work in every engine that runs off of gasoline.

That means there’s little value-add from achieving high recovery or selectivity11, and if the product meets spec, it’s good enough. Going beyond that is the equivalent of the snotty teacher’s pet asking for more homework. (Don’t do it.)12

The way to increase your profits, then, is to make more fuel. And this favors separation processes that are very large-scale, even if they aren’t the most performant.

To summarize: in a petrochemical plant or refinery, the feedstocks contain a lot of energy → a lot of heat is produced → the plant operations are heavily interdependent → the plant needs to run at full capacity everywhere.

Furthermore, because the value of fuel products is from burning them, separation performance is less important than just producing as much fuel as possible. Under these circumstances, distillation is truly the perfect fit. There is no better tool available as a versatile and reliable separation workhorse.

But as we sing its praises, we also have to acknowledge its shortcomings. And it is these shortcomings that threaten its status as the separation process par excellence.

The trials ahead

So, we’ve all agreed: distillation is great. But spend any time reading contemporary industry or academic articles on separation science and you’ll frequently encounter discussions on getting rid of it. Why?

As the world undergoes an unprecedented energy transition enabled by new technologies and accelerated by new imperatives, and as the environmental impacts of our activities are increasingly better-understood, it’s clear that distillation is fundamentally ill-suited for the challenges ahead.

Future separations will be more demanding

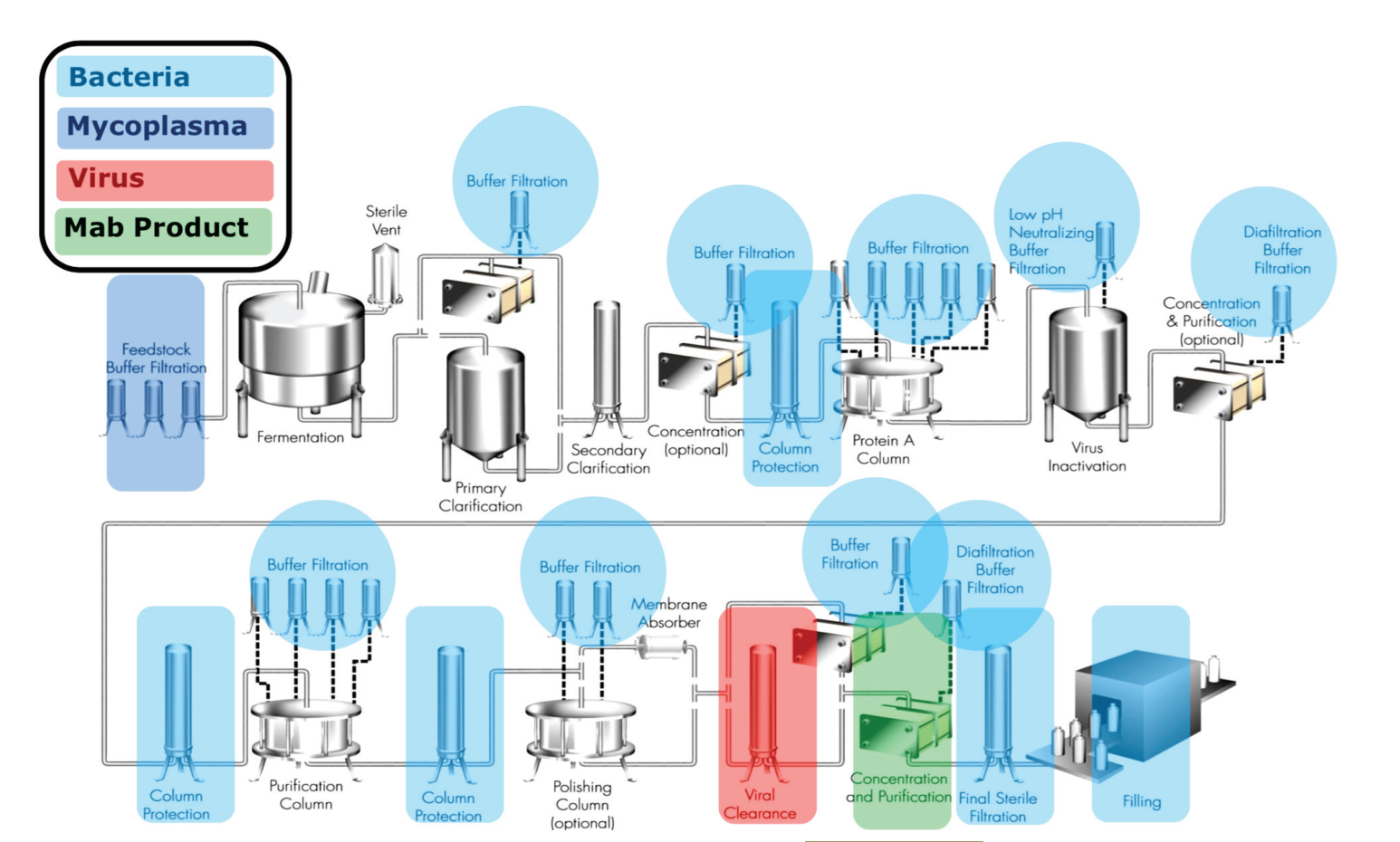

Any description of all “future separations” is going be painting with a very broad brush. However, from examining industries that are expected to become more prominent in the coming decades—biotech, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and waste recovery—we can make some inferences. The next set of challenges will predominantly involve:

- removal of solids, e.g. PFAS and microplastics removal.

- separation and concentration of ions13, e.g. desalination, industrial wastewater treatment.

- high selectivity and recovery, e.g. monoclonal antibodies.

- separation of trace compounds, e.g. extraction of uranium from seawater, environmental cleanup.

These are all situations where distillation is ill-suited; it would have very poor performance or it wouldn’t work at all.

Energy efficiency matters now

Unlike petroleum feedstocks that are primarily reduced, future separation problems will be working with molecules that are primarily oxidized. They won’t have as much excess energy to go around, and any energy deficit will need to come from some other source, such as electricity. The implications are severe.

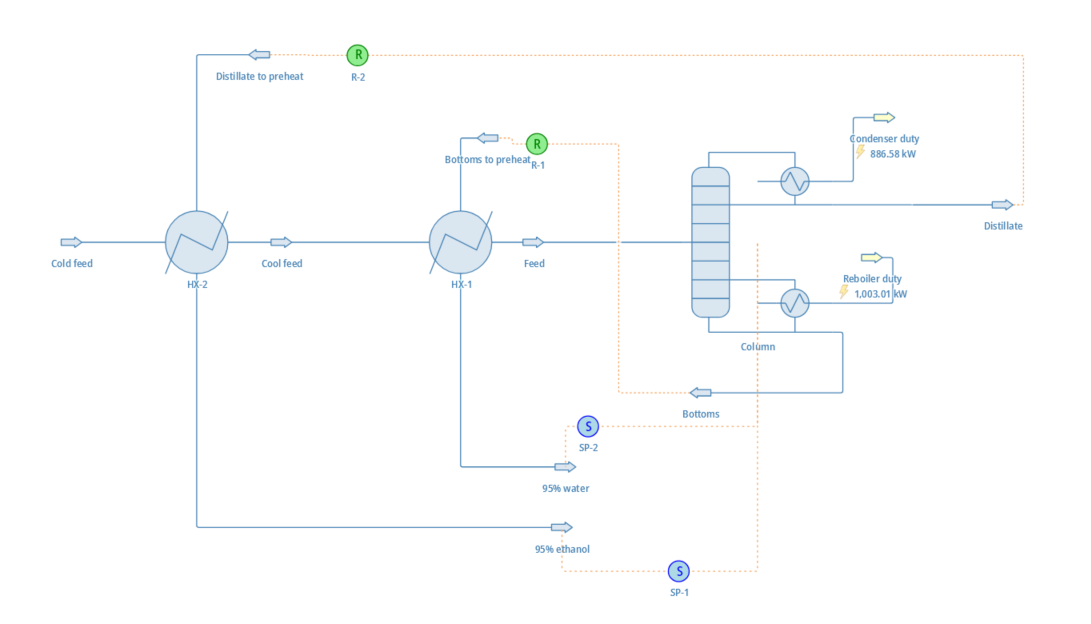

Let’s return to our original example of 50% water and ethanol. Let’s say that we want to to separate it into two higher-purity mixtures: one being 95% ethanol, and the other 95% water. Crunching the numbers, we discover the following:

- Doing this with a typical distillation column would require around 1 kilogram of reflux per kilogram of distillate, and 11 stages.

- The minimum theoretical energy required to perform this separation is surprisingly low: only about 15 kilojoules per kilogram. In comparison, combusting one kilogram of the 95% ethanol mixture would generate over 29,600 kilojoules of heat!

- Distillation requires significantly more energy than that: if powered electrically, the boiler would require around 1,000 kJ per kilogram.

- Even if we assume all of the energy used to operate the condenser is “free”, the energy efficiency is a dismal 1.4%.

Boiling liquids takes a lot of energy. Distillation is, by a large margin, the least energy-efficient separation process. Even in extremely well-optimized scenarios, it’s a challenge to reach efficiencies over 10%.

This isn’t a big deal when there’s a local supply of use-it-or-lose-it heat14, but when lunch is no longer free, these inefficiencies really begin to bite. To improve on these numbers, new approaches will need to rely on different separation mechanisms that don’t involve vaporizing liquids.

Dynamic operation will become more common

The electrification of industry alongside a deepening penetration of renewable energy on the grid will present new challenges and new opportunities. As intermittent energy sources like wind and solar become more prominent, dispatchability will command a premium on the supply side, and equally on the demand side.

Demand response strategies can result in significant cost savings for industrial customers by allowing them to consume electricity only when it’s abundantly produced. Electricity from solar and wind at the right time can be extremely cheap since the marginal cost of production is nearly zero.

Doing this, however, requires the ability to rapidly ramp production up and down. And unfortunately, distillation columns don’t like change. They especially don’t like fast change. Getting them going from a “cold” start is a slow process. It takes several hours to warm up all that liquid and metal, even with the reboiler running at full power.

Beyond the issues with starting up, they generally don’t take too well to a variations in throughput. Columns are designed for specific operational conditions and circulation rates, and dropping outside of the “happy” range will quickly result in operational issues, such as tray flooding or weeping, which will crater the separation performance and result in off-spec products.

Depending on how the column is integrated into the plant, the consequences of this can vary wildly. If the distillation tower is at the end of the production chain, then it may simply result in a lower-quality product that must be sold at a lower price.

At the other end of the spectrum, a misbehaving fractionating column at the heart of the refinery can quickly spell disaster if not immediately addressed. Products will end up in places they aren’t intended to be; undesirable impurities can deactivate catalysts or contaminate products, unexpectedly high volatilities can cause equipment overpressures, and overly viscous fluids can gum up pumps, pipes, and foul heat exchangers. In the absolute worst-case, this leads to a series of cascading alarms and failures that eventually brings down the entire plant.

This isn’t to say that these issues are impossible to solve. But they’re very difficult, and non-thermal processes that rely on other driving forces, such as pressure, have a much easier time adjusting their output.

Why haven’t other techniques taken over yet?

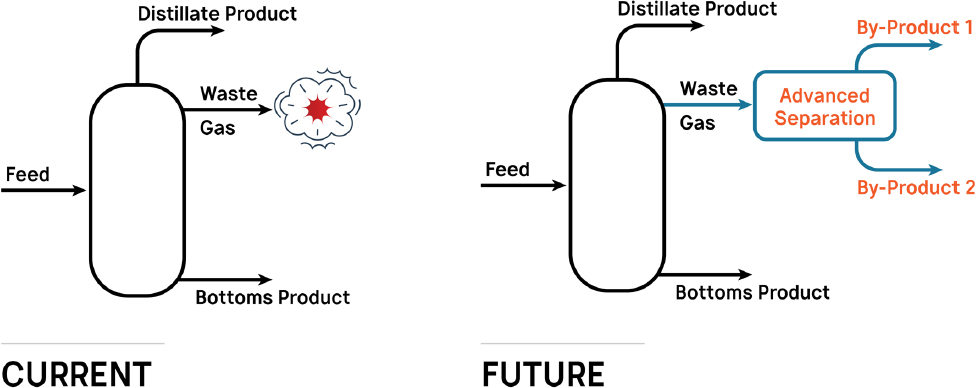

None of this is a surprise for those who work in the industry. The need to move away from distillation has been well-recognized for decades. And we have a pretty good idea on what should replace it: primarily electrochemical and membrane-based techniques.

These technologies will be significantly more energy-efficient and will be able to operate much more flexibly. In many cases, the energy savings can be orders of magnitude. Remember our 50% water-ethanol mixture? A carbon membrane-based reverse osmosis system could require only ~25 kilojoules to separate it—at least a 40x reduction in energy consumption15.

There’s no shortage of promising ideas. Redox-active adsorbents for ion separation. Carbon nanotube membranes for precise molecular filtration. Bipolar membrane electrodialysis for organic acid regeneration (and many other applications). Ionic liquids for extracting biological compounds.

But progress has been slow. Innovation in the physical world of atoms is extremely difficult in the best of cases. But for chemical process technologies, the innovation valley of death becomes a canyon. A perfect combination of economic and technical factors conspires to make it nearly impossible.

The capital requirements for chemical plants are immense; even small projects can require hundreds of millions of dollars in investment. Furthermore, the cost structure is heavily front-loaded: it’s estimated that 80% of a chemical plant’s production cost is determined by the time the preliminary design is done. A move-fast-and-break-things approach, as is frequently used in the software industry, is simply not a viable strategy.

This makes the people who fund these projects extremely risk-averse, particularly towards technological risk. These plants are expected to last decades, and even when the technology is mature, the inevitable risk of budget and schedule overruns as well as shifts in the macroeconomic environment can quickly financially sink a project. Why would you want to run the risk of the plant not even working at all?

Along a similar vein, most process equipment is expected to last decades, and problems may only manifest years after commencement of operations—which can itself be many years after the project is greenlighted. The result is an anemic feedback loop for designs, making iterative improvements and learning-by-doing challenging.

There is another factor worth discussing, and it’s the most insidious one of them all.

In 2019, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) published A Research Agenda for Transforming Separation Science, a “Consensus Study Report” containing detailed recommendations regarding future research directions and educational curricula in separation science. These peer-reviewed reports are reflective of the expert consensus around a topic, and while NASEM isn’t a policymaking body, its reputation means that its stances hold considerable weight.

What was surprising about this particular one was the emphasis on needing advances in fundamental theory while simultaneously lamenting the perception of the field among researchers as outdated and uninteresting.

On the need for better theories and models:

The vision […] of unification of the general principles of separation science has not been achieved. Chemists and chemical engineers engaging in separation science and technology do not even speak a common language.

[…]

Accurate models for predicting binary and multicomponent behavior from data on single components […] do not exist for most types of separation materials.

And on the perception of the field:

… numbers of faculty members readily identifiable as separation researchers have decreased by 40% in the top chemistry departments and by 30% in the top chemical engineering departments since [1987].

[…]

Graduate students view separations as old-fashioned. None of the top 20 chemistry or chemical-engineering programs list “separations” as one of their topical research areas.

These are startling admissions. How can a field still have fundamental theories left to be discovered, yet at the same time be derided as boring and unfruitful for research?

While we’ll never truly pin down the root causes of this, we can indulge in some speculation. Speaking from experience, models for predicting separation behavior for many materials are indeed lacking. It’s all an inconsistent patchwork of different applicable ranges, concentrations and compounds, and you’ll have to dig through a bunch of experimental papers to find data, if you’re lucky.

There is, however, one notable exception.

An abundance of ready-to-use models for predicting vapor-liquid equilibria, and a long history of theory development in this subfield.

Technological development is path-dependent. New innovations don’t come out of thin air: they’re developed in response and in the context of the things that came before.

And in this context, distillation’s dominance in petrochemicals came at the price of choking out the development of other separation technologies—like a grandiose, towering redwood whose shade has prevented smaller trees from receiving enough sunlight to thrive.

What was lost isn’t something that can be directly observed. It is seen from what isn’t seen. It’s the paths never taken. The research never explored. The ventures that quietly went under. The intimate process knowledge never gained. The lack of opportunities. The people who leave the field. And the people who never enter in the first place.

Once a plant stops receiving enough sunlight, it begins to stagnate. Its growth becomes stunted. If the deprivation goes on long enough, it’ll begin to shrink, wither and eventually die.

This might all sound very gloomy and discouraging, but I think it’s actually very exciting. The winds are beginning to blow in the opposite direction. There are vast uncharted territories in separation science, and mapping out even small sections could have a huge impact. There’s opportunities not just for nose-to-the-grindstone practitioners and experimentalists, but also for more high-minded theoreticians.

These advances will rapidly compound off of each other, leading to a virtuous cycle of improvements, new applications, and new separations. How many useful separations aren’t done right now because they aren’t economically viable?

For example, the commercial success of desalination with reverse osmosis membranes are spilling over into other disciplines, even if the former is beginning to stagnate. The process technology is now well-understood and there now exists significant engineering expertise on how to design these systems. New technologies, such as Via Separations and their graphene oxide membranes, are now able to piggyback off of this knowledge to rapidly commercialize new applications16.

And as new, better, more efficient, more specific separations are commercialized, new paradigms in process design will arise, enabling us to produce more, use more, prosper more—while simultaneously allowing us to reduce our impact on the environment. Of course, none of this will be easy. There are decades worth of inertia to overcome, and success is not guaranteed.

Can we do it?

Well, we’re pretty good at boiling stuff.

But I think we can get good at some other things, too.

Other design tips include “Do the easy separations first” and “Do not recombine separated streams.” ↩︎

There sadly still have been some tragic incidents, one of the worst being the 2005 Texas City BP refinery explosion which killed 15 workers and injured another 180. ↩︎

This includes supporting equipment such as fired heaters, accumulators, piping, instrumentation, control systems, heat exchangers, and more. The actual column itself costs significantly less, maybe around $100 million or so. ↩︎

Water is an exception and has an unusually high boiling point for a molecule of its size due to its unique intermolecular interactions. Actually, water is a really weird molecule in general. ↩︎

How much richer? That’s determined by chemical thermodynamics. (This subject is best mentioned in passing and then never brought up again. For my sanity, and yours.) ↩︎

There’s a hiccup here, though: water and ethanol form an azeotrope at a composition around 95.6% ethanol by mass. At this stage, the vapor will have the same composition as the liquid and distillation will no longer work. Fortunately, there are many techniques available to “break” azeotropes. ↩︎

To maintain stable operation, the downflows must be matched with vapor upflows originating from the reboiler. ↩︎

Personally, I think this goes underappreciated even by chemical engineers. ↩︎

“Free” in the thermodynamic sense, although now that I think about it, “free” as in “free beer” works too. ↩︎

The art of optimizing a plant’s heat distribution network to ensure the heat gets used as efficiently as possible is a complex activity called pinch analysis. In a modern plant, a good pinch analysis is practically a requirement to be cost-competitive. ↩︎

Not entirely true. You could, hypothetically, run a bunch of marketing campaigns to get people to buy gasoline with octane ratings that they don’t need. Not that anyone would do such a thing, of course. ↩︎

Seriously, don’t. ↩︎

Although the obvious one here is seawater desalination, a surprising number of critical separations are fundamentally ionic separations. It turns up in unexpected places such as carbon capture. ↩︎

I do want to emphasize this point. As others have pointed out, the “efficiency” of distillation is heavily context-dependent. It can be the most energy-efficient solution if it can use a heat stream that otherwise wouldn’t get used. ↩︎

If anything, this is an underestimate. The actual energy savings would actually be significantly higher as this value is for a complete separation, and because of the azeotrope at around 95.6% ethanol. Separation beyond this purity via distillation considerably more difficult (and energy-intensive), but a membrane-based process can bypass the azeotrope entirely. ↩︎

Their first project was dehydrating black liquor (a byproduct of paper pulp manufacturing), but graphene oxide membranes have many potential applications. ↩︎